Debate Mike vs. TV-ad Mike: How Bloomberg revived the relevance of the political TV commercial

The greatest advertising blitz in political history is allowing Mike Bloomberg to do an end run around independent media, much as Trump did in 2016. But will the billionaire’s campaign pass the Super Tuesday test?

If you were watching television during the run-up to this year’s State of the Union address, you may have seen a commercial starring Donald Trump:

“The real state of the union?” begins the narration.

“A nation divided by an angry, out-of-control president.

“A White House beset by lies, chaos and corruption.

“An administration that has failed the American people.”

It was catnip for the legion of Democratic voters who view Trump as the unholy spawn of Vladimir Putin and the Kardashians. Many had grown depressed watching their presidential hopefuls bicker over the ideological purity of health plans that Mitch McConnell would block in the Senate anyway. They yearned for the candidates to start finally taking the fight to Trump.

These days, running against a TV star demands having a huge TV presence yourself.

This 30-second spot did just that. Yet the striking thing was that this commercial didn’t come from Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren, “Mayor Pete” Buttigieg or any of the other stalwarts who’d spent long months in Iowa and New Hampshire traipsing through the slush and sampling Aunt Betty’s homemade fudge. No, this was an ad from Michael Bloomberg, the former New York mayor and ninth richest man on the planet, who shot to third in the national polls without spending a single minute glad-handing country folk.

The “Real State of the Union” ad and literally countless others — the Mike Bloomberg 2020 campaign runs 30,000 online spots a minute! — were part of the greatest advertising blitz in political history. And it came when everyone was saying that after the 2016 race, tweets, rallies and free media mattered far more than TV ads. As of Feb. 24, Bloomberg has already spent more than $500 million of his own money — over 90% of what Donald Trump spent to win the presidency in 2016 — and this was still a full week before Super Tuesday when Bloomberg’s name will, at long last, appear on a ballot. He’s already run so many different spots that, as a stunt, a writer for Slate watched 185 of them and ranked them.

This was a full-court press of a campaign, with ads boasting celebrity endorsements (Michael Douglas! Judge Judy!), ads talking about opioids and climate change, and ads obviously designed to troll the president, like those billboards proclaiming “DONALD TRUMP EATS BURNT STEAK,” or the golf-themed YouTube spot that ladles up carefully curated images of the president on the links looking clumsy and fat.

Yet for all the online spots, what makes the Bloomberg campaign unique is the carpet-bombing ubiquity of its television advertising. You’ve probably seen the one that assails Trump’s Pentagon visit when he insulted the brass (“Trump … attacks the war heroes in the room as losers and a bunch of dopes and babies”) or the one suggesting that the mayor and Barack Obama were allies — we see Obama praising Bloomberg’s “extraordinary leadership” — when in fact Bloomberg was no comrade of the president. Indeed, the campaign has aired so many TV ads featuring African-Americans that you might almost think Bloomberg was the founder of Black Lives Matter (unless, of course, you’ve heard of stop-and-frisk).

His commercials enter your home whether you are watching an NBA game, a soap opera, “Jeopardy!” or Fox News. They daringly defy the latest conventional wisdom that TV advertising has become passé in these days of online narrowcasting when algorithms tailor ads to individual voters’ aspirations, hobby horses and kinks.

The TV ads serve a defensive purpose. ... They let Bloomberg hide what is an obvious liability. ... He doesn’t do inspiring.

The data-driven Bloomberg is nothing if not hip to how information flows — he owns a media empire, remember — and wouldn’t throw his money away on a Hail Mary. He knows that ceaseless repetition is the most effective way of implanting a message in people’s heads. There’s a reason McDonald’s runs all those commercials even though it’s already McDonald’s. And Bloomberg knows that for people of voting age, TV is still the best way of getting yourself known. Television is how Donald Trump became a household name; indeed, it’s not for nothing that James Poniewozik recently wrote a book arguing that Trump embodied the very essence of that medium. These days, running against a TV star demands having a huge TV presence yourself.

Nothing better showed Bloomberg’s determination to do just this than during the Super Bowl, when he matched the president’s $10 million reelection commercial with a $10 million ad of his own. Carefully avoiding ideological issues like taxes and health care, his ad dealt with a cause dear to suburban moms, gun violence, and did so through the story of a grieving black Houston mother, Calandrian Kemp, whose son was shot to death and now backs Bloomberg because he’s working hard for gun control.

“Mike is not afraid of the gun lobby,” she says. “They’re scared of him. And they should be.” Whereas Trump’s commercial was all self-promoting triumphalism, Bloomberg low-keyed it, barely appearing in the ad and only in still photos. In pointed contrast to the president, Bloomberg suggests he cares less about being adored than about getting the job done.

The Super Bowl commercial wasn’t just skillful. It was also a brazen display of power: Everyone knows that such ads are staggeringly expensive. The profusion of his TV spots provides an almost hourly demonstration that Bloomberg is a man to be reckoned with. While the themes of his individual commercials aren’t irrelevant, of course, the deeper message is found in their sheer, shock-and-awe proliferation. Quantity changes quality. Each new ad reinforces Bloomberg’s claim that he’s the one candidate strong enough to scare — and defeat — Donald Trump.

After Bloomberg’s duff performance in the first debate, he quickly dropped 3% in the polls. Yet a few hundred million dollars in advertising can wash away many sins.

The TV ads serve a defensive purpose as well. They let Bloomberg hide what is an obvious liability: He exudes all the romance and charisma of an actuary. This helps explain why he ducked Iowa and New Hampshire, small states where you must shake thousands of hands and rev voters up — he doesn’t do inspiring.

Just as important, such ads allow him to do an end run around the independent media, much as Trump did in 2016. Why, he doesn’t even let his own reporters at Bloomberg News cover him! If he showed up on the Sunday morning shows, they’d ask him awkward questions about all those women’s NDAs, stop-and-frisk, redlining and his actual relationship with Obama.

Of course, you don’t make $61.9 billion without having a keen sense of opportunity. Bloomberg wouldn’t be buying all these ads if he didn’t think he had a good shot. Rather than spend the last year officially running, he bided his time, waiting to see whether a path might open up for someone with his particular (and unlikely) profile — a lapsed Republican moneybags known for racially inflammatory policies — to somehow become the Democratic candidate.

It was always clear that Sanders — whose potential nomination terrifies the party establishment — would attract a third of the party. The big question was, Who would be his moderate competition? For Bloomberg to enter, Joe Biden, a sentimental favorite with strong African-American support, would have to falter. This he has genially proceeded to do, falling short in his fundraising as he hopes for a strong finish in South Carolina and often sounding less like Obama’s sturdy, decent veep than everybody’s lovable Uncle Joe who has trouble typing in the Wi-Fi password — Democrats could picture him being steamrolled by Trump’s malarkey.

At the same time, none of the other candidates — Warren, Klobuchar, Buttigieg — managed to attract nonwhite voters, let alone turn themselves into a juggernaut. Fellow billionaire Tom Steyer seemed there mainly to prove that money isn’t everything (though his own ad barrage has given him a surge in the South Carolina polls, helping Bernie more than Uncle Joe).

This was the perfect situation for Bloomberg, who used his TV ads to position himself as the deus ex machina who would swoop down and save American democracy with his billions after the other, mortal candidates had thrown Democratic voters into a panicked despair that none of them could beat the Antichrist in November.

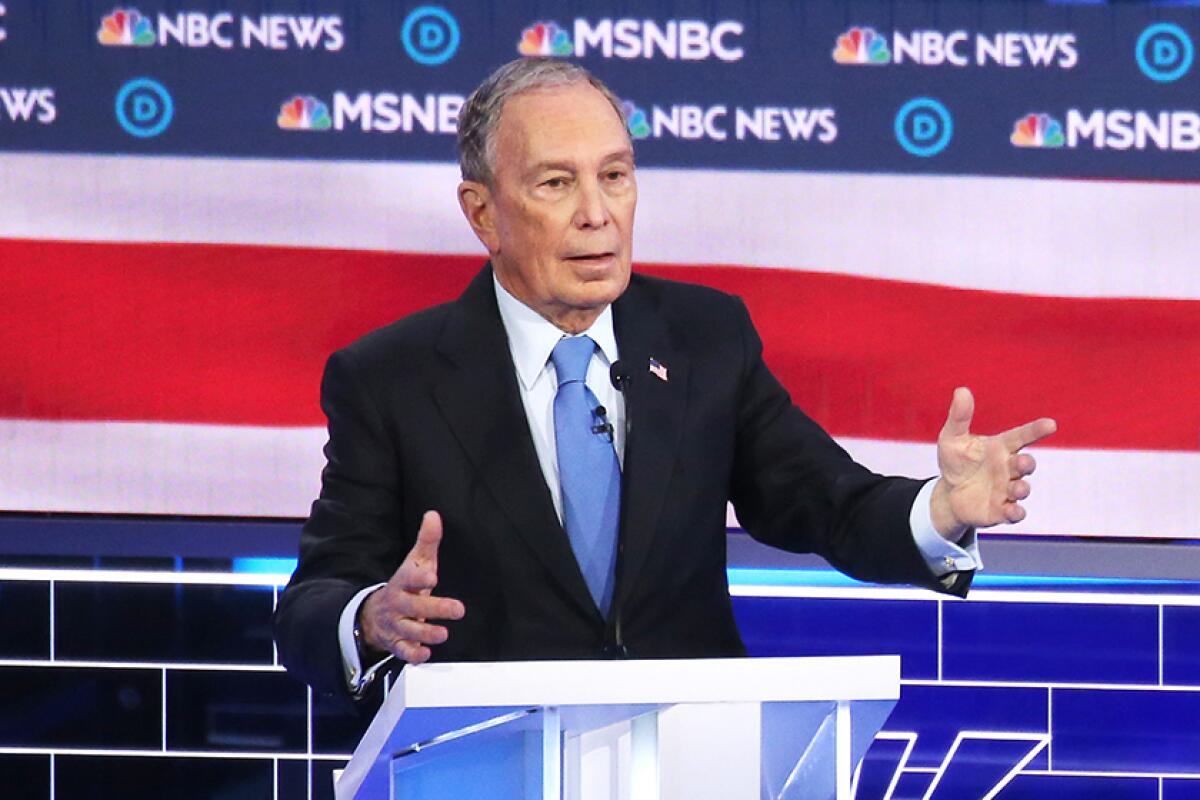

The flaw with this scenario became apparent when Bloomberg finally made his godlike descent onto the stage in Las Vegas on Feb. 19. Casual viewers might have been forgiven for thinking that he was simply part of a fundraising pitch for Elizabeth Warren, who gleefully demonstrated how to make a nose-to-tail dinner of a billionaire. After all those ads suggesting Bloomberg’s awesome power, watching the man in action — charmless, arrogant, unprepared for obvious questions — reminded one of the moment when Toto pulls aside the curtain to reveal the actual Wizard of Oz. You half expected a voice to say, “Pay no attention to the unhappy little man on your screen.”

Naturally, Bloomberg has faced his opponents’ accusations that he is trying to buy the election. But really, that’s almost the idea. Sure, he’s for fighting climate change and the gun lobby. And he insists he’d make a good manager. But in 2020, Bloomberg’s unsentimental selling point is that, in an election many Democrats fear may be the last honest election of their lifetimes, he has the Right Stuff: money. As his campaign manager, Kevin Sheekey, recently told Vanity Fair: “We’re going to spend Trump out of office.”

The power of Bloomberg’s billions was all over Tuesday night’s Charleston debate, where he rebounded a bit from his earlier debating disaster (about which he made a cringeworthy joke) and put on a peremptorily confident show as the Man Who Wants to Get Things Done. Clearly hedging his bets, he also paid for an end run around the debate itself by buying two network ads that aired during its breaks. (To address his problem with those NDAs, one was filled with female employees praising him.)

At one point, his psyche cracked momentarily open and he gave the whole game away. Speaking of the 40 new congressmen who turned the House blue in 2018, he said, “All of the new Democrats that came in, put Nancy Pelosi in charge and gave the Congress the ability to control this president, I bough... got them.” Somewhere Sigmund smiled. It was no surprise that the Twitterverse was filled with accusations that he’d actually bought off the debate audience too.

Hillary Clinton is more unvarnished than ever in “Hillary,” a new docuseries from director Nanette Burstein premiering March 6 on Hulu.

Then again, his supporters say, if you want to nominate a centrist, why choose the ex-McKinsey consultant mayor from South Bend, Ind. (pop. 102,245), who doesn’t even know how to shave properly? You want the macher in the bespoke suit who ran New York City for 12 years. True, lots of good white progressives look askance at businessmen who amass vast fortunes. But that only shows how out of touch they are with their base. Many poor voters, working voters and minority voters dream of owning their own businesses and achieving great wealth. They’re impressed by, not disdainful of Bloomberg’s self-made billions.

After Bloomberg’s duff performance in the first debate, he quickly dropped 3% in the polls. Yet a few hundred million dollars in advertising can wash away many sins, especially when one’s main rivals for the non-Sanders vote are facing money woes that should prove crippling heading forward. Bloomberg is in it for the long haul and reportedly is preparing to start siccing his ad dollars on Sanders, a juicy target after his strong finish in Nevada.

It remains to be seen whether Bloomberg’s grand strategy will work. If things go badly on Super Tuesday, his campaign may look like a rich man’s folly that no number of pricy ads can put right. Yet if he does even OK, he’s the one moderate with the resources to keep campaigning hard while Democratic party apparatchiks hatch their plans to stop Sanders.

Should it all fall into place for Bloomberg, you have to admit that Mike vs. The Donald would be mythic — two thin-skinned, media-savvy septuagenarian New York billionaires who’ve known each other for decades finally engaged in an assets-measuring contest. And talk about a difference in styles. Where Trump likes being president because it lets him think, “I’m the world’s biggest VIP,” Bloomberg has the quiet vanity of one who wants power more than attention. “I know what’s best for the world,” he’s always implying, “and I’m the best one to make it happen.”

There’s no knowing who’d win, but if this showdown happens, you can bet on two things: Those will be some TV ads worth seeing, and the loser could very well wind up behind bars.

Powers is the culture critic-at-large for NPR’s “Fresh Air With Terry Gross” and the author of “Sore Winners: (And the Rest of Us) in George Bush’s America.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.