RuPaul has ‘done everything.’ Except this

NEW YORK — The story, as he’s told it dozens of times over the years, goes like this: When RuPaul Charles’ mother, Ernestine, was pregnant with him, she went to see a psychic who said her unborn child, a boy, would one day be famous. Originally from Louisiana, Ernestine decided to call him RuPaul, a name inspired by the roux used to make gumbo — and, like “Madonna,” “Oprah” or “Prince,” one that seems to have ensured his celebrity.

But international stardom wasn’t exactly a foregone conclusion for a gay, black drag queen from San Diego. A fateful low point came in 1988. Though he’d attained a level of notoriety in the East Village club scene, broader success remained elusive. He wound up crashing on his little sister’s couch in L.A., watching “The Oprah Winfrey Show” every day and going on “The Gong Show,” where he was judged by Salt-N-Pepa and lost to an Elvis impersonator.

“I had done New York and couldn’t get any traction there. I thought, ‘Is this really it? Was the psychic wrong with my mother?’” RuPaul recalls. It’s a damp, snowy afternoon in Manhattan, flakes the size of quarters turning to slush the second they hit the sidewalk. Now 59, he sits in a dimly lit West Village restaurant near the apartment he’s shared with his husband, Georges LeBar, for a quarter-century. Clad in a wool cape and shawl-neck sweater in shades of black and charcoal, he strikes a more sober note than on “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” where he appears in suits of seemingly every hue.

Even when he hit the mainstream 27 years ago with the dance hit “Supermodel,” a send-up of the era when Cindy, Linda and Naomi ruled the runway, RuPaul seemed more likely to be a short-lived novelty act than an enduring cultural figure who would turn the subversive art of drag into a lucrative franchise, help revolutionize our understanding of gender and inspire a course at the New School.

Though half a dozen networks originally passed on it, his VH1 reality competition, “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” has won 13 Emmys in 11 seasons on air and spawned multiple spinoffs. It laid the groundwork for RuPaul’s DragCon — a drag convention held in L.A., New York City and London — to go with the multiple books, dozen albums, screen credits from “All My Children” to “Saturday Night Live” and popular podcast, “What’s the Tee.”

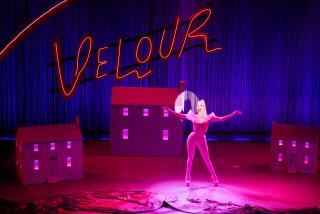

Now he’s coming to Netflix with his most ambitious creative swing to date. Beginning Jan. 10, he will star in “AJ and the Queen,” a road trip drama following a red-wigged New York City drag queen — one reminiscent of RuPaul himself — and a smart-mouthed 10-year-old girl as they travel cross-country via RV. The series, which he co-created with “Sex and the City” showrunner Michael Patrick King, features a big drag performance and cameos from “Drag Race” stars in virtually every episode. But RuPaul also spent significant time in the writers room and, in his first regular dramatic role, had to explore more nuanced emotions than on “Drag Race.”

“I’ve done everything in movies and TV, designed clothing and makeup lines. That’s where we are today in commerce,” he says. “Everybody in the world, we live longer and we must take a page from St. Jane Fonda’s book, which is, fit as many lifetimes in one life that you can.”

But David Bowie, not Fonda, provided his earliest creative inspiration. “That was the star I hitched my wagon to,” he says. Through the singer, he found a ”tribe” of like-minded “sweet sensitive souls” and, eventually, drag. When he met his idol, at a dinner party in New York in the late ’90s, RuPaul recalls being overcome with emotion and hiding in the library, where Bowie found him and introduced himself. RuPaul left the party soon after, walking all the way downtown from the Upper East Side, “screaming and crying the whole way because I met David Bowie.”

After a stint in Atlanta, where he was a regular on public access TV, he eventually landed in New York and became a fixture in an edgy downtown drag scene centered at the Pyramid Club in the East Village. The defining ethos was, as he puts it, “F.U. Reagan.”

But he grew frustrated with his niche. “I knew that people loved me in drag. But I thought, ‘I can’t become famous in drag. That’s cute for below 14th Street. But how am I going to make it to Cahnuhgie Hawwl?’” he says, putting on a thick Noo Yawk accent.

During his couch-surfing, “Oprah”-watching stint in SoCal in 1988, he received a phone call from his friend music producer Larry Tee, urging him to come back to New York. RuPaul describes this as the point he decided to adopt a new philosophy: “Give. These. Bitches. What. They. Want.” And what “they” wanted, apparently, was over-the-top glamour, not the punk-inflected drag he’d been doing. He shaved his legs and chest, and within a year won the Queen of Manhattan drag pageant.

“It felt like ancient doors went creaking open,” he says, prying an imaginary door with his clawed fingers, “and I walked through and I became world famous. ... The biggest obstacle I’ve ever faced is my own limited perception of myself.”

If “we’re born naked and the rest is drag,” as he’s been saying for nearly 30 years, RuPaul is practiced at the art of celebrity profile drag — of speaking with a blend of bawdy wit and self-help earnestness that makes him a quotable, captivating storyteller without requiring him to reveal much about himself. But while it may be well-honed, the anecdote sheds light on why RuPaul hasn’t retired the blond wig after three decades, even as he insists he’d be happy to give up drag.

“He loves it so much. He lives and breathes it. But now he knows that people want him in every element of his life,” says “Drag Race” judge and longtime friend Michelle Visage, who first met RuPaul in the late ’80s New York club scene, when he’d adopted a drag persona known as “Bianca Cupcake Dinkins” — the illegitimate daughter of New York Mayor David Dinkins. (“It was more streetwalker than Glamazon,” she clarifies.)

RuPaul, who briefly starred in an episode of “The Comeback,” King’s excruciating cringe comedy about a washed-up sitcom star, had been impressed by the writer’s ability to give laser-like adjustments to his performance. Years later, his agent set up a meeting. He walked into King’s office and noticed a still from the Preston Sturges film “Sullivan’s Travels” — one of his favorites — hanging on the wall.

“AJ and the Queen,” in which RuPaul’s character, Robert (a.k.a. Ruby Red) and a scruffy stowaway, AJ. (Izzy G.), make their way through red-state America, is a mash-up of “Sullivan’s Travels” and “Paper Moon.” A recurring theme of the series, articulated by Robert, is that “no one is just one thing.”

RuPaul describes the project as a “love letter to the America we were promised as kids. And yes, we’ve had a …” — he pauses — “major hiccup with that. But Oprah told me this — name drop, whatever — but she said, ‘We all thought that progress was linear, but that was our mistake. Progress is not linear. It goes sideways.’ ”

King, who compares his collaborator’s sometimes enigmatic presence to that of a “mystical Egyptian cat,” nevertheless suggests that RuPaul has a rare ability to transcend the barriers explored in “AJ and the Queen.” “He’s taken this very outsider thing and included everyone,” he says, voice breaking. King recalls an MTV News segment of RuPaul charming shoppers at a New Jersey mall in 1993. “What he’s done is what he did at that mall. He’s just done it in America’s living rooms in 2019. He just stayed the course and either his light got bigger or the world caught up.”

Working alongside Izzy G. for months forced RuPaul “to re-parent my own 10-year-old child.” As such, “AJ and the Queen” is likely to appeal to the group he says is his core audience: not urban gay men, but “smart, 13-year-old suburban girls.” This demographic is wary of joining “the assembly line of synthetic femininity” and understands, on a gut level, that drag mocks this performance — the big lips, the fake boobs. “I see how ridiculous it is. I’m going to align myself with other people who also see how ridiculous it is. Drag offers us the ability to mock identity and flip our middle fingers up at the sexual hierarchy that has shunned us. Hoo! Can I get an amen?”

“I think little girls my age look up to him,” says Izzy G., 11, who communicates with RuPaul over text and Facetime. “For me, when he’s in drag he represents a strong, independent, amazing woman.”

RuPaul has also set an example and created opportunities for a new generation of drag performers, many of whom have followed him to crossover success, such as three-time “Drag Race” contestant Shangela — a.k.a. D.J. Pierce — who appeared in “A Star Is Born.” “As African American, gay drag queens, we live with more adversity and challenges,” says Pierce. “Seeing RuPaul go out there and not only create music, but TV and film roles, and continue to go down so many creative avenues — that is inspirational. For a person of color like myself, I see RuPaul and I say, ‘Oh, honey, I can do it too.’ ”

“Drag Race” serves as an introduction to drag for many young queens. RuPaul says he can see the downside of the show’s influence — the rote, bitchy mimicry it inspires — when he’s reviewing audition tapes.

“One in 10 does something different that makes me go, ‘Oh, who is that? Those other nine people — no exaggeration — do the exact same thing. They say, ‘RuPaul, you need me on your show because I will cut a bitch.’ That specific line. It’s so funny. Anytime someone does something remotely unique or to their own rhythm, I mark them down.”

But with mainstream visibility has come scrutiny. Though RuPaul is credited as an LGBT pioneer, and says he’s always found “sanctuary” in the irreverent, that spirit doesn’t always sit well in an era when ideas about gender — and the language we use to describe it — are shifting rapidly. RuPaul has faced criticism for comments about trans contestants.

He’s also had to field constant questions about the co-opting of drag, something he is not concerned about because, he says, “At its base, drag is about making fun of identity. Drag could never be mainstream in an egocentric culture.”

Some of the reactions to the show are “interesting,” he says, in a way that’s clearly not meant as a compliment. “People take themselves so … seriously. And God bless them. If that’s going to work for you, right on, but I know where that goes. That’s a dead end,” he says. “There are things I take seriously. I take kindness seriously. I take love seriously. Everything else — pfffft,” he makes a raspberry sound.

In a rare setback, Rupaul hosted a daytime talk show in a three-week trial run last summer, but studio Warner Bros. will not be moving forward with the project. But the “Drag Race” franchise continues to grow — with international versions in Thailand, the U.K. and, soon, Canada.

“I’m going to keep doing it ’til the wheels fall off this …” he says of the show, using an Oedipal expletive. “What I love about what drag has offered me is the ability to be creative in this way. That’s my passion. That’s what I live for.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.