MOCA: Eli Broad discusses ousting of Paul Schimmel

- Share via

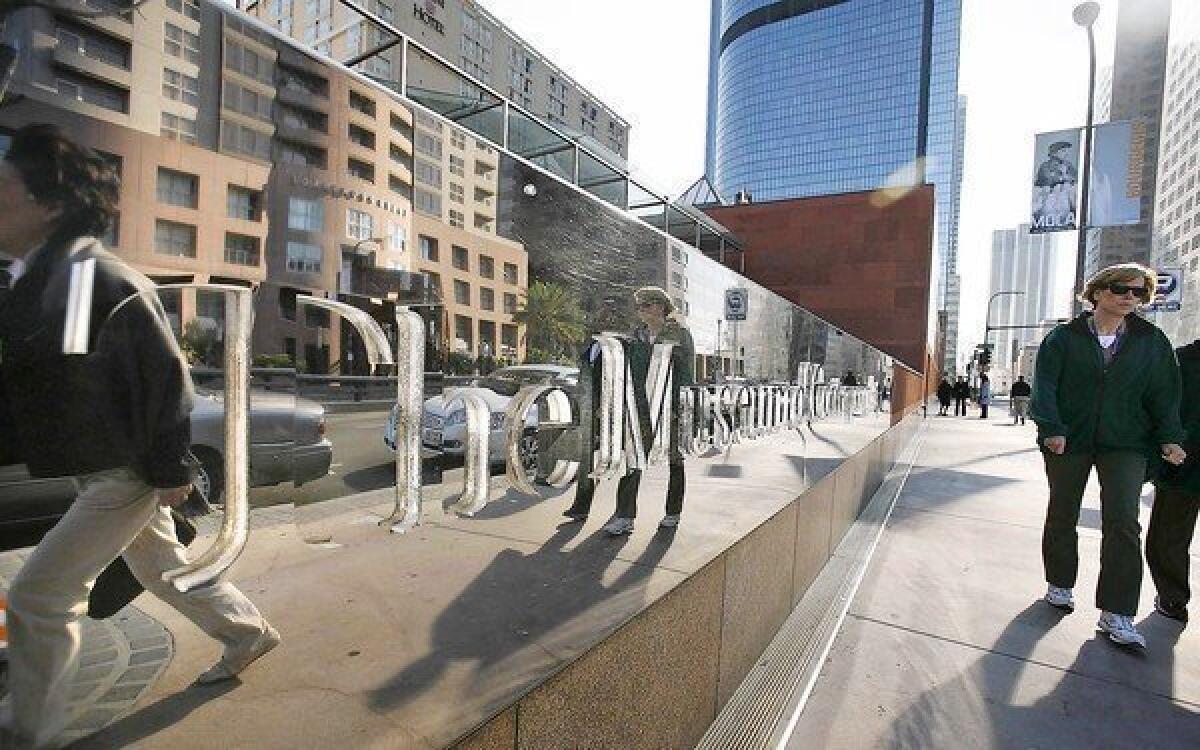

Inside the 12th floor conference room of his Broad Foundation in Westwood sat Eli Broad, the man the art world wanted to hear from after the forced resignation of Paul Schimmel, the longtime chief curator of L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

Broad, who helped found MOCA in 1979 and is now its biggest donor, didn’t have an official vote in the museum board’s decision to oust Schimmel — his status as a “life trustee” means he’s not a voting member. But he was present for a portion of the June 25 meeting where MOCA’s co-chairs, David Johnson and Maria Bell, negotiated an agreement calling for Schimmel to be paid his full salary for another year. (According to the most recent tax records, Schimmel was paid $235,000 in 2010.)

“It was no one event,” Broad said of the board’s action. “It was time for Paul and the museum to have a new beginning.”

That new beginning is now firmly in the hands of Jeffrey Deitch, the New York art dealer brought in two years ago as MOCA’s director.

Deitch’s buzz-driven vision of how to run a museum collided with that of Schimmel, who was known for sweeping, meticulously researched and often expensive exhibitions that examined themes and movements in contemporary visual art. Those shows and Schimmel’s acquisitions were vital to MOCA’s standing as one of the world’s most respected showcases for post-World War II art.

“They knew that Paul was from the old culture and was not getting along with the director,” Broad said of the board’s decision. “And although they had a lot of respect for his curatorial ability, they thought it was time to move on, especially some of the newer trustees.”

Normally, museum directors hire and fire employees without board involvement or authorization. But, Broad said, “the leadership felt that getting Jeffrey Deitch involved would create a bad scene which wouldn’t serve anybody.

“The bottom line is it was no surprise to Paul,” Broad said. “He’s a brilliant curator and he’ll be an asset in whatever he chooses to do going forward.”

How Deitch and MOCA fare going forward will depend not only on his signature presenting style, but on whether he has the fundraising clout to help pull MOCA out of the fiscal funk that has dogged it for more than 10 years.

Although the museum’s attendance rose from 149,000 the year before Deitch arrived to 402,000 in 2011, its last successful fundraising campaign was in the mid-1990s, and from 2000 to 2008 it burned through most of the proceeds. In 2008, Broad stepped with $30 million to save the financially depleted museum from going under.

Even with Broad’s help, MOCA is far from being out of the woods financially. The budget for the 2012-13 fiscal year that began this week is less than $15 million, according to a person knowledgeable about the museum’s plans but not authorized to speak publicly, the lowest since the 1990s. MOCA last week laid off five employees besides Schimmel. According to the museum’s most recent tax return, Deitch earned $648,281 in 2010.

In a departure from past practice, when MOCA would schedule shows before funding had been secured, it has adopted a policy of committing to exhibitions only after at least 80% of its projected budget has been lined up.

Deitch, who had no experience courting donors before taking over at MOCA, acknowledged in a public forum at an art fair last month that the difficulty of the task, a crucial and time-consuming one for museum directors, had come as “a rude awakening.”

“People wouldn’t take my phone calls because they figured, ‘he’s going to ask me for money,’” Deitch said, according to the online magazine Artnet. “People say it’s more important to give to hospitals or needy children than the museum.”

Now he’ll need to overcome bitterness in local art circles over the perceived indignity of Schimmel’s sudden exit.

Schimmel, 57, did not return calls, and Deitch, 59, declined to comment for this article, other than releasing a prepared statement: “I want to express my admiration for Paul and his great contributions to the art community. I am happy to participate in an interview about my plans for the museum in more detail at a later date.”

When Deitch took over at MOCA in June 2010, after closing his Deitch Projects galleries in New York, acclaimed Los Angeles artist Paul McCarthy and others thought that sparks between the new director and Schimmel might kindle a stronger MOCA.

“Both have done really great shows, both have a super awareness of the art world. I thought a dialogue between the two of them could make it into a really interesting place,” said McCarthy.

The hoped-for fruitful creative tension never developed.

Former MOCA staff members said that Deitch kept his own counsel while initiating populist projects such as “Art in the Streets,” a 2011 survey of graffiti and street art that drew a record 201,000 visitors, and smaller exhibitions focusing on art by the late actor Dennis Hopper and a James Dean tribute curated by actor James Franco. Besides the new emphasis on connecting art and celebrity, often interweaving music, fashion and other youth culture, Deitch brought a fast-paced approach in which shows could materialize in a matter of months rather than taking years.

In Schimmel, meanwhile, he was dealing with an institutional fixture who former MOCA senior curator Ann Goldstein, now director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, described in a recent email as “bold and resolute … an undeniable force [who] can push very hard to get what he wants.”

Deitch “gave us the impression he didn’t want to work with us,” discontinuing regular senior-staff meetings soon after his arrival, said one ex-staffer, who requested anonymity because of art-world sensitivities.

“I think reducing it to a Schimmel-Deitch binary is not seeing the complexity of the dynamics here,” said artist Lari Pittman. “You have a board that’s been problematic for a long time. Just to say it’s two people not getting along would be too easy.”

“It seems almost like a hostile takeover, but it seemed also like an aesthetic battle,” said McCarthy. “It seems like quite a change of philosophy at the museum, and that’s kind of scary from my point of view.”

McCarthy, 66, has worked with and respects Deitch, who curated an influential 1992 show, “Post Human,” that toured European venues and included him and a number of other artists who have worked with Schimmel and MOCA.

But Schimmel, he says, consistently has been a nurturing and insightful presence. McCarthy sees him as a friend, an important analyst and in some ways even a catalyst for his work. “It’s a discussion artists want to have — ‘what does Paul Schimmel think?’

“Jeffrey has always been supportive of my work, but I don’t understand the direction he’s taking the museum right now,” McCarthy said. “I see it as placating the populace. It’s not really what art’s about, but a ratings game.”

Among those in Deitch’s corner is Shepard Fairey, an art star of a younger generation, especially since he designed the “Hope” poster that became the unofficial image of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. (The design firm Fairey founded, Studio One, is now handling much of MOCA’s design work.)

In an email, Fairey, 42, praised Deitch’s “astute understanding of the interconnected nature of high and low art culture. When I say low, I don’t mean inferior.”

While noting that Deitch is well-grounded in the contemporary art tradition that MOCA has long emphasized, Fairey said he brings something extra.

“He also recognizes unique voices in areas the more conservative art world might not see as potentially sophisticated,” Fairey wrote.”I see Jeffrey as an early adopter, a translator and facilitator for new and sometimes challenging things.”

The traditional role of a museum director isn’t to curate but to oversee and fund the efforts of the curatorial staff, said Bolton Colburn, former director of the Laguna Art Museum. “It’s clear [Deitch] wasn’t using a curatorial department the way most leaders would.... He [was] acting in the role of curator, and usurping what their role was.”

With Schimmel’s departure, the curatorial staff has shrunk from five to three under Deitch, and the museum board says there are no plans to replace the chief curator.

Instead, MOCA will deploy more guest curators — a move that Colburn said means fewer in-house professionals coming up with ideas and nurturing contacts that can lead to donations of art and cash. “It’s a great way to save costs, but you’re not as tied in with long-term relationships.”

Some have speculated that Broad, who had played a key role in recruiting Deitch, had the museum director’s ear and was trying to tailor MOCA to complement the $130-million Broad Collection museum he’s building for his own contemporary art collection, across Grand Avenue from MOCA’s headquarters.

There has even been talk that Broad wanted to merge its collection with his own.

That supposition “is without any foundation whatsoever,” Broad said. “Categorically, no. If I wanted to do that, why would I have saved MOCA?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.