Commentary: After 2020, TV will try to return to ‘normal.’ We shouldn’t let it

We have come to what in other times would be recognizably the fall television season, but this year it is creeping in as subtly as a Southern California autumn. Like the rest of us, TV has been set back, rescheduled, de-scheduled. It is trying to cobble together a semblance of its normal self out of flotsam and jetsam: clearing out the pantry, borrowing from the neighbors, whipping up leftovers into something hopefully delicious. This means making a little new TV, with producers and personalities entangled at a distance; filling the gap with imported content (see “Transplant,” transplanted from Canada to NBC); bringing into network prime time series repurposed from cable or streaming (Season 1 of “Star Trek: Discovery,” coming from CBS All Access to CBS, all access).

In spite of this, and efforts to get the wheels of industry turning — fires are being stoked as we speak, deals made, series greenlighted — this would seem to be, fundamentally, The Year Without a Fall Season. And given the unreal reality show we’ll be stuck watching over the next couple of months, perhaps it’s just as well. How much attention do you have to spare?

So let’s look ahead, to fall 2021, with the supposition that things have returned to something like normal. Of course, these days it doesn’t profit a futurist, or any moderately sensitive soul, to look more than a week ahead; I wouldn’t dare to actually predict what television in 2021 will look like. We may be all too busy fighting in the streets to watch it anyway. No one knows where we’ll be with this virus. According to a recent Gallup poll, even with an effective vaccine, one in three Americans will refuse to take it.

To kick off our 2020 fall TV preview, the Times TV team selects the 15 shows we’ll be watching this fall — and that you should be watching too.

But just as the skies turned bright blue in the early days of the pandemic, when people took seriously the order to stay home — giving us an incidental glimpse of the better world we might consider trying to maintain — might there be a different sort of television in our future? This interregnum hasn’t offered us a blank slate, exactly, but nothing is going to be quite the same. What might TV look like? What might we want it to be? And what has this unfortunate time taught us that could be useful going forward?

It does seem likely, from various reports, that the industry will get back to making something that looks more or less like prepandemic television before the coronavirus is done with us. But should it model normal life before life returns to normal? As when a city jumps the gun in reopening, and people start acting like it’s suddenly 2019 again, it flies in the face of reality, which is already murky enough. To make new television without acknowledging disease and the need for distance will be to set stories in an unreachable past or to write science fiction. Last week, Seth Meyers, who, like other talk show hosts, has been shooting “Late Night” at home, indicated that a change was coming — his show is set to return to the studio next month — and the concerned citizen inside my head yelled back, “Stay put!” And not just because I think his show has been more interesting without a studio audience. I worry it sends the wrong signal.

And it’s true: Late-night television has been rewarding under quarantine — not as sparkly, sure, as when the band is in the house, but more focused, more intimate and more thoughtful, all qualities that these and coming times require. Bad jokes may fall flat without the mitigating effect of an audience groan or an ironic rim shot, but intelligent voices come through. (Jimmy Fallon has returned to a small studio space so he can hang out with the Roots, but guests are still Zooming in.) Now’s not the time for your cheers, as Bob Dylan nearly sang.

Similarly, the telecast of the Democratic National Convention, quilted from a hundred constituent parts, felt paradoxically more immediate, more true and more enlightening than an arena full of noise-making, sign-shaking, elbow-to-elbow delegates would have. Watching television deal with the structural limitations the pandemic has imposed upon it — its necessity-mothered inventions, its fresh aesthetic solutions to new practical questions — has been fascinating in itself, a more intriguing sort of novelty than “What crazy new game can we think of for Jimmy Fallon to play with his guests?” or “How can we change up Carpool Karaoke?”

Now that we have seen the stars in their quarantine hair, with minimal or no makeup, clad in their ordinary, albeit expensive civvies — the sort of “revealing” images that were once the exclusive province of paparazzi — the very notion of celebrity is being subtly recalibrated. The Emmys are about to show us what a red carpet looks like when it’s just whatever rug is on the floor of whatever room the nominees and presenters are set up to video conference. And we’ll see how much glamour such an arrangement can bear before it starts to seem just fake.

After playing off Kamala Harris at the DNC, the Oscar nominee and music legend is still pushing herself — this time in Starz’s wildly popular “Power” franchise.

Though no one wants a future made entirely of “Brady Bunch” grids, it does seem the case that television can look any way at all and still function capably as TV; that common ideas about how things have to look can be gone against; that stories can be told in many ways, according to available resources. We know that television can survive being stripped back to essentials. More than style and storytelling, we are in a moment that demands a new measure of honesty from a medium in which even reality shows and the news are dressed up, made up and glamorized.

The cultural pendulum swings between the rough and the slick, the simple and the sophisticated, the academy and the garret, the festival and the fringe festival. Punk rock, hip-hop, French New Wave film — all were born on the cheap, outside the system, in opposition to the system. For all that it is a moment thrust upon the industry, the pandemic is a punk moment, a period of forced authenticity in which money means relatively little; it’s the Ramones recording their debut album in a week as opposed to Fleetwood Mac taking a year to make “Rumours.” It’s a new look in which bad sound and blurry images are, if not ideal, absolutely acceptable: The bugs become the features. I am as sure as the next word in this sentence is “sure,” that from the stars and directors to the grips and gaffers, television will be only too happy to get back to treating itself swell, but it may be worth preserving this rough-edgedness as we journey back to a more polished “normal.”

There is something old-fashioned about this, something that recalls the early days of television, when production values were not necessarily worse but simpler, and the medium had not lost its regional flavor. There was a time when a TV show might come out of Chicago or Philadelphia before going national, like pop music scenes coming out of Athens, Ga., or the South Bronx. There are still some vestiges of this, usually news and morning shows, on commercial broadcast TV, and in public television, which is naturally responsive to the community from which it raises funds, even as it satisfies that community’s desire for “Antiques Roadshow,” Ken Burns blockbusters and British mysteries. But I dream of a world where, once again, a child in New York and a child in Los Angeles will grow up with memories of different kids’ show hosts, who might say their name on their birthday and be seen at local shopping centers making personal appearances.

Networked from remote locations, television during this time has had a dual quality of being both far-flung and extremely local, atomized and intimate. Whether talk show or drama or comedy — the first have been ongoing, the others more in the way of specials and experiments — they are all to some extent homemade: literally made at home, shot by the performers themselves, or by family members. You don’t get any more local than that.

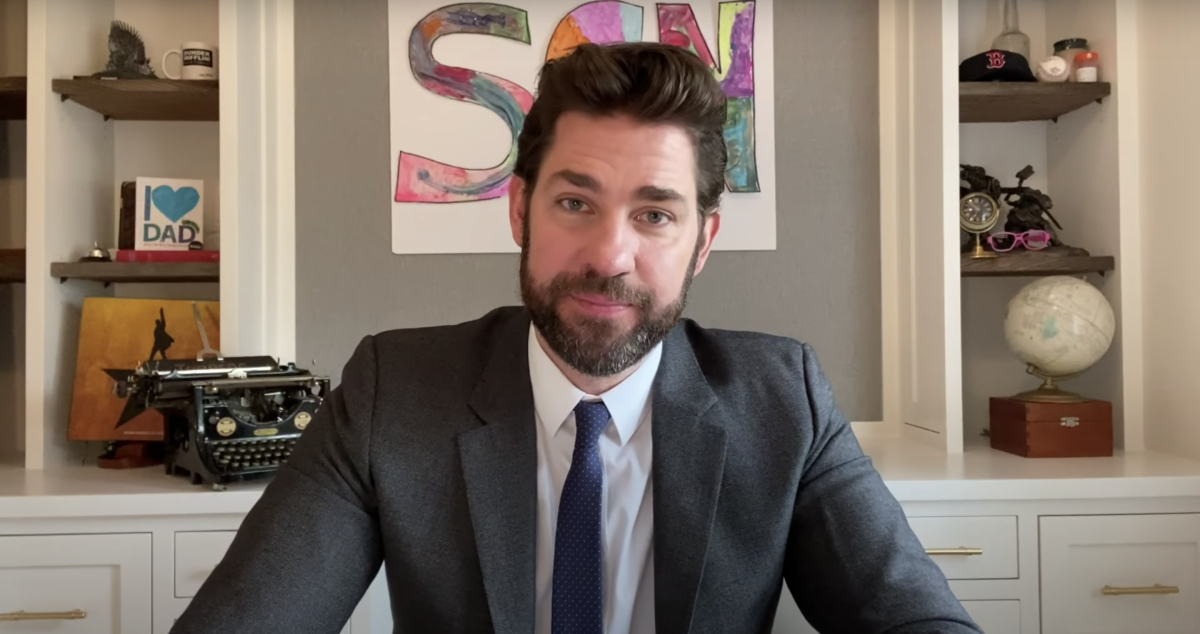

There is an element of compromise, of improvisation — not to say amateurism — to these efforts that I find appealing, like a nightclub made by the Little Rascals, or the Swiss Family Robinson Treehouse. John Krasinski’s “Some Good News,” which won the internet a couple of months back, had that quality. Yes, it pulled off a fancy “Hamilton” group sing, but its charm largely lay in a dude grappling with technology to make something happen online. We have all been that guy. Sold to CBS, the precise shape the brand will take is yet unknown, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they improve the fun right out of it.

Titanic corporate dinosaurs like ViacomCBS, Disney, Comcast and WarnerMedia will fight for dominance and survival until the last drop of blood freezes in their veins, and for the foreseeable and even the unforeseeable future we are bound to be bound to their dominance. But just as there were little nocturnal mammals scuttling around beneath the legs of the big lizards of the Mesozoic era, there is room for individual mutation, the oddball vision to survive, even thrive, within that ecosystem, and outside it: To return to that punk rock/hip-hop metaphor, the web is like an indie record store with shelves full of self-pressed singles and free ’zines by the door.

Hosted by Leslie Jones, ABC’s “Supermarket Sweep” reboot was filmed during the COVID-19 pandemic — but you might not know it. Here’s how they pulled it off.

And one doesn’t want to be a fascist about matters of taste. We’ve had quite enough authoritarian nonsense lately, and I happen to like a lot of things that, ratings and cancellations show, are not especially popular. My ideal television universe would consist largely of eccentric comedies and non-gritty mysteries. Any meeting of this paper’s TV writers is a reminder that we each use television in our own way.

But thinking bigger, if we can imagine a future in which humans act sensibly about climate change; and in which money is not the measure of all good; and where overnight delivery loses its grip on retail, allowing small, independent stores to flourish, bringing depressed downtowns back to life — if we’re dreaming, we might as well dream big; and we break up the media monopolies, at least a little, perhaps we can imagine as well a television that is fundamentally engaged with bettering the world. I don’t mean to say that it doesn’t do this, incidentally at times — smart shows do, I believe, make you smarter, and kind shows encourage kindness — and I don’t mean turning dialogue into sermons or drama into propaganda. Dan Levy turned “Schitt’s Creek” into a radical statement on love “simply” by creating a town in which homophobia never needed to be addressed.

Maybe I just mean for television to learn the lessons of 2020, to be a little more authentic, a little more local, a little less concerned with looking good. Makeup is nice, but you don’t have to wear it all the time.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.