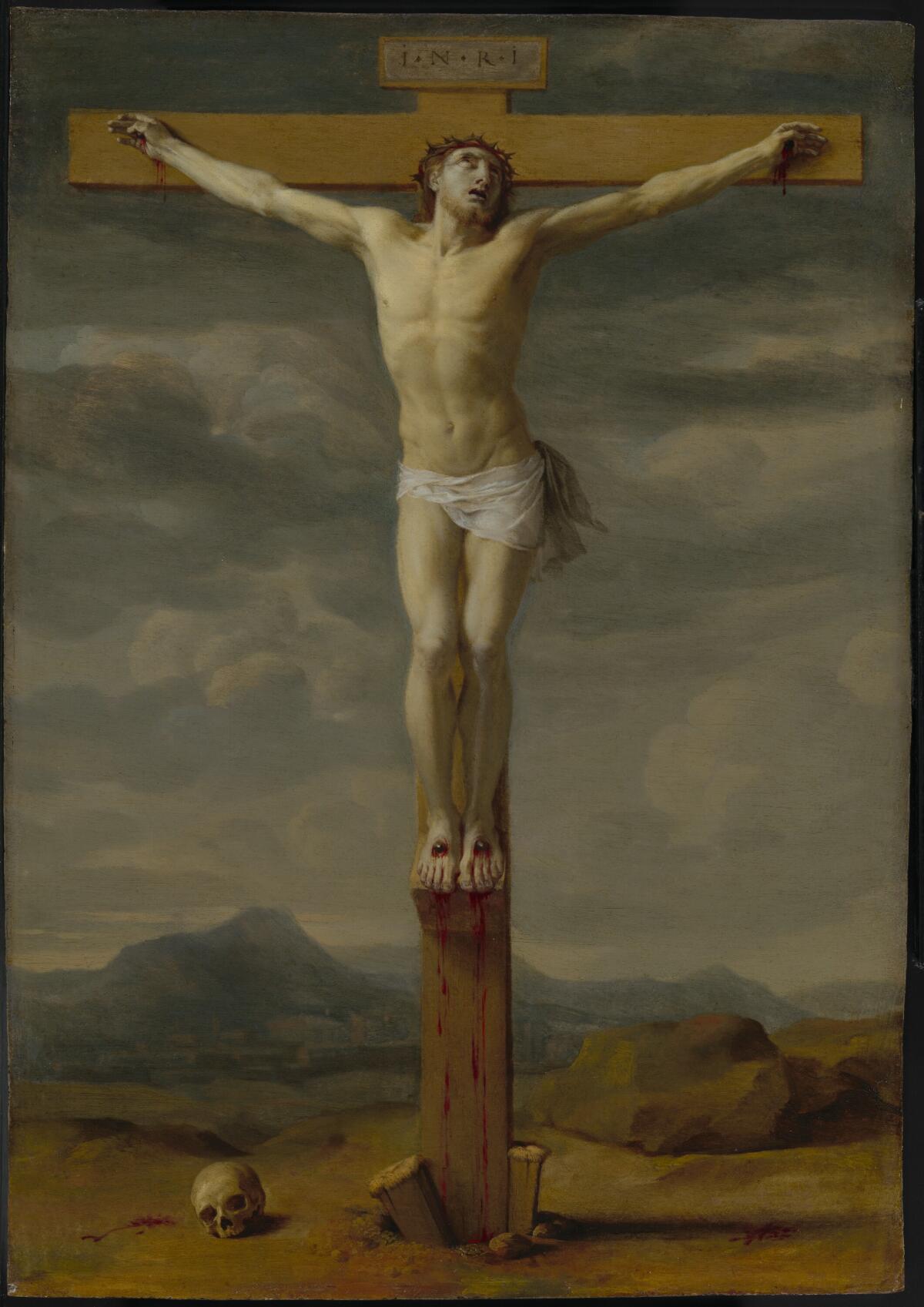

1650-55, oil on copper; East Pavilion, Gallery 206

Not a lot is happening in this smallish picture, which was made for personal, one-on-one contemplation. Except for the cross, the landscape image is largely blank.

The action, if that’s the right word, is focused on the slow, agonizing process of bleeding to death, narrated by blood trickling from the hands and feet of a crucified Jesus. Le Sueur (a founder of France’s Royal Academy) has removed almost every potentially distracting object, leaving behind a totally barren landscape, the merest vague suggestion of a distant village and a sky empty of everything but threatening clouds. He’s drained all the color too.

Except, that is, for red. Amid a range limited to neutrals — grays, tans, browns, off-white — bright crimson blood stands out. The blood marks the brutally nailed palms and feet, runs down the wood and trails across the ground, leading to a skull lying at the foot of the cross. The remains of Adam, the first man, were said by early Christians to have been buried at Golgotha, site of the crucifixion.

Here, the juxtaposition says “the new Adam” hangs dying on the cross. Le Sueur omitted the women who stayed throughout the crucifixion’s horror, in favor of featuring Adam’s skull, symbol of Catholic patriarchy. The painting is a fastidious, tightly controlled image hinged on the pain of starting over.

EAST PAVILION