Column: Who will fill Eli Broad’s philanthropic shoes? How about nobody?

- Share via

Every February, writer and cultural critic William Poundstone publishes a post he calls “Groundhog Day” on his perceptive and affable blog, Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, which looks at how Los Angeles has historically been described in the media.

The annual aggregation of quotes — culled from six decades of cheese-puff reports about the city — often reads like variations on a theme: basically, that Los Angeles was a vast cultural wasteland, but that the arrival of some new museum/gallery/concert hall/art fair may finally transform this land of woo-woo starlet surferheads into the sort of cultural destination that the literati needn’t be quite so embarrassed about visiting.

Eli Broad envisioned Grand Avenue as DTLA’s Champs-Élysées. Instead it may be a memorial to an urbanism of big gestures that is passing into history.

Sample entry: “Los Angeles is a place where desire, fantasy and commerce come together, yet contemporary art has traditionally been overshadowed by the star power of Hollywood. Still, the city has quietly emerged as an important contemporary art hub.” That was courtesy of the New York Times in 2018.

It pairs well with the following Life magazine quote from 1966: “For 20 years Los Angeles had been a kind of national joke. ... Then, one day in the 1950s, that huge humming, uncorseted, uninhabitable town woke up to discover it was turning into the cultural capital of the West.”

No matter the decade, Poundstone’s wry aggregations capture a view of Los Angeles as a place that is always arriving yet never quite lands.

I was thinking about these zombie tropes as I read the latest New York Times assessment of the state of culture in Los Angeles.

The piece noted that the city “had established itself as a cultural capital with its galaxy of museums, galleries and performing arts institutions, defying dated stereotypes of a superficial Hollywood with little interest in art.” But “it now confronts uncertainty across its cultural landscape” with the one-two punch of the pandemic and the death of philanthropist Eli Broad.

Like an overstuffed suitcase, there is lots to unpack — beginning with the idea that L.A. has finally (finally) achieved cultural capital status and ending with the intimation that the city’s art scene might wither without the presence of a strong philanthropist à la Broad.

Let’s start with the question of philanthropy.

The New York Times’ story, written by Adam Nagourney, implies that fundraising in celebrity-obsessed Tinseltown can be an exercise in frustration. “For all its wealth,” he writes, “Los Angeles has always been a challenging fund-raising environment.”

It’s an echo of a piece about Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Times that Nagourney co-authored with Tim Arango in 2018. “For all its successes,” they wrote, “Los Angeles has not developed the political, cultural and philanthropic institutions that have proved critical in other American cities.”

They also fret over Broad’s impending retirement.

Neither story mentions the Getty Foundation, a local institution that is not only endowed to the teeth but has supported innovative cultural initiatives over more than a decade, such as the Pacific Standard Time series of exhibitions, as well as various pandemic recovery efforts.

Beyond that, the woe-is-me-where-are-the-Los-Angeles-philanthropists narrative doesn’t appear to be entirely grounded in fact.

The 2018 New York Times story notes that Los Angeles ranked 14th in charitable giving according to a 2017 metro market study by Charity Navigator (a ranking that also took into account issues such as accountability and transparency). What it fails to mention is that this placed L.A. five spots ahead of New York, which came in 19th out of 30 metro areas analyzed. I repeat, five spots ahead of New York. The No. 1 city that year? San Diego.

Los Angeles also came out toward the top when it came to median total contributions. The national average, according to the report, was $2.9 million. Median total contributions in L.A. came to more than $4 million — well above average, and above New York, which checked in at almost $3.9 million.

A separate study, published that same year by the Chronicle of Philanthropy, showed that giving ratios in Los Angeles edged out those of New York: 2.9% to 2.8%. (A giving ratio measures a city’s charitable contributions as a share of total adjusted gross income.)

To be fair, New York patrons gave a slightly higher proportion of their dollars to arts and culture causes than L.A. patrons — 18% to 15.2%, according to Charity Navigator. But the overall numbers hardly paint a picture of Los Angeles as disengaged from the civic act of giving.

So can we put this tired argument to rest?

And while we’re at it, let’s retire the outmoded idea that the most important factor in a city’s cultural landscape is the presence of some white knight bearing a checkbook and grandiose ideas about turning bulldozed Los Angeles neighborhoods into the Champs-Élysées (as Broad once described his vision for Bunker Hill).

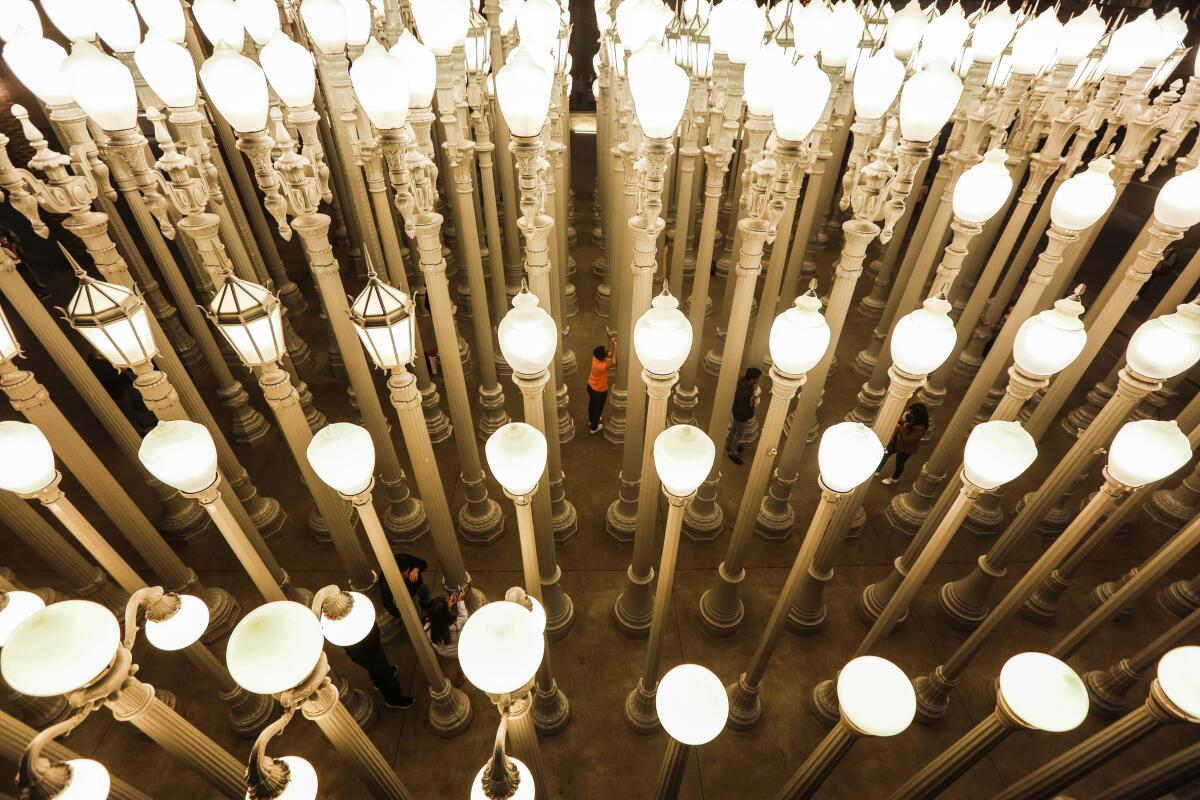

In fact, a moneyed philanthropist can wreak havoc on public institutions. Like the time, in 2008, when, after financing the construction of the Renzo Piano-designed Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to the tune of $50 million, Broad announced, weeks before the museum’s opening, that he wouldn’t be giving LACMA his collection.

Two years later, LACMA alleged that Broad had left the museum holding the bag on $5.5 million in additional construction costs — something a spokesperson for Broad denied. He also left the museum with additional maintenance expenses, since he didn’t endow the building. As the late LACMA director Andrea Rich told the New Yorker in 2010: Broad once told her that no one is remembered for funding endowments. In 2015, he opened his own museum, the Broad downtown.

Given this history, and given all the discussions about equity in culture that have taken place over the past year, it’s a weird time for the New York Times to be pondering who should fill the role of L.A.’s next Daddy Warbucks.

We are at a moment in which the role of mega-donors — and the ways in which they wield their money and their power — has come under increasing scrutiny.

In the museum sector, this has led to heightened activism over the source of board member wealth.

Prominent businessmen — such as Warren B. Kanders at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and Tom Gores at LACMA — have been pressed to resign from museum board positions over questions relating to the source of their wealth. (Kanders owned a defense manufacturer that fabricated tear-gas grenades employed on migrant families at the U.S.-Mexico border; Gores ran a prison phone service that charged exorbitant fees to largely poor and nonwhite inmates or their families.)

We are also at a moment in which there have been greater calls for public support of the arts.

My colleague, Times classical music critic Mark Swed, has called for a federal Secretary of Culture. Los Angeles critic and scholar David Kipen, who once served as literature director at the National Endowment for the Arts, has proposed a Federal Writers Project inspired by the Roosevelt-era Works Progress Administration. That idea is now a bill, sponsored by U.S. Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance).

Much more than simply increasing diversity, the task ahead will consist of rethinking the very ways in which museums are governed.

President Biden says he wants to boost the budgets of the NEA and the National Endowment for the Humanities. (The proposed $33.5 million increase to the NEA would bring that agency’s budget to $201 million — its highest level funding since its founding in 1965.)

After our destabilizing pandemic year, greater public funding is critical for arts organizations across the country, which frequently find themselves beholden to the whims of impetuous donors. (Benefactors are renowned for supporting grand building projects upon which they can bestow their names; they are generally less interested in raising funds to, say, pay equitable wages to frontline and entry-level staff.)

If government support for the arts in the United States seems totally pie-in-the-sky, it is not — especially at the local level.

LACMA draws an annual subsidy from L.A. County taxpayers of about $25 million — an amount that represents a quarter to a fifth of its annual budget. In Michigan, a $15 annual tax on residential properties valued at $150,000 in three counties goes toward funding the Detroit Institute of the Arts. In Colorado, a tiny portion of the sales tax (1 cent on every $10 in sales and use tax) is set aside to fund cultural and scientific institutions in a seven-county tax district around Denver.

“It’s a stable source of funding that doesn’t fluctuate like philanthropy,” says Michael Rushton, a professor in the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, “and you can make sure it’s being evenly distributed.”

It’s not European levels of funding, but these models exist and have been proven to work in the U.S. It is this model we should push for in Los Angeles — not more Eli Broads.

Which brings me to the second point in the New York Times report: the idea that L.A. has at last, finally — FINALMENTE! (in melodramatic telenovela voice) — reached that mythical status of “global cultural capital.”

Go figure, I think Southern California has been pretty international for a while now.

Yes, there’s the film industry — which has been exporting culture for more than a century. And there have been so many art, architecture, music, stage and literary movements and influential creators born in L.A. that it’s pointless to name them all.

There are other currents, too. In the early 20th century, the Mexican Revolution was planned, in part, in Los Angeles. During that same period, Korean independence activist Ahn Chang-Ho was inspired by organizing among Korean immigrants in agricultural communities such as Riverside. It was a period living in Los Angeles that helped shape the worldview of Mexican essayist and Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz. In Tokyo, there is a budding lowrider scene inspired by Chicano youth.

Not to mention the traffic of goods: For the last two decades, the Port of Los Angeles has been the busiest container port in the Western Hemisphere.

A philanthropist building a namesake museum on Bunker Hill is significant, but it’s not what makes L.A. important. That lies in a more unquantifiable realm having to do with ideas and the ways in which they are transmitted. For that we don’t need a great patron. We need better public institutions — ones that serve everybody, not just the people who fund them.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.