Conducting has long been a male-dominated field. A new documentary aims to change that

- Share via

Filmmaker Maggie Contreras was in her car, listening to NPR‘s “All Things Considered,” when she heard a report that piqued her interest.

“The world of orchestra conducting is still dominated by men. Less than 10% of major U.S. orchestras are directed by women. In Europe, it’s less than 6%. A recent competition in Paris is trying to change that by promoting the talent of budding female orchestra conductors...”

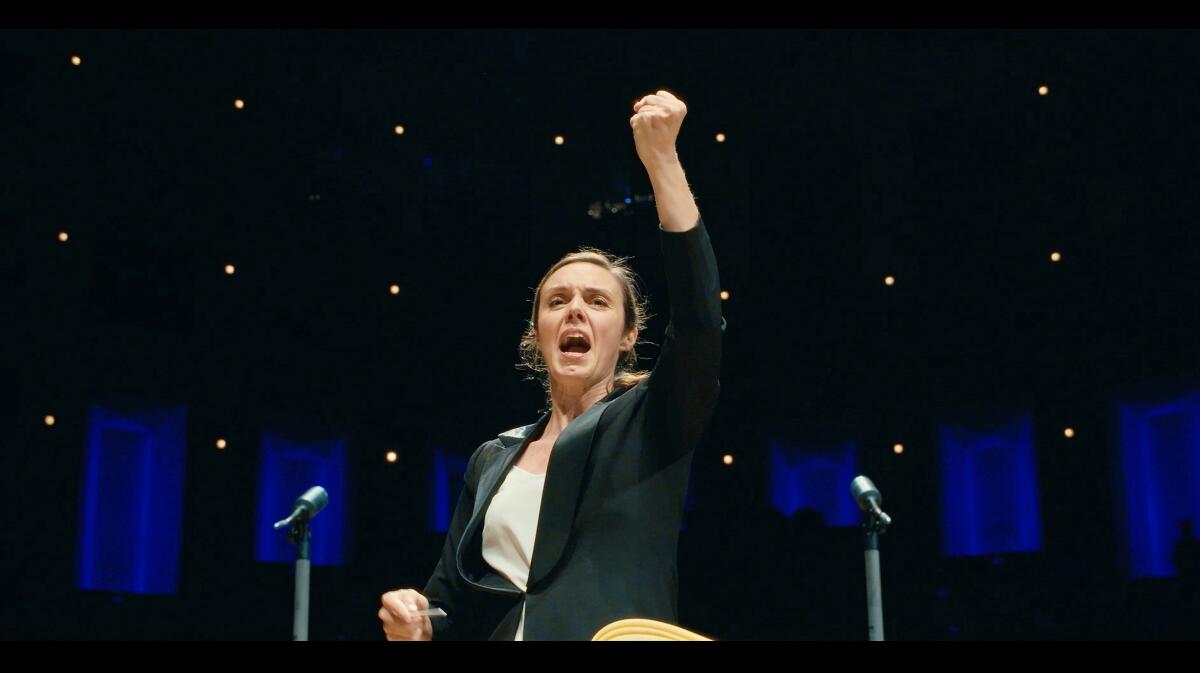

Over the next two years, Contreras immersed herself in the world of classical music, filming an elite cadre of female conductors with dreams of winning said contest, La Maestra, the first international conducting competition solely for women. Contreras’ resulting documentary, “Maestra,” recently had its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival.

“I grew up on the wrong side of the tracks in Tucson, Ariz., but I have been around classical music my whole life,” says Contreras, 39, whose background is in classical theater and acting. “Even though the gilded concert halls of Paris were far away from me, music was always a part of my life because of the people around me who appreciated it.”

After several years of working as a producer alongside filmmaker Neil Berkeley (“Gilbert”), Contreras was ready to get behind the camera. She set her sights on the second La Maestra competition, scheduled for March 2022.

But it took the first-time director almost a year just to secure access to competition. Finally, with contract in hand, she reached out to contestants — by now whittled down to 14 from a pool of 202 applicants — to persuade them to open their homes and their lives to the cameras.

Initially, Contreras followed seven women. For the film, only five made the cut.

“We had a very short time to dig into these women’s stories. We had to get people to fall in love with these women so that they cared about what was at stake,” she says. “We also had to teach people what the heck is conducting because if they don’t know what they’re looking at, they’re not going to be able to fully appreciate the competition.”

Contreras journeyed to Iowa City, Iowa; Atlanta; Albuquerque; Krakow, Poland; and Athens before finally arriving at the Philharmonie de Paris. The entire time, she says, she raised money on the fly.

“I literally sold my car to make this film,” she says. “It was always, ‘Do we have enough funding to do this stage? Now this stage? Now this stage? At every single stage, it could have ended right then and there.”

But she got an early boost when David Letterman, a classical music fan, signed on as an executive producer. And the timing of her film, for which she is seeking distribution, was fortuitous. “Maestra” arrives on the heels of the controversial, Oscar-nominated “Tár,” the 2021 Tribeca premiere of the documentary “The Conductor,” and ahead of Bradley Cooper’s Netflix biopic about Leonard Bernstein.

“It was a coincidence,” she says, laughing. “It was like a conductor zeitgeist.”

Who in the classical music racket wouldn’t want an Oscar contender drumming up more attention for the art form? Maybe more of us than you might think: The mean-spirited ‘Tár’ gets just about everything about classical music wrong.

The La Maestra International Competition for Women Conductors was launched in 2019 by the Paris Philharmonic and Paris Mozart Orchestra to showcase and provide opportunities for female conductors worldwide. The first edition took place in September 2020.

International competitions like La Maestra can help launch careers and provide exposure. L.A. Philharmonic’s Gustavo Dudamel was “discovered” at the Mahler competition in 2004, and five years later the then-27-year-old Venezuelan joined the L.A. Philharmonic as its music director. He will lead the New York Philharmonic beginning in 2026.

“The idea of giving a platform and shining a spotlight on talent and just exposure and networking and connections so that these women can be seen, I think, is critical,” says Marin Alsop, a 2022 and 2020 La Maestra juror.

She would know: Alsop was the first woman named to lead a major U.S. orchestra when she was appointed music director of the Baltimore Symphony in 2007 and was the first woman to serve as principal conductor of Britain’s Bournemouth Symphony. She was recently named artistic director and chief conductor for the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra. Despite her extensive credentials, she says has felt the sting of resistance along the way, including from members of the Baltimore orchestra immediately after she was appointed there.

The classical music world has a long history of dismissing the notion of women on the podium, who were often seen as “freakish outliers,” says Deborah Borda, president and CEO of the New York Philharmonic and formerly of the L.A. Philharmonic.

“Even in the ’90s when I managed the New York Phil the first time, people were very resistant to female conductors,” she says. “A lot of the older men didn’t think it was natural for a woman to conduct an orchestra.”

Borda, who chaired the 2022 La Maestra competition, oversees an orchestra that is now 53% women. In 2020, the New York Philharmonic launched Project 19, a multiseason initiative to commission and premiere 19 new works by 19 female composers. And, she adds, the orchestra’s youth concerts often feature female conductors.

“If you’re a little boy or little girl, and the first concert that you see is conducted by a woman, you’ll never think about it again. It will be completely natural,” she says. “Things like that will change the course of history.”

When it comes to making music, gender should be irrelevant.

For Zoe Zeniodi, La Maestra had a unique appeal.

“I started conducting late, so I only could apply for things that had no age limit. This competition was the only one,” the conductor said via Zoom from Athens. “I really had no hopes of being selected.”

Zeniodi, 47, already had a successful career as concert pianist in Greece but came to the U.S. to study at the University of Miami, where she was introduced to conducting by a professor. “I took his class, and he saw me conduct and said, ‘You really have to go into this profession,’” she says. “To be honest with you, my first response was, ‘I can’t — I’m a woman.’”

As a freelance conductor, she spends much time on the road — often without her young twins. This month, her schedule has taken her to Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, then later this summer she’ll head to Australia, where she will conduct at Opera Queensland. Next year, Zeniodi will assist James Conlon at Los Angeles Opera, where Lina González-Granados, the third-place winner from 2020 La Maestra, now serves as a resident conductor.

In the film, Zeniodi is seen FaceTiming on her phone with her son, trying to persuade him to eat his lentils. That scene, Contreras says, was filmed backstage at the concert hall just before the conductor was set to hit the stage.

“I actually have two lives happening at the same time,” Zeniodi says. “It’s true, life before kids was very different; it was much easier. But my personal view is children are the most important thing in the world.”

Former Dudamel Fellows are showing up everywhere, from the Hollywood Bowl to the Proms. It’s a diverse and L.A. Phil-centric generation of conductors.

During a grueling four days, the quarterfinalists are judged as they rehearse with the Paris Mozart Orchestra and again as they conduct in front of an audience at the Paris Philharmonic concert hall. The film, made with a crew that was 80% women, intersperses concert footage with moments of quiet reflection, then back to the suspense-filled scenes as the 14 contestants are pared down to six and finally three. Contreras worked with the arts channel Arté, which livestreamed the competition, to shoot concert footage for her film.

But the drama doesn’t take place only on the stage. The women share their hopes, fears and personal stories of psychological trauma, discrimination and sexual abuse. One contestant visits her childhood home, reliving the pain of rejection by her parents. Another questions the value of her participation in the competition, which is taking place a week after the Russians invaded her home country of Ukraine.

“I did not set out to make a social issue film — that’s not the type of filmmaker I am,” Contreras says. “I want a good story; I want to be entertained.”

La Maestra’s top three conductors receive cash prizes of up to 10,000 euros. But more important, says contestant Tamara Dworetz, is the chance for some to participate in the La Maestra Academy, a two-year program that facilitates conducting opportunities and provides mentorship and assistance.

Dworetz, 34, who studied with conductor Bramwell Tovey, was the only American who made it to the qualifying rounds in the competition. Through the academy, she has served as assistant conductor to Klaus Mäkelä of the Orchestre de Paris and to François-Xavier Roth of the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne.

“Being a conductor can be a very isolating position — especially early on,” she says. “To have someone who’s your champion, your advocate, and then receiving opportunities like the assistant conductor of those two orchestras is huge.”

Today Dworetz works as the director of orchestral studies at Georgia State University and recently was offered a position to lead the Georgia Philharmonic in Roswell, Ga. The onetime public school teacher is a fervent believer in education as the key to change.

“I hope people start to open up their vision of what a conductor might look like, what they might behave like, how old they are,” she says. “It’s got to start from childhood. Everyone should have the chance to have a relationship with classical music.”

‘The Conductor’ review: Director Bernadette Wegenstein’s documentary profiles classical music’s Marin Alsop.

Alsop has been an early leader not only on the podium but in creating programs to secure a path for future generations. Among her many efforts is the Taki Alsop Conducting Fellowship, created in 2002 to mentor and support women conductors.

“It’s so important to build community so you have a support system,” she says. “That’s what I’m trying to build. And I think that La Maestra adds to that. They’re trying to enlarge the circle and create more opportunities.”

Alsop stepped down from Baltimore in 2021, and now only a handful of women lead top orchestras. The pandemic, the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements forced arts organizations to pause and assess their institutions and programming. Already there are signs of change.

“I believe this will be sustainable. I think we’ve passed a tipping point, which is good not just for women but for underrepresented people,” Alsop says. “We’re nearing a moment when people can feel more courageous taking chances.”

Contreras’ film lifts the curtain on “women inhabiting spaces that have been almost exclusively male,” she says, noting that she made the film with her 12-year-old niece in mind and a desire to break down stereotypes.

Borda, who is stepping down from the New York Phil at the end of the month, has witnessed great strides in her decades as an orchestra manager but still sees work to be done.

“We can’t give up on what we’re doing,” she says. “My hope is that we won’t need these kinds of competitions — these gender- or racial-specific competitions — in the future. I would hope that the world and the worldview become open enough that they’re simply not needed.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.