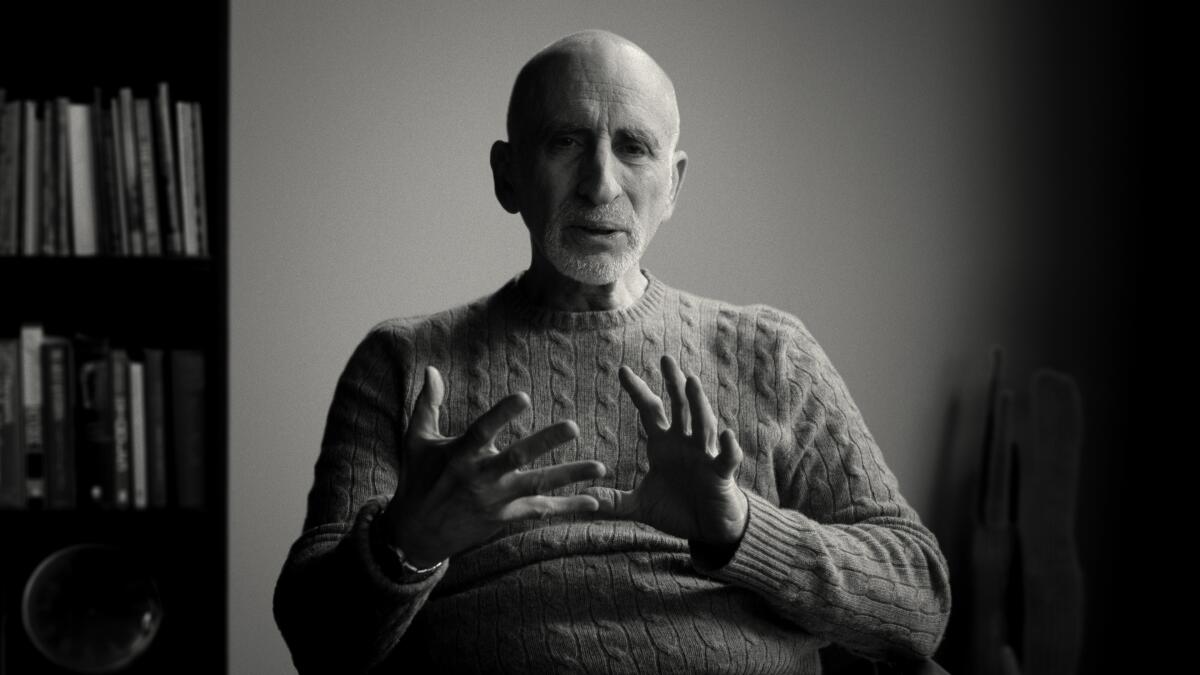

Commentary: A critic does therapy with Phil Stutz, go-to shrink for Jonah Hill and other stars

- Share via

On Sunday morning, while making what I prayed would be a quick run to Target, I received a call from the assistant of Phil Stutz, letting me know that the doctor would be able to see me at 4 p.m. that afternoon.

It’s not every day that the shrink to the stars finds room in his schedule for a plebeian journalist, so I rushed home with my new utensil organizer, ice trays and gigantic package of paper towels and rewatched “Stutz,” the Netflix documentary that Jonah Hill made about his beloved therapist.

Stutz’s name, known for decades among entertainment industry elites, circulated more widely after Dana Goodyear wrote a 2011 New Yorker feature about Stutz’s work and his collaboration with fellow therapist Barry Michels on their book “The Tools: Transform Your Problems Into Courage, Confidence, and Creativity.”

A veteran of psychotherapy, I read the book when it came out in 2012, curious about what the authors call their “spiritual approach to psychology” and wondering if a more action-oriented program might produce results more quickly than my trek through psychoanalysis, which was only just getting started after 12 long years. The book engaged my hopes before it was relegated to a lower bookshelf, where it gathered dust amid a small stack of respectable self-help guides.

Hill’s documentary, which came out in November, lays bare his own insecurities and sorrows, including his feelings about his weight and its impact on his intimate relationships. The raw emotion on display in the film and the loving bond between therapist and patient reignited my interest in Stutz’s practical psychology, which mixes the tough love of life coaching with a secular mysticism that aims to connect a suffering individual to a higher power, however that might be conceived. The film skirts the more ethereal aspects of this work, at least until the end when the good doctor embarks on what looks like a form of astral projection.

Trained as a psychiatrist, with a New York University medical degree, Stutz is a man of science who follows his intuition. His practice pooh-poohs Freudian protocol. Indeed, he developed his theories in reaction to what he felt was the navel-gazing passivity of traditional psychotherapy.

The antithesis of the silent shrink, he punctuates his gruff remarks with profanities, speaks liberally about his own struggles in a defiant New York accent and joshes with his patients as though they were a younger sibling. At one point in the film, Stutz teasingly tells Hill that he’s been intimate with his mother, a comment that might get a more traditional psychoanalyst defrocked. But there’s a method to Stutz’s maverick madness.

When Goodyear wrote her article, subtitled “a cure for blocked screenwriters,” Stutz was seeing patients in his modest apartment in a stucco Westside building that modeled a monastic simplicity for his high-powered Hollywood clientele. Those days are over. He now occupies a luminous lair on a high floor of a gated tower in the Century City area.

His home office, where he regularly saw patients until Zoom took over the world, is elegantly appointed with books, paintings and tasteful furnishings. I took a seat on a leather couch while he settled into one of the chairs opposite me, twisting and turning in unpredictable fashion, the product of his restless energy and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, which he talks about openly in the film.

A coughing fit had him up again, hunting for cough drops while I shriveled in my seat, overtaken by my usual anxieties. I had arrived early at his building and sat for a few minutes in the lobby, using one of his tools to compose myself before meeting him. But I felt extremely self-conscious as we began our conversation, my lifelong stammer growing more cumbersome as I exhorted myself to just relax.

Sensing my discomfort, Stutz sprang into therapeutic action. He threw me a pack of unopened index cards and asked me to unwrap them. He moved beside me on the couch holding a clipboard, and with shaky hands started diagramming essential aspects of his theory that would benefit a case as ostentatious as my own.

Partial to communicating key concepts to his patients through schematics, he drew a circle, then asked me to write inside it the words “I Am.” Then he sketched a moon-like figure that was almost spooning the sphere representing me. Inside this shape he wrote the words “You Are Not.”

“This I Am circle is the definition of who you are,” he explained. “If you let anybody else get inside your head, you’ve lost your identity. You have to protect this.”

The You Are Not shape represents what he calls Part X, the enemy. This destructive force, part of the universe, will never be vanquished. But the obstacles and difficulties it throws up can be framed as catalysts for growth. Stutz thinks of Part X as an ineradicable evil that is always threatening to nullify our being. His work is designed to prevent his patients from falling into the inertia and regression that are the common responses to hardship and unfairness.

OK, but what if the You Are Not energy has gained entry into the I Am sphere and the negativity is coming from inside the house? I posed the question as disinterestedly as possible, but it was clear I wasn’t asking for a friend.

“The visitor has to be expelled,” he said with barely a pause. “And the force that expels the contaminants, that source is rage. Just as if you took a piss on my office, I’d say, ‘Get the [hell] out of here.’ But this isn’t personal rage. It has purpose, which is cleanliness. Getting rid of all the bogeys.”

Psychoanalysts, he said, are helpless to tackle this problem: “Some of them have done good work, but they can’t solve this because they have no plan to admit what the issue is nor do they have any tools to challenge it.”

For Stutz, action, not endless speculation — or what he calls “loose talk” — is the answer.

“In Western culture, the assumption is I have to have a certain level of success in order to feel good about myself, even to feel human, but it’s not true,” he said. “What you have to do is take action before you know who you are. Before you know what’s supposed to happen. If you can do that, then you can become confident.”

My self-deprecating remarks, a knee-jerk reflex with me, didn’t amuse him. “Self-attack is a sin, and it’s an ignorant sin,” he said. “Not because there’s nothing wrong with you. It’s that we don’t attack ourselves for any reason. We just don’t do it, and that’s a law.”

But later he interrupted the discussion for some encouragement: “By the way, you’re doing fantastically well so far, like really well. It’s very heartening.” He pointed out how much clearer my speech had become in just a few minutes. That usually happens when I move out of performance mode into just being mode, but Stutz’s rambunctious concern invited the shift.

What separates Stutz’s system from more gimmicky pop psychology is the idea that the goal isn’t a specific outcome but a commitment to a sustained journey. “Personality is a process,” he argues, something you discover from the steps you take in the world. His existentialist teaching is as much a spiritual education as it is therapeutic endeavor.

What does he call what he does? “I see it as a study and application of the laws of human development, whether you want to call it psychoanalysis, Sunday school or Big Ten track squad,” he said. “It doesn’t matter. And the little things are actually more valuable than the big things, because there are more of them — like times 100.”

The tools are designed to keep a person moving forward in the face of ceaseless challenge, which is humanity’s lot. “The person who needs to understand everything in order for him to assess and improve problem areas, that person is wasting his life, even with a shrink with the best of motivations,” he said.

Why has his work caught on in Hollywood? Joaquin Phoenix and Rooney Mara are among the producers of “Stutz,” and TMZ would no doubt pay a king’s ransom for the files of his celebrity patients. “It’s not what people think,” he said. “What attracts them is that I’m very fast, I’m very intuitive and I’m very practical. It would attract anybody. It’s just that these people have the money and they all know each other.”

The documentary reviews the fundamentals of Stutz’s psychology, but he introduced me to a tool that wasn’t covered. When I was in the lobby of his building, preparing for the interview, he said I would have benefited from his cosmic rage tool. I was all ears.

“I learned this tool from two actresses in New York,” he said. “What they would do when they were nervous on, say, opening nights when there were critics in the house, is that before the show started they’d stand behind the curtain and scream, ‘[Blank] you! Go back to Jersey! I don’t give a [blank] what you think, you piece of [blank].’ And then they would relax and give a credible rendering of what they were trying to do when the curtain went up.”

“So I should have cursed you out when heading up in the elevator?” I asked.

“Some people do it silently, but they radiate rage, and the key of the rage is it’s 360 degrees,” he said. “You try to get yourself in this cosmic rage space and then keep it going.”

The point, I gathered, is to harness our own power by rejecting external definitions of the self. And to see that our actions are stronger than the imagined thoughts of someone else.

He named Carl Jung as a minor influence on his work and Rudolf Steiner as a major influence. Both of these thinkers had an abiding interest in the occult, which Stutz shares. The tools he has developed are said to give the user access to higher forces that he avoids discussing in religious terms, but his psychology has an otherworldly dimension, as the film elliptically touches on near the end when he lies down on a bed and grapples with the haunting legacy of his younger brother’s death in childhood.

How does he feel about the film he spent years making with one of his patients? “I’ll tell you exactly how I feel. Number one — Jonah is going to be a big-time, all-time director. That’s my first conclusion,” he said. “But the second is a little different. I thought I did a good job. I wasn’t spectacular. Jonah was really spectacular. But even he, with his level of insight and courage, wasn’t the highest level of what was going on. The highest level is that God dropped a bomb on Los Angeles. All the truth that came out of the movie wasn’t the result of either of us. It was God dropping on us a tremendous opportunity.”

Noticing that his energy was visibly drained after our intense hour together, I asked if there were any final thoughts he wanted to share before I left.

“No, actually,” he said, unable to resist a teaching moment. “Don’t be in that journalistic mode. Just be humble and do what I’m telling you. And remember, you’re an ignorant [blank]. And that more, more, more is less, less, less.”

“That was fun,” he said, as he accompanied me out of his office. “I don’t think I’ve ever done an interview like that before.”

“Me either,” I replied.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.