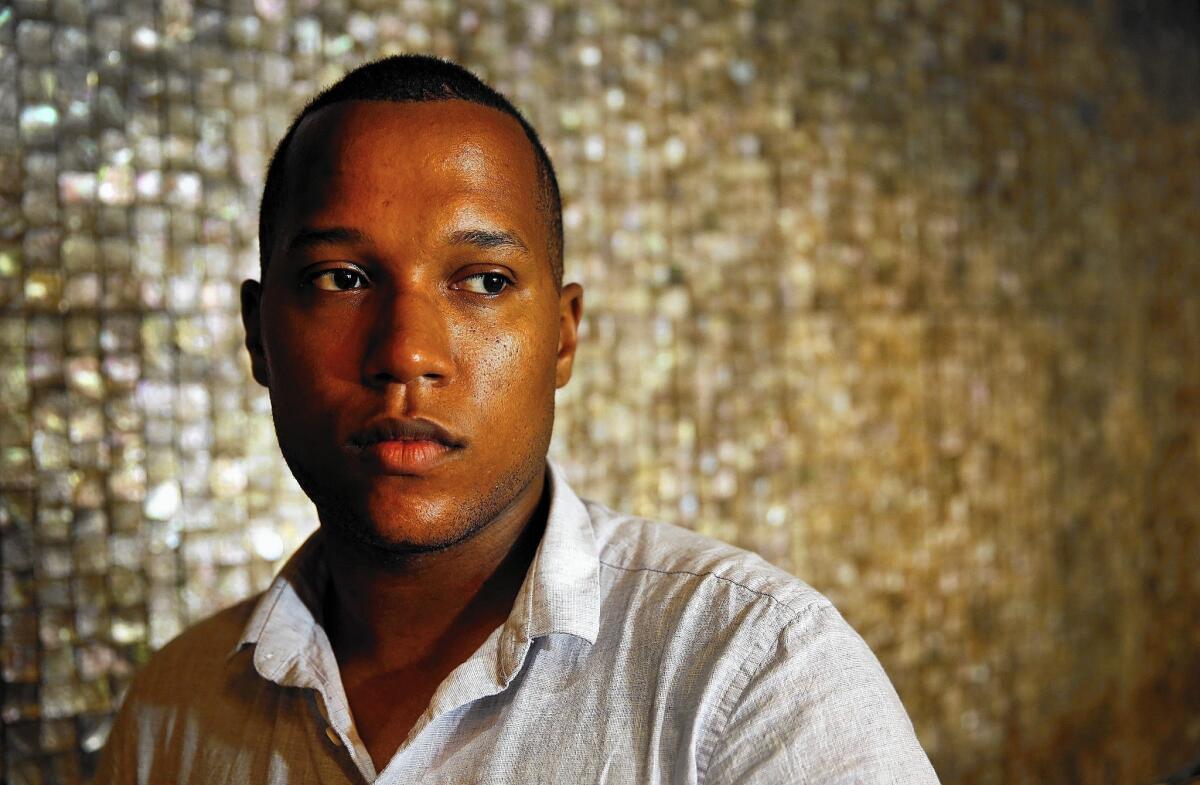

Spotlight shines brighter on ‘Appropriate’ playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

Sometimes being a famous playwright means you have to have dinner twice on a Thursday.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins leaves a rehearsal of his play “Appropriate,” opening Oct. 4 at the Mark Taper Forum, to eat first with a reporter, then later with his agent and some unspecified Hollywood people, who presumably hope to lure him away from the field and city where he has experienced meteoric success in the last five years.

At 30, Jacobs-Jenkins is a bright star in the firmament of New York theater, the author of five critically acclaimed plays, two of which, “Appropriate” and “An Octoroon,” shared the 2014 Obie Award for best new American play.

Los Angeles has been a little slow on the uptake: Only Jacobs-Jenkins’ first play, “Neighbors,” has been produced here, in 2010 at the Matrix Theatre. In an essay last April, Times theater critic Charles McNulty took L.A. producers to task for their lack of vision, listing Jacobs-Jenkins as one of the “trailblazing new talents” whose “important new works … have yet to grace our stages.”

Read the latest Essential California newsletter >>

The Mark Taper Forum announced a production of “Appropriate” a few months later.

For dinner No. 1, with me, although he is not a vegan, Jacobs-Jenkins picked a vegan Vietnamese restaurant. He recommends the popcorn with nutritional yeast and lime zest, and shrimp somehow made of yams. The waitress approves of our order: “You guys chose, like, all the best stuff!”

I ask Jacobs-Jenkins what it is like to be on this ride — to open the New York Times Magazine last November, say, to find a profile of himself.

“I actually don’t read the press,” he says. “All the writers I admire were significantly reclusive, and I’m still trying to figure out how they got to a place where they didn’t have to talk to press.”

But he speaks through a chuckle and a wry smile, which soothe any sting. He doesn’t appear particularly uncomfortable; he’s relaxed and funny in conversation, and he wields the “like” and “do you know what I mean?” phraseology of his peer group with an elegance that, until this moment, I associated with only posh British accents.

“The stuff I write about doesn’t, like, necessarily leave people feeling warm and fuzzy,” he says. “I’m writing in a territory that’s, like, contested, and full of prickliness? And I find that people project their problems onto me, or something? It’d be one thing if I was writing rom-coms. I’d probably feel more comfortable talking to press. But I feel like my work kind of begins in a place of not knowing and anxiety and experimentation, and I expect that to happen in my audience. I wish I could make easier work.”

“You do?” I ask.

“Well, insofar as it would keep my blood pressure down.”

It’s a surprising thing to hear from a writer whose plays are so confrontational, even pugnacious, about cultural attitudes toward blackness. In “Neighbors,” for example, a mixed-race, upwardly mobile family gets a whole new set of problems when the Crows, who wear blackface and enact the cartoonish stereotypes of minstrel shows, move in next door.

“My dream was always to have an experience where an audience member would turn to another audience member, a stranger, and be like, ‘What did we just go through?’ And, like, kind of begin to talk.”

Even so, when “Neighbors” was first staged at the Public Theater in 2010, Jacobs-Jenkins wasn’t entirely prepared for what people would say.

“That play was built in a way to get audiences to a place …. ,” he says. “I mean, there’s a complete absence of closure, and it sort of ends on a sustained note of tension, and people just aren’t — people are just in a place. Every time I did a talkback, it would be horrible because people would want to pour their … whatever the play dredged up in them, instead of acknowledging that that’s part of the process.”

Although he found the experience traumatic, Jacobs-Jenkins didn’t retreat from controversy. “An Octoroon,” a wildly meta-theatrical adaptation of Dion Boucicault’s 1859 melodrama about interracial love on a plantation, “The Octoroon” begins with a version of himself addressing the audience: “Hi, everybody. I’m a ‘black playwright.’ I don’t know what that means, but I’m here to tell you a story.”

“Appropriate” is about a white family and doesn’t include a single character of color, but it’s nonetheless haunted by the legacy of slavery in the American South.

“Part of it was thinking through how invisible can I make something like blackness and still have it charge the room, because I was noticing in these plays that I was reading, like ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night,’ or ‘Death of a Salesman,’ or ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’ or ‘Buried Child,’ race is there, but we’re not reading it as there.

“And somehow when I write a play, it’s already there. I was trying to figure out what I’m doing that’s actually making you see that.” He pauses. “I’m not doing anything! You’re bringing your own weird feeling about what a story by a black artist is supposed to be.”

He recalls an argument he had with a creative writing teacher when he was an undergraduate at Princeton University.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines >>

“When I read books, I didn’t read, ‘Jane Eyre, comma, white, walked into the room.’ So I brought a story to class about two brothers dealing with their mother’s illness, thinking this is a universal story, and we talked about it craft-wise, and then there was this weird pause, and the teacher was like, ‘I guess my last question is, what race are these people?’

“It became this interesting fight in the room, between the students and the teacher,” he said. “That was the first time I realized that there was this expectation being placed on me as a writer who’s black. No one else had to explain that their characters were white, but I had to explain that my characters were black because there was an anxiety in the reader that I had to assuage.”

He was an anthropology major, and the subject can still send him into heady tangents about commodification, appropriation and ethnographers. He also took fiction writing classes, so many that, he recalls, the creative writing department told him, “‘You can’t take any more.’

“So then I decided just to take a playwriting class, thinking it would help me with my dialogue. I just felt the writing there was coming from a different place, and I could feel people listening in a different way,” he said. “My teacher, Rob Sandberg, took me to the top of a mountain, and was like, ‘You’re a playwright, and you should deal with that.’ And I remember feeling my life change as I turned around and went back to my room, thinking, ‘Now I have to figure out how to be a playwright. I have to now read all the plays ever written and understand what that means.’”

He proceeded to do so, more or less — he lists Caryl Churchill, Sam Shepard, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller and Eugene O’Neill as influences — while also getting a master’s degree from NYU in performance studies and a job at the New Yorker magazine, where he edited, wrote reviews and “got a kind of second education” from staff critics John Lahr, Hilton Als and Nancy Franklin.

He went on to win an emerging artists fellowship from the New Theater Workshop, a spot in the Emerging Writers Group at the Public Theatre and a Fulbright Fellowship to Germany, where he wrote the play “War,” commissioned by the Yale Repertory Theatre.

His most recent play, “Gloria,” about savagely competitive magazine interns, was written while he had a residency at the Vineyard Theater; he is in the Residency Five program at New York’s Signature Theater, which provides him a five-year residency and three full productions. He has also taught playwriting at both Princeton and NYU.

Getting him to drop these names isn’t easy; he confesses to the Fulbright, for instance, only after strenuous questioning about exactly what he was doing in Berlin. I grow a bit severe with him: Are there any other major honors he is playing close to the vest? A Rhodes scholarship, maybe?

He smiles: “I wish.” (Then a few days later I hear that he has won the prestigious Steinberg Playwright Award for emerging dramatists.)

As the waitress clears the plates, his thoughts turn to his ensuing dinner appointment. Does Hollywood tempt him?

“I love television,” he says, “and my love for it has made me curious about writing it. It feels like television’s moving toward something more novelistic, and that’s what I started wanting to do. But I can’t say that I’m dying to get notes from a studio. The artistic control that you get as a playwright is worth its weight in gold.”

He has built strong working partnerships with theater professionals. Mimi Lien, the set designer for “Appropriate,” designed “Neighbors” at the Public Theater and later worked on several iterations of “An Octoroon.”

On the phone a few days later, Lien talks about the urge she and Jacobs-Jenkins share “to make the audience feel something real,” a goal she associates more with performance art than traditional theater. “The things that Branden is writing about really deserve to be grappled with in a very real way, and we have had a lot of conversations about how to forge an event that will affect the audience viscerally.”

Eric Ting, who is directing “Appropriate,” meanwhile, is a close friend: “Branden was in my wedding party.” In a phone conversation, I share with him how pleased I was that a person with Jacobs-Jenkins’ inflammatory sensibility and in-your-face dramatic strategies proved so easygoing in person. Ting laughs.

“There’s a kind of built-in subversiveness to all of his plays, and I sometimes think there’s a subversiveness to Branden himself. He draws you in with his kindness and his laughter and his wit, just before he pulls the rug out from under you.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.