When he was 7, Diébédo Francis Kéré left his native village of Gando in Burkina Faso at the insistence of his father so that he might learn to read and write. Gando, about 115 miles southeast of the capital of Ouagadougou, had neither a school nor electricity nor running water, so Kéré headed to Tenkodogo, a nearby provincial capital.

As he recounted in a 2013 TED Talk, Kéré returned home on holidays, and at the end of every visit, he made the rounds to all the village compounds to say his goodbyes. At each stop, the women would tug at a knot in their skirts to reveal a penny tucked into their waistbands — often their last penny — that they’d give him as a parting gift. The pennies were their way of contributing to the boy’s education. By investing in Kéré, they hoped that he might be successful and that he would one day “come back and help improve the quality of life of the community.”

It was a worthwhile investment: Kéré is now an architect, and in 2001, he did indeed return to Gando to build a much-needed elementary school. Crafted from locally made clay bricks, his one-story school not only made the most of filtered light and passive ventilation but the graceful design — a series of rectangular volumes sheltered by a gently curving overhanging roof — also drew the attention of the architectural press.

It was the first of several such education buildings that Kéré designed for Gando, buildings for which he also did the fundraising — at times by cajoling his Berlin architecture school classmates into giving up extra coffee and cigarettes so they might give their spare change to him.

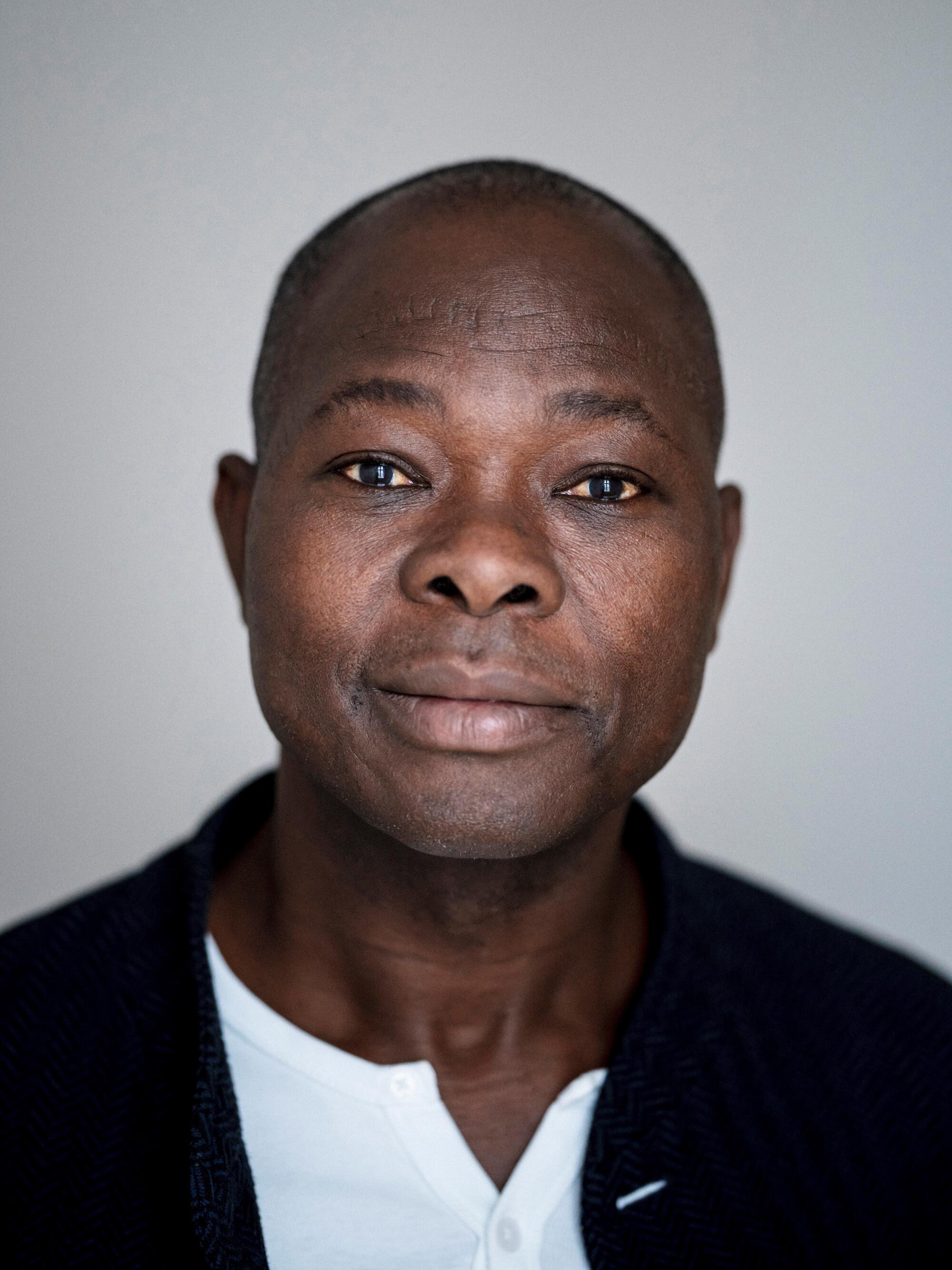

For this work and for other designs in which he has brought together communities to build collectively, Kéré on Tuesday morning was named the 2022 laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

It’s a historic turn for the Pritzkers: Kéré is the first African and the first Black person to win the prize, which, since its inception in 1979, has primarily gone to male architects from Europe, the United States and Asia. “He knows, from within, that architecture is not about the object but the objective; not the product, but the process,” reads the jury’s citation. “Francis Kéré’s work shows us the power of materiality rooted in place.”

The award marks a continued interest in social architecture on behalf of the Pritzker’s jurors. Last year’s winners were French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, founders of the namesake firm Lacaton & Vassal, a duo known less for their form-making than for their surgical revamps of existing designs — such as the expansion of a blocky public housing building in Bordeaux that added windows and patios to once-dim apartment units.

Of his work, Kéré said in a statement: “It is not because you are rich that you should waste material. It is not because you are poor that you should not try to create quality.”

Kéré was born in Burkina Faso in 1965, the son of a traditional village chief in Gando. In 1985, after studying in Burkina Faso, he traveled to Germany on a vocational carpentry scholarship, but ultimately became intrigued by architecture. In the 1990s, he was awarded a scholarship to attend the Technische Universität Berlin, and he completed an advance degree there in 2004. In fact, his design for a primary school in Gando was part of his studies. Recalling the sweltering concrete boxes he studied in as a boy in Tenkodogo, he was determined to devise a building and materials that would work economically and climatologically.

He settled on a method of fortifying clay bricks with cement (which helps protect the structure from the wear of thunderous downpours) and created a floating, double-roof system that allows hot air to rise out of the building and cool air to filter in. Colorful louvered shades allow teachers to direct sunlight into the room depending on the hour of the day. In 2004, the school was the recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Most significantly, the school was built collectively by village members — who helped manufacture the bricks, erect the walls and pound and polish the mud floors. This not only allowed the village to build a new school in a timely and economical fashion but it also taught marketable construction techniques to untrained laborers. “My people can use these skills,” Kéré says during his TED Talk, “to earn money themselves.”

It is a system he has employed in other buildings around Gando, including a teachers’ housing complex, whose curvilinear design was inspired by Burkinabè village compounds, and Naaba Belem Goumma Secondary School, whose first phase was completed in 2011 and whose second phase is currently under construction.

Kéré, who divides his time between Burkina Faso and Germany, where he runs a small namesake studio, also has more high-profile projects to his credit. These include his design for the Serpentine Pavilion at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 2017; he was the first African architect to create a pavilion in the design series’ history. On that occasion, he designed a circular, wood roof structure that hovered over curving blue walls punctured by a triangular pattern. Its form is evocative of a council tree, where gatherings are held in traditional villages.

“The tree was always the most important place in my village,” Kéré told the Guardian’s Oliver Wainwright on that occasion. “It is where people come together under the shade of its branches to discuss, a place to decide matters, about love, about life. I want the pavilion to serve the same function: a simple open shelter to create a sense of freedom and community.”

In the United States, Kéré designed a temporary installation of a dozen colorful towers — evocative of textiles — for the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio, Calif., in 2019. That same year, he created a 2,100-square-foot pavilion for the Tippet Rise Art Center in Montana. Of the latter project, architecture writer Justin Davidson described the piece — made from dead trees that had been harvested from nearby forests — as evoking “an upside-down topography reminiscent of the hills all around.”

In addition to the social and economic aspects of his work, Kéré’s interest in sustainable building materials and passive ventilation nods to the realities of climate change — and a future in which overtaxed mechanical heating and ventilation systems will have to give way to more passive methods of cooling and heating.

As he says in his statement responding to his Pritzker win: “We are interlinked and concerns in climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all.”

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal take architecture’s top honor for work that includes the Palais de Tokyo rehab and social housing preservation

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.