Appreciation: Joan Rivers, a singular comic with a writer’s conflicted heart

Meeting Joan Rivers, who had been cracking me up for as long as I can remember standup comedians making me laugh, was a dream come true.

When I was a kid I had a comedy album, the only one I’ve ever owned. I used it as material for my fellow fifth-graders. Jokes told by W.C. Fields, Burns & Allen, Groucho Marx and, of course, Rivers. I don’t think I used the Rivers’ bit in my act -- something about the reason a UFO never lands on a Jewish person’s lawn is they’d turn it over to see who made it -- but I remember seizing up with hilarity by the frenetic combustion of her delivery.

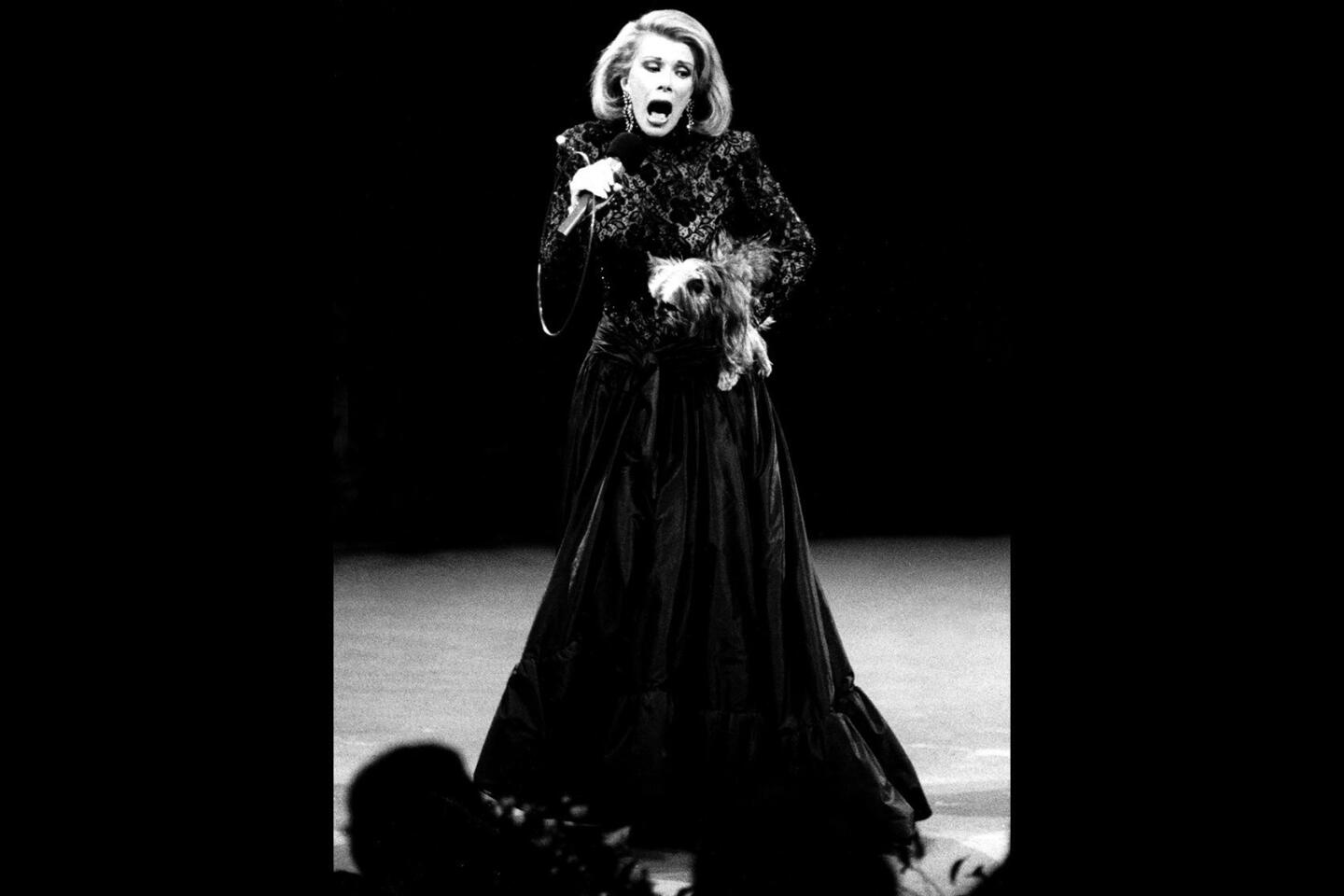

This was a comic who couldn’t be suppressed. Hers was a female voice, a New York voice, a Jewish voice and a voice belonging to someone who might have had more brains than beauty but that certainly wasn’t going to stop her from getting her fair share no matter what men might have thought.

I remember in high school staying up late to hear her “Tonight Show” monologues and laughing at her shtick about Heidi Abromowitz with my older sister, who I rarely got along with back then. In fact, this laughter was the one thing that bonded the two of us during those combative adolescent years -- humor enabling us to do what no parental injunction could manage: get along.

We’d stare at each other in disbelief at what would follow Rivers’ signature line, “Can we talk?” But those three words, not so much asked as insisted upon, were all that was needed to send us into a giddy space of subversive merriment.

In the conformist 1980s, there was an air of radical danger to Rivers’ act. She was part of the establishment only in the way that Lear’s Fool was part of his court--as a sanctioned truth-teller always in danger of going too far.

Her broadsides against Hollywood royalty and all those who caused her manifold insecurities to fester--dismissive family members, snotty stewardess (as they were called in the unenlightened pre-”flight attendant” days), men who acted as if she were invisible--were a secret solace to a young adult who didn’t fit the mold either and wondered if any good might come of it.

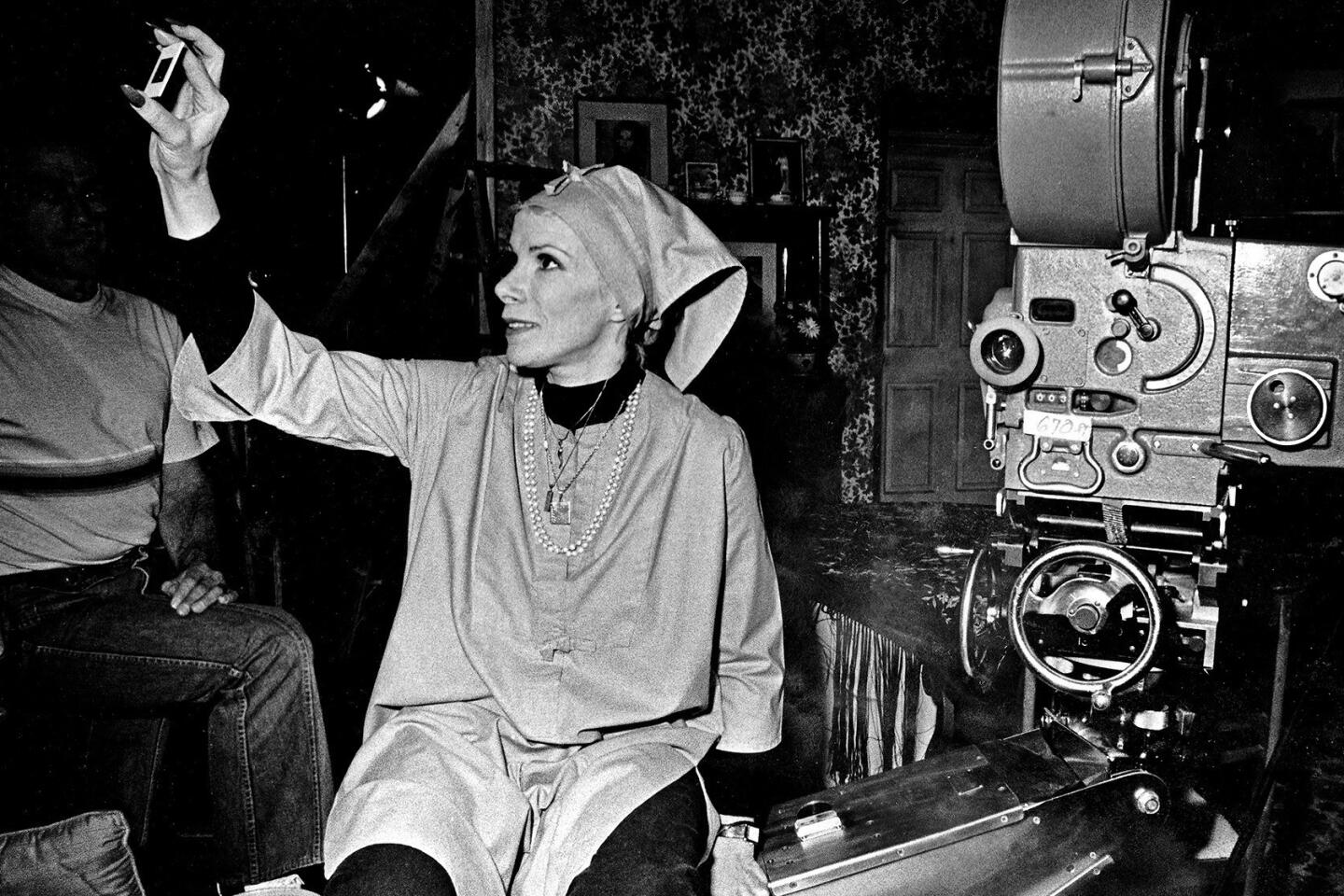

So about our meeting. We met at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre, where she was developing a show that would eventually come to the Geffen Playhouse. Her hair and makeup looked as if they had been attacked by a SWAT team of stylists.

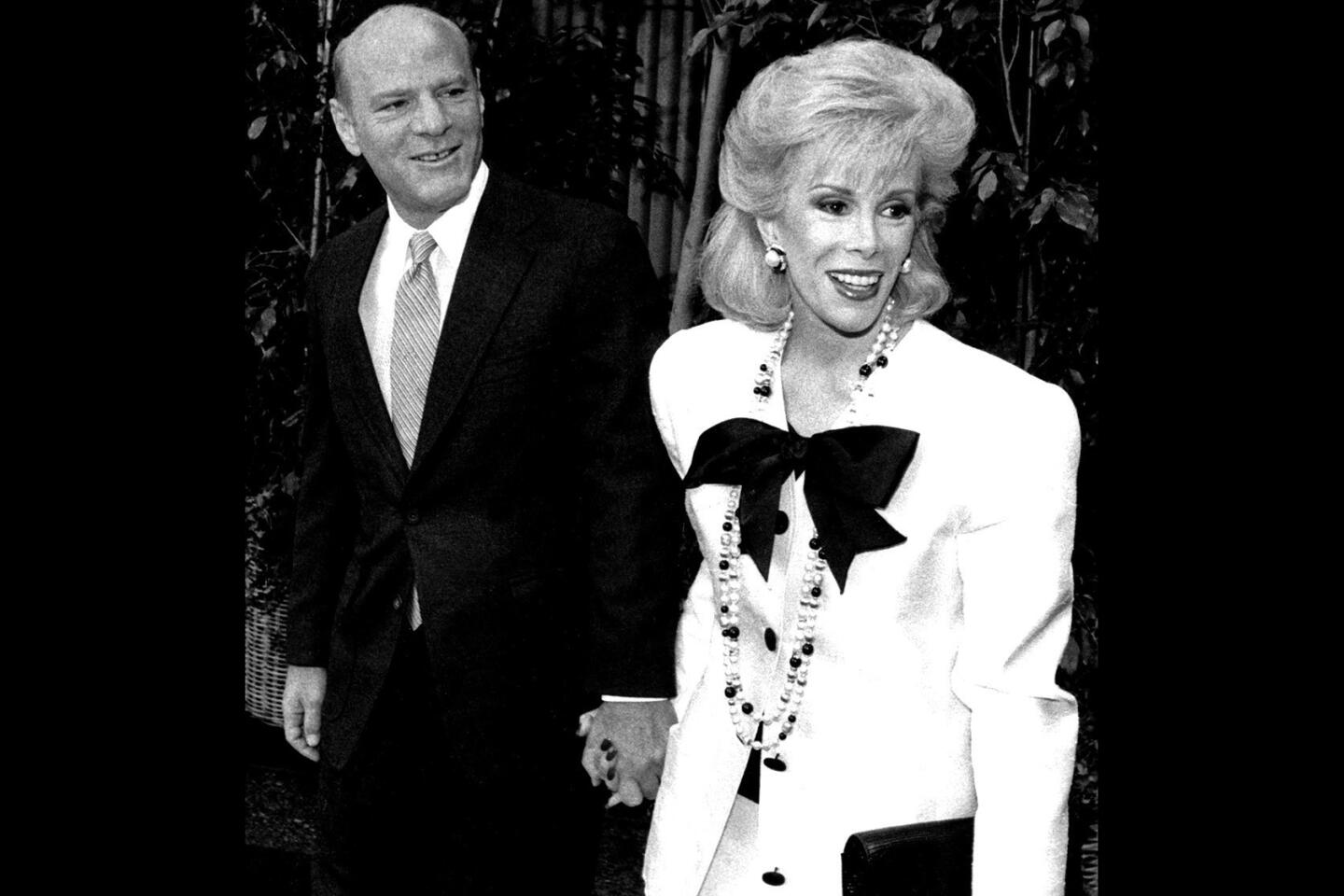

Merv Griffin had just died and she was set to talk to Larry King on CNN about the passing of a talk-show host who became for her the kindly yin to Johnny Carson’s vengeful yang. This was the excuse she gave for being all dolled up, but I don’t think she would have arrived for a professional meeting without ever looking her best. Which was pretty good, incidentally, for a woman in her mid 70s who had about as much work done as Michael Jackson.

Yet there was no phony façade with Rivers. She wasn’t hiding behind cosmetics or finery or even surgical alterations. What struck me about her was the clarity of her mind, the directness of her conversation and the generosity of her heart. She reminded me of a more glamorous version of my parents’ fellow Brooklyn-born upwardly mobile friends--those compulsive strivers who weren’t so much obsessed with conquering the world as making sure they didn’t end up back in Flatbush.

For a comedian who could say the nastiest things, she was capable of instantaneous empathy, especially when she sensed she was in the company of a fellow outcast who also wasn’t taking it sitting down. Gays loved her, and she loved them back--a solidarity of outsiders making it inside and improving the ambiance while they were there with their humor and style.

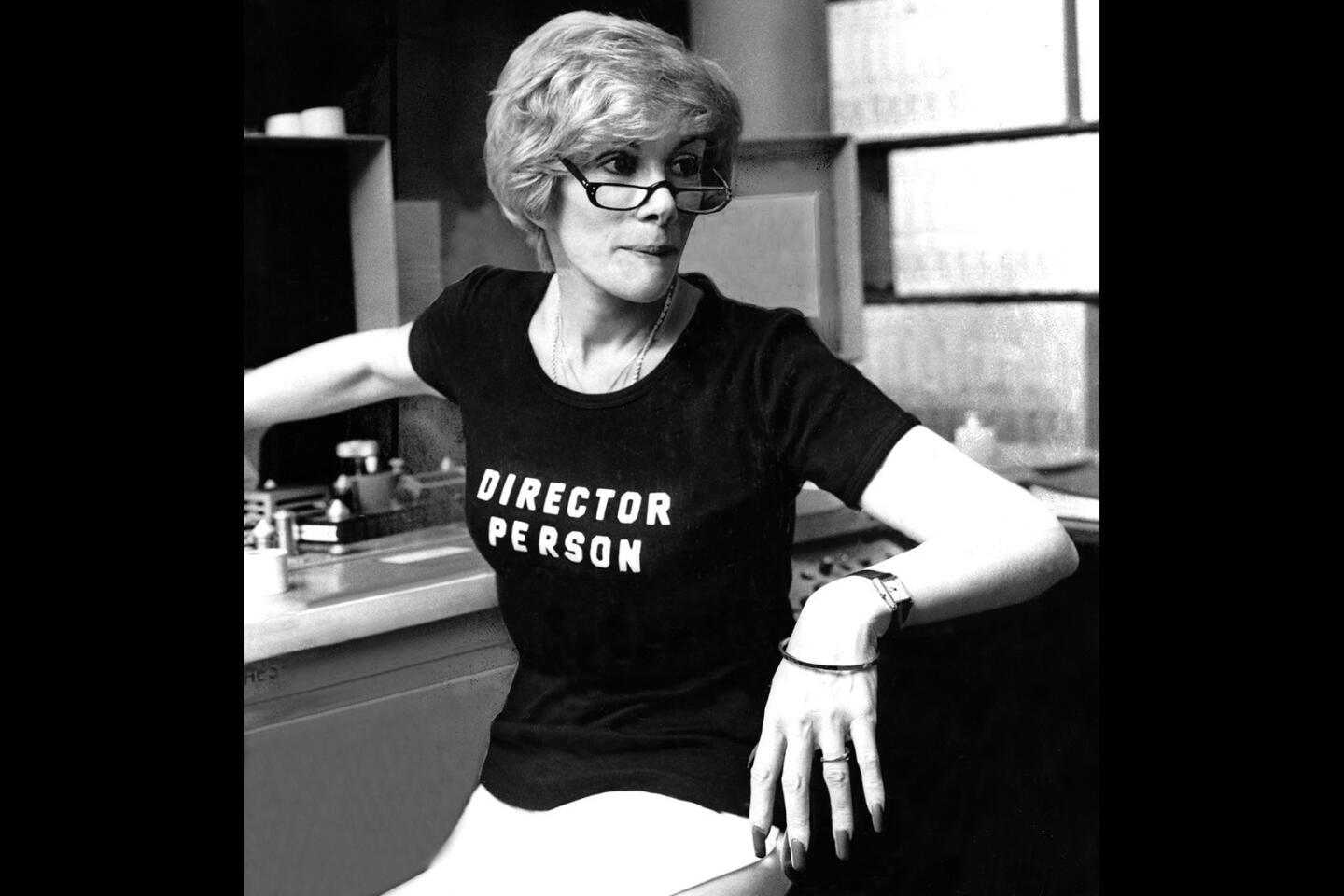

This Phi Beta Kappa graduate from Barnard also enjoyed being around cultivated people, intelligent minds. She knew the difference between fly-by-night success and those with a true vocation. Critics didn’t scare her. When it came to her work, she was capable of detached scrutiny.

I speak from experience. Because six months after I interviewed Rivers, I reviewed her show, “Joan Rivers: A Work in Progress by a Life in Progress,” at the Geffen. It wasn’t a pan, but with comments like “sporadically entertaining” and “belaboring her grudges,” it was hardly a rave.

That’s a critic’s life, I thought: alienating talents you admire with too much candor.

So it was a real surprise when Rivers’ assistant got in touch with me to set up a lunch date in Westwood. She wanted more feedback on the play she wrote with Douglas Bernstein and Denis Markell.

We met at Tanino in Westwood. She was relaxed, in good spirits and eager to hear more of what I thought. I told her that I didn’t think she should rush to New York with the play. Savvy about her own brand, she made clear that off-Broadway, not Broadway was her eventual goal, and that it would be better to develop the piece further in Britain, taking advantage of her fan base there. (The show went on to have some success in London and Edinburgh.)

More precariously, I suggested that she dig a little deeper into the Carson saga. I brought up an unflattering detail about her own behavior that she had confided to me in San Francisco but hadn’t made it into the play. I told her that if she wanted to create a better drama, she had to be willing to betray her own protective memory. She acknowledged the truth of what I was saying but nodded a wistful “I’ll take it under advisement” nod.

Sharing a meal with her didn’t feel like celebrity hobnobbing. It was more like having lunch with another struggling, conflicted writer. This wasn’t quite what I was expecting. When she complained to me in San Francisco about everyone forgetting that she had written Broadway plays (“Fun City,” “Sally Marr…and her Escorts”), I inwardly rolled my eyes. But not only could I feel her genuine respect for writers, including toiling critics, I came to respect her in the same regard.

I offered to pick up the tab, but she grabbed the check, saying, “What are you crazy?” We may both have been writers, but she had QVC.

In his poem “In Memory of W.B. Yeats,” W.H. Auden writes that “Time,” which can be “indifferent in a week/To a beautiful physique/Worships language and forgives/Everyone by whom it lives.” I think comics of Rivers’ caliber receive a similar pardon for their devotion to humor.

Rivers made enemies with her red carpet snark, unapologetic abrasiveness and tinderbox opinions. Her contradictions were writ large. As vulnerable as she was vituperative, as smart as she could be aggressively superficial, she was an underdog with an alpha dog’s bite.

Take her for all in all. We shall not look upon her like again.

Twitter: @CharlesMcNulty

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.