Review: A groundbreaking show to confront the gender bias in art: ‘Women of Abstract Expressionism’

Art museums in Los Angeles currently overflow with first-rate exhibitions. An unusually strong array of well-organized solo and thematic shows covering a variety of art has made the first months of 2017 a standout season.

Still, it’s not enough. Something’s missing. A two-hour drive east to the desert reveals what it is.

There one will discover “Women of Abstract Expressionism,” an important show at the Palm Springs Art Museum. On view until May 28, it’s a groundbreaking survey of a dozen artists working in San Francisco and New York from the late 1940s to the early 1960s.

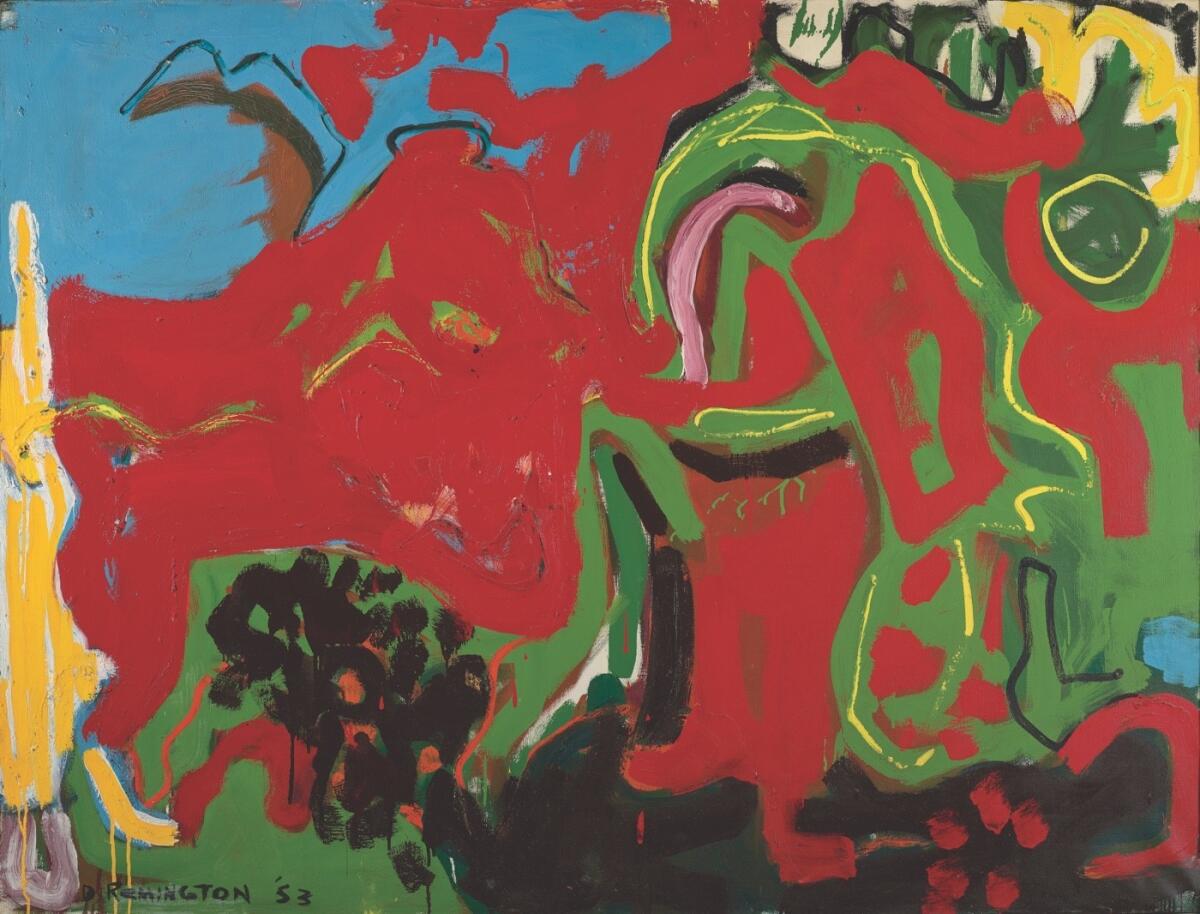

They were instrumental in developing Abstract Expressionist painting, commonly regarded as the first major American art movement after World War II, and a movement dominated by names like Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning. The women range from such top-level artists as Jay DeFeo, Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell to less familiar figures, including Sonia Gechtoff and Deborah Remington, who should be far better known.

It’s the kind of show that can shake up preconceptions.

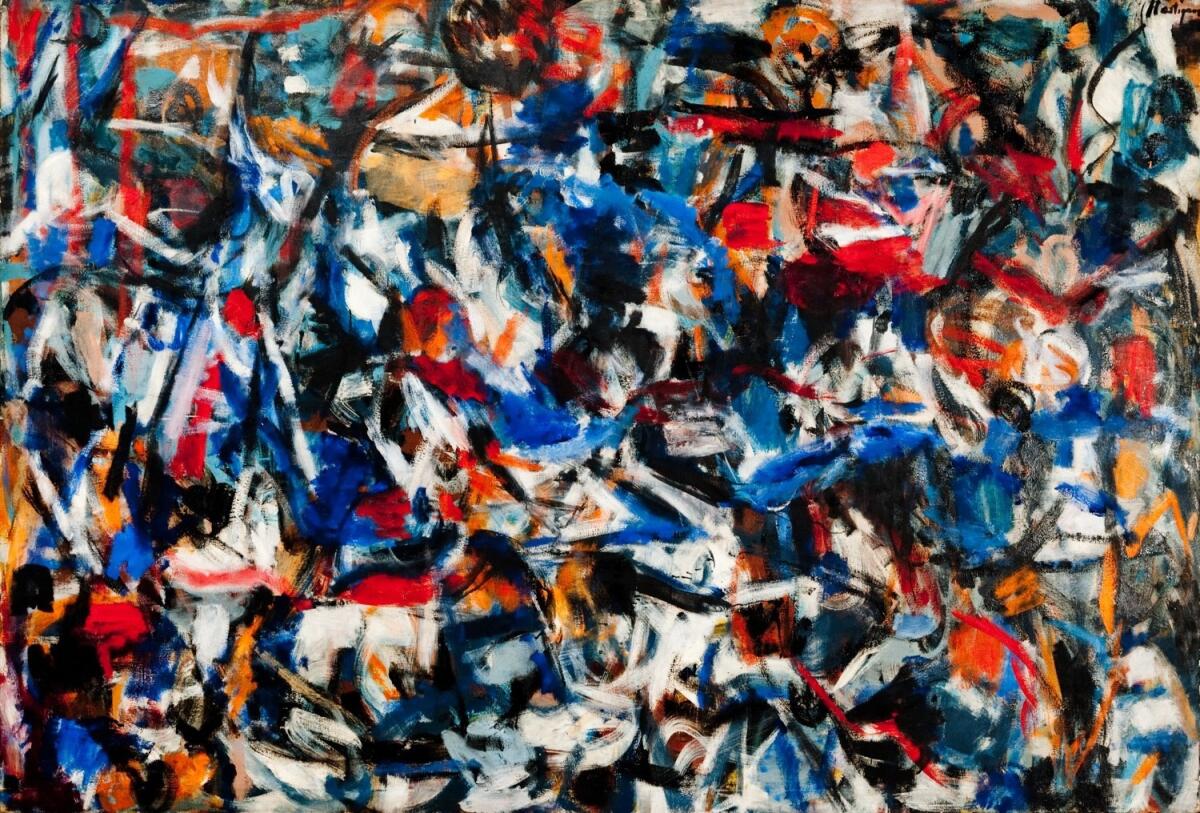

The fat, brashly colored, crashing brushstrokes in the work of Elaine de Kooning (wife of Willem) seem overblown and contrived, as if they are trying too hard for impact. By contrast, “The King Is Dead” — an agitated, all-over field of red, white and blue markings studded with rainbow flickers plus dense black — puts Grace Hartigan at the leading edge (the marvelous painting dates from 1950).

And Ethel Schwabacher, an artist virtually unknown to me, starts out as an adept camp follower of Philip Guston’s misty abstractions, before quickly moving into a strikingly distinctive fusion of shapes and brushwork that seemed carved from explosive color.

Each of the 12 is represented by anywhere from three to six pictures. The catalog includes a useful chronology of the period and several good essays.

As a bonus, it also features short illustrated biographies of 30 additional artists. Denver Art Museum curator Gwen F. Chanzit and Rutgers University art historian Joan Marter considered more than 100 painters for their exhibition, which gives an indication of the breadth of the Ab Ex movement. (Twenty years ago, Marter organized the only other survey of this kind for the City University of New York, featuring just seven women.) Reproductions can mislead, but several of the unexhibited artists would appear to be worth another look.

Meanwhile, here’s the cream of what is on view now in L.A.

The Museum of Contemporary Art has history paintings by Kerry James Marshall and Minimalist sculptures by Carl Andre. The UCLA Hammer Museum is showing Jean Dubuffet’s drawings inspired by outsider art, plus a rare survey of assemblage sculpture by Indian activist Jimmie Durham, an American expatriate.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has geometric abstractions by painter John McLaughlin; varied work by the eclectic and multidisciplinary Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy; paintings by Diego Rivera and Pablo Picasso, friendly rivals in Paris (and beyond); a modest selection of meditative abstract paintings and collages by Iranian artist Y.Z. Kami; and, “Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959-1971,” a sizable overview of the influential avant-garde gallery that began in Westwood and ended in New York, putting Land artists Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer (among others) on the map.

At the Getty, the first survey of sculptures and drawings by the extravagantly talented but nearly forgotten Edme Bouchardon, 18th century court sculptor to Louis XV, just closed. But, if you get my drift, what we have here in L.A. and Palm Springs is a tale of two cities: The gentlemen are ensconced in the megalopolis, occupying prime museum real estate in one of the world’s leading art capitals, while the ladies are visiting a lovely little getaway resort nearby.

I’m happy that all these shows have been done, and happier still that most have been done very well. But that’s a male-to-female museum exhibition ratio of 10 to 1.

The gender distinction might sound harsh, and the current mash-up is just a snapshot in time; yet, it does underscore a degree of ongoing institutional obduracy when it comes to considering the history of art made by women. Organized in Denver, the show has traveled to the Mint Museum in Charlotte, N.C., but it won’t be seen in San Francisco or New York, where the art was made.

Persistent gender issues also demonstrate some of what the “Women of Abstract Expressionism” were up against 60 years ago, as the devastating Second World War ended and most Rosies stopped riveting. Historical group surveys that employ gender as an organizing principle don’t always make artistic sense, but this one does.

The curators propose that these 12 artists, representative of many others, have some things in common. Many paintings are responses to nature, others to literature and music, still others to the vibrancy of urbanism and cloistered domesticity.

Experiments with materials were characteristic — nowhere more than in DeFeo’s monumental “Incision,” a great gray slab of 9-inch-thick oil paint almost 10 feet tall and 5 feet wide and sutured with string, a piece that took almost three years to paint (1958-61). If Ab Ex was in part an effort to identify — and invent — the emotional, spiritual and even physical contours of a self through the demanding process of making art, the boundary-crossing “Incision” is a virtual emblem for it.

In fact, given the shifting role of women in American life in the wake of the war and on the brink of a renewed feminism in the 1960s, what more appropriate movement than Abstract Expressionism — a dauntingly complex phenomenon, especially in painting? Picasso was the deceased royalty being referenced in Hartigan’s “The King Is Dead,” a mural-size tour de force that untangled his brand of Cubist facture and turned it into a whirling dervish of paint-loaded brushwork. A wholesale transformation in avant-garde artistic understanding was unfolding nationally — and quickly.

Perhaps inevitably, the focus soon narrowed to a relatively modest number of men working on the island of Manhattan, center of financial markets and publishing. There’s a sense in the show, astutely commented upon in the catalog, that female artists working in San Francisco faced less of a hurdle than those in New York. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that they faced hurdles, but the obstacles were shared by their male counterparts who also worked in California.

“Women of Abstract Expressionism” is important the way shows of postwar geometric abstraction are. It “de-masculinizes” the practice of painting, much the way the Japanese influence on John McLaughlin, French influence on Ellsworth Kelly and Carmen Herrera and efflorescence of geometric painting in Latin America in the 1950s “de-Americanizes” it. The so-called New York School looks very different as a result of the expanded context.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Women of Abstract Expressionism’

Where: Palm Springs Art Museum, 101 Museum Drive

When: Through May 28; closed Wednesdays

Information: (760) 322-4800, www.psmuseum.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.