When Daddy Yankee showed up at a Montebello gas station to hype his infectious hit “Gasolina,” the Puerto Rican recording star drew so many fans he couldn’t get out of the limo. That was the moment it hit local music publicist Ximena Acosta: Reggaeton was here to stay.

“I’m never going to forget. I had a chunk of my hair pulled out it was so bad,” Acosta recalls in the buzzworthy Spotify podcast “Loud: The History of Reggaeton.” “We tried taking him out of the limo a few times, and we just — we couldn’t. And I had that feeling in my gut of, ‘Oh, my God, this is gigantic.’”

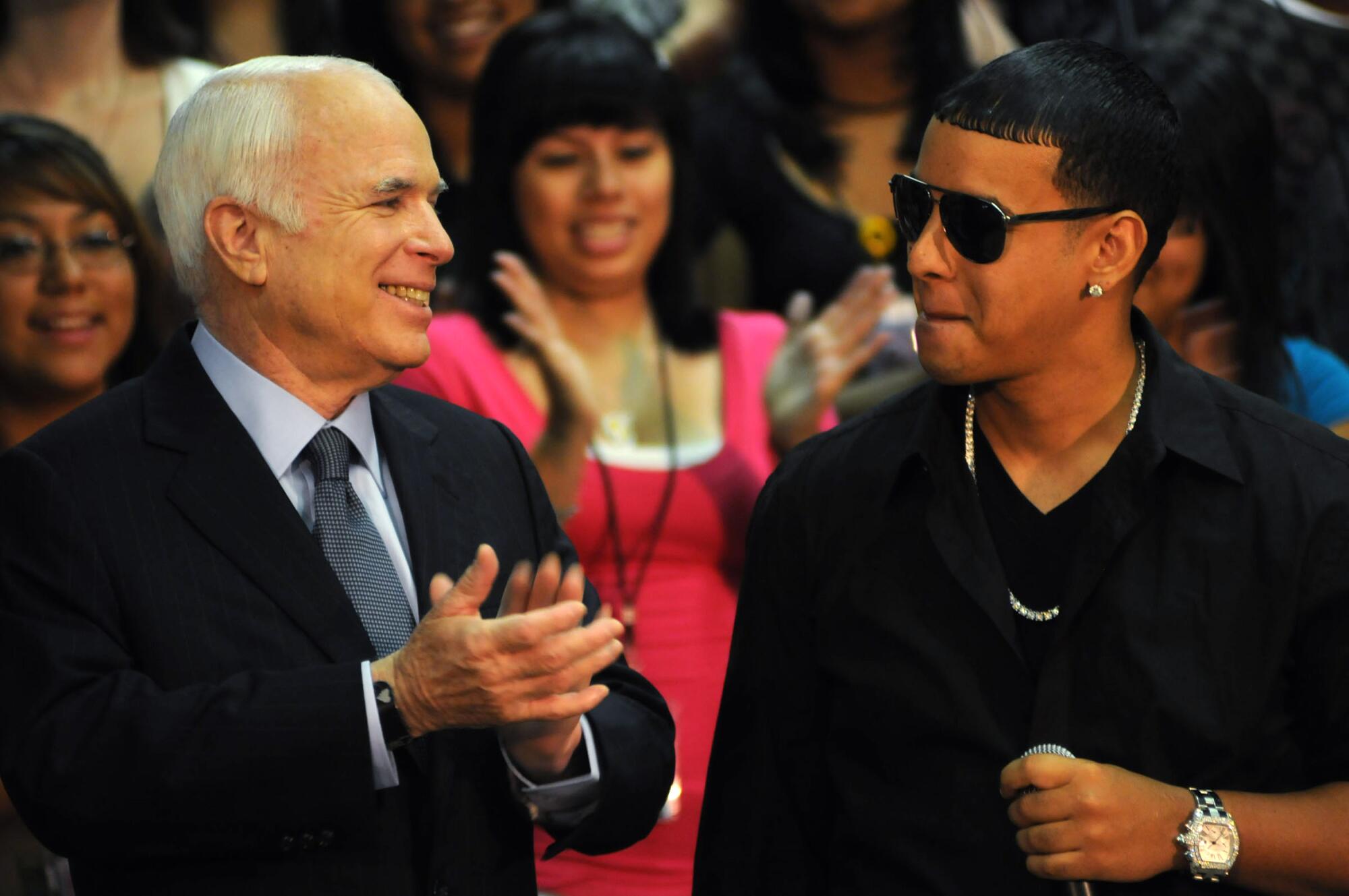

It was the mid-2000s, and Daddy Yankee, who had never been to Los Angeles, was pushing his 2004 breakout album, “Barrio Fino.” “He plays for the Yankees?” Acosta remembers a local TV news station asking in response to her pitch.

But the streets of Los Angeles were well aware of Daddy Yankee and the sound of reggaeton, which naysayers at the time called a passing fad. After Daddy Yankee was trailed across East L.A. until he stopped at a taqueria, Acosta in the podcast recalls turning on the radio to a new soundscape. “Power 106 was playing Don Omar, Super Estrella was playing Daddy Yankee, KIIS FM was playing Ivy Queen, and I was like ..., ‘This s— is here to stay.’ This was going to completely, completely change the landscape of music.”

It is a thrilling recollection in the middle of a deeply researched production by Spotify Originals and Futuro Studios. “Loud,” which comes out with its 10th and final episode this week, has arguably set a new standard in Latin music-focused historical cultural podcasts, after this year’s WBUR hit “Anything for Selena.” It’s also breaking ground in its use of Spanish and Spanglish as the de facto lingua of the show, and the inspired choice of reggaeton original Ivy Queen as its host.

The podcast charts the journey of this amalgamation of musical influences in a direct line from Jamaica to Panama to New York to Puerto Rico, where it boomed, and now to Colombia and the world.

Featuring a track with Skrillex, Jhay Cortez’s expansive sophomore album builds on the success of his global hits with Bad Bunny and J Balvin.

A listener can hear Ivy Queen, a strong female leader in a male-dominated subculture, barely containing her wonderment at the global acceptance of the genre that was once the subject of censorship, police crackdowns and political persecutions. It’s all detailed in the series.

“I still remember the first time I got paid to rap, it was like $500, y yo pensé que quinientos pesos era un millions of dollars, you know!” Ivy Queen recalls in the 10th episode.

“Tantas cosas han pasado, so much has happened. And look at reggaeton now!” the host says. “It kind of makes me ask myself, what is it that reggaeton has given to the world? What is our legacy?”

Well, the 2017 reggaeton remix of the Luis Fonsi track “Despacito,” featuring Daddy Yankee and written by Erika Ender, became the most viewed video in YouTube history and has notched more than 7.5 billion plays. Today Bad Bunny is making commercials for McDonalds and Cheetos and was the most streamed artist on Spotify in 2020.

Listening to “Loud,” I was struck by the realization that one of the uglier footnotes to the history of reggaeton is that many people who now swoon over its reach probably disliked it when they first heard it.

To many ears in the early 2000s, reggaeton sounded somehow uncouth or vulgar. Lyrics were definitely not safe for work and artists who were club favorites were often said to be tied to the drug trade or to be overtly objectifying women. Many people with whom I otherwise shared plenty of cultural touchstones scoffed or simply said they hated it.

Bad Bunny may be the ultimate 21st-century global superstar: a bilingual singer, rapper and style icon with progressive social views who releases songs whenever he wants.

Not surprisingly, institutional respect was hard to come by. Even today, artists complain that the Latin Recording Academy puts reggaeton in its “urban” categories, using what many see as a term of exclusion and segregation. Latin Grammy wins in major categories have been rare for reggaeton stars. This year, artist J Balvin is calling for a boycott of the awards, two years after he and Daddy Yankee were no-shows at the 2019 ceremony following a social media campaign with the phrase “Without reggaeton, there’s no Latin Grammys.”

“These gatekeepers of what proper music is, whether they were in journalism or cultural institutions, had many objections,” including the claim that the reggaeton delivery style did not qualify as “singing,” says Raquel Z. Rivera, one of the earliest writers on reggaeton. “It was an aesthetically conservative argument. People dance to it, and you refuse to call it music?

“Then, to top it off,” she adds, “there was the prejudice that people always have toward music genres if they’re produced by young Black people from lower income communities.”

I loved reggaeton from the second I first heard it. It had an aggressive, very Latin bass line and somehow the music always sounded significantly better played, yes, loud, across FM radio or through subwoofers. It made me want to dance. What’s not to like?

When reggaeton really began to take hold locally, the city had already shifted to a majority-youth brown metropolis. In that sense, it sounded like popular music aimed primarily at urban immigrant young people, as opposed to, say, middle-class rockers from the outer cities, whose tastes have long defined the boundaries of youth popular culture.

Reggaeton star Karol G just turned 30, released her much-anticipated new album “KG0516” and parried rumors of a breakup with rapper Anuel AA.

The once-total dominance of Mexican regional genres in L.A. now had a formidable competitor for young people’s attention.

And in the early days it was everywhere. Literally, every car stuck in lanes around me in South or East L.A., or cruising past in the other direction, was loudly playing Tego Calderon or Ivy Queen, la reina del sonido urbano. On Broadway or Central Avenue, streams of two-color fliers announcing shows at immigrant dance halls crowded all the available space on light posts.

In 2005, the station 96.3-FM moved to a full-time Latin urban format, giving reggaeton a permanent home on the L.A. airwaves that remains a leader to this day in a robust local market.

The Ivy Queen posters stood out. To the L.A. Latin queer community, Ivy Queen was an underground goddess. Her sharp features and deeper alto voice made some fans (and haters) assume she was transgender, which Ivy Queen acknowledges, but also, who cared? How could you not dance even a little bit to her 2003 banger “Yo Quiero Bailar”?

“It goes to your ear and once you’re moving, that’s it, it’s done, you’re trapped,” Ivy Queen says with a big laugh in a recent interview with The Times.

Reached via video conference at her studio in Miami, Ivy Queen calls L.A. one of her favorite places, a city that any hungry artist must conquer in order to go massive. Look at it: Nearly half the population is Latino and nearly a third of it is between 15 and 34. No wonder it had a part in catapulting reggaeton to the U.S. mainstream.

“We have a lot of mexicanos, hondureños, salvadoreños coming to our shows,” she says of her L.A. performances. “Cada show que vamos hacer todavía ponen los posters en las luces en la calle, and yo, that’s an OG movement, that’s retro, that’s how you do the promo!”

The podcast project for Ivy Queen has been “an emotional roller coaster” that involved confronting her personal history and the challenging histories of some of her fellow trailblazers in the movement.

From the beginning, she wanted the production to remain true to the players, the roots, as well as the language that united it all. “I asked Spotify [if] I could please maintain my essence and do my little Spanglish,” Ivy Queen says. “Because I’m talking about the history of reggaeton and the whole movement is in Spanish. This music belongs to the Latinos, you know?”

More than a hundred interviews were conducted for the podcast, and Spotify and Futuro Studios hired some of the most experienced and respected field producers around. The production also emphasized hiring female talent and engineers.

“The reggaeton story had never really been told in a comprehensive way before, and we wanted to treat it with the same respect that any other great music had been told, whether it was jazz or hip-hop,” says Marlon Bishop, executive producer of Futuro Studios.

The response has been overwhelmingly positive, according to Spotify executives. “I had high expectations, and they delivered,” says journalist Rivera.

With the dancing style of perreo — think Latin twerking — embraced by younger generations that did not experience the reggaeton backlash, it’s nice to hear Ivy Queen reflect on how far the music has come, especially for women and queer artists.

After all, change is constant.

“I just hope that we don’t lose the essence, que no la perdamos,” the artist says. “We see a lot of blend. Now it’s the pop reggaeton era, using all those drum patterns that reggaeton has. I’m an OG. I need that beat to hit hard. I know music is supposed to evolucionar, but I hope we don’t lose the true meaning of the lucha that we did.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.