Chanel Miller on her art debut: I never thought I’d have so much space to be seen

- Share via

News media first introduced artist and writer Chanel Miller to the world as Emily Doe: the woman in sexual assault case People of the State of California v. Brock Allen Turner, discovered unconscious behind a dumpster at Stanford University.

Miller read her powerful 12-page victim impact statement at Turner’s sentencing in June 2016, exploding with viral fame thanks to Buzzfeed, where 11 million people read her statement in just four days. Newspapers reprinted it. Eighteen members of the House joined forces to read it on the floor of Congress. Emily Doe became an anonymous hero of sexual assault survivors, and nobody knew who she was.

Not until September 2019 did Miller go public, reclaiming her identity by publishing the aptly titled “Know My Name,” a bestselling memoir about her experiences before, during and after the trial. That process takes another step forward this month in San Francisco, where the Asian Art Museum has opened her first art exhibition in a new wing designed by Culver City architect Kulapat Yantrasast.

Miller is a lifelong illustrator. As a child, she would spend hours drawing on poster board. Miller’s mother, who worked at an art framing store in the ‘90s, would showcase young Chanel’s works over the fireplace, “which provided a sense of legitimacy from a very young age,” Miller said from her apartment in New York, where she moved this year. “On my physics tests when I didn’t know the answer, I would draw a guy shrugging. It would be really intricate, shaded in with graphite. I wanted to show the teacher that I did have a skill, even if it didn’t align with what they were teaching.”

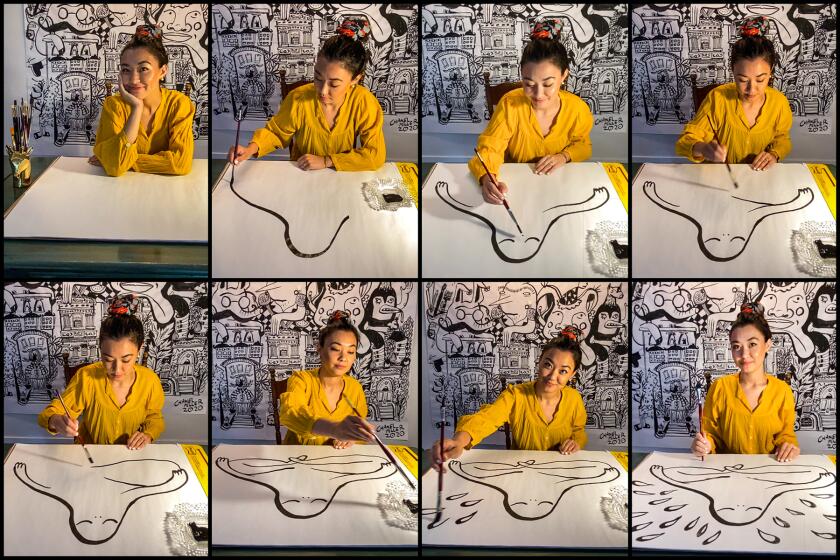

Times photographer Jay L. Clendenin worked with artist Chanel Miller to arrange a socially distances shoot — with him in L.A. and Miller in New York.

When it came time to shed her Emily Doe pseudonym and announce publication of her book, Miller did so by posting her animation to Instagram. Over the subsequent weeks and months, she filled her feed with humanoid figures, simply drawn in black marker. It was these illustrations that eventually caught the attention of Abby Chen, head of contemporary art at the Asian Art Museum.

“Of course I knew about Emily Doe from a few years ago when the Stanford assault case came into the media, but nobody knew who she was,” Chen said. “When I saw her animation and learned she always wanted to be a children’s book writer, that changed things. I became determined to work with her.”

The artist has spoken in interviews about how her mother, the writer May May Miller (pen name Ci Zhang), emigrated from China and inspired in her daughter the will to challenge oppression. Late last year, Chen invited Chanel Miller to the Asian Art Museum to view her portfolio and to brainstorm a collaboration. The project was supposed to coincide with the opening of the museum’s 28,000-square-foot Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang Pavilion.

Chanel Miller discusses her first major exhibition, a mural at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

When Chen walked Miller through the construction site, it soon became apparent that the artist’s pared-back, approachable illustrations could be suitable for a large format — and not just any large format, but the entire length of a sweeping gallery with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Hyde Street.

Miller’s resulting work, titled “I was, I am, I will be,” is a 70-by-13-foot vinyl mural depicting a figure in three vignettes: first, curled in the fetal position in a pool of tears; second, sitting up in meditation, the tears sublimating into an aura of energy; third, rising to its feet and walking forward.

“It’s not meant to be read in a linear way,” Miller said. “I like that the character begins in a reclined position, then gets into an onward position, but just as quickly, you may find yourself returning to phase one of that narrative.”

When Chen commissioned the work, neither she nor Miller foresaw how COVID-19 would shake the museum, the city and the world. Even with the museum closed, the installation of Miller’s message of healing in a gallery visible from the street has become strangely prescient — an instance of a piece transcending its moment that Chen has seen only a few times in her career.

“When we began, it was more about her statement as an artist, but now with COVID it’s really become a story about all of us,” Chen said. “Chanel from the beginning was adamant that the work speak to people at large.”

Architect Yantrasast — whose design credits include the Marciano Art Foundation in L.A., the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan and the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Ky. — said Miller’s mural expresses the precise reason he created this gallery space. Experiencing a museum work from the street creates a dialogue between exclusivity and democracy; the art speaks to the role that museums play in civic life, even when a pandemic dictates they remain closed.

“More and more the reason museums are not relevant is because they don’t connect to their city and to everyday life like they should,” Yantrasast said. “Museums have a big role to play when we need human connection, understanding and empathy. Museum architecture itself should be that connector between people inside the museum and outside. We need another paradigm beyond the white cube.”

Chanel Miller has identified herself as “Emily Doe,” who was sexually assaulted by swimmer Brock Turner at Stanford. Her new memoir, “Know My Name,” is an anguished chronicle of the aftermath of the attack.

So while there was no splashy opening party, Miller’s first museum exhibition — her first exhibition at all, really — lands with a poignant note of emotional resonance. Her work conveys her vision of catharsis that is neither tidy nor linear, but rather nebulous and cyclical. We progress, we revert — radical acceptance, as a therapist might call it.

“The ability to sit with uncertainty is something we’re all learning right now because we have to,” she said. “It’s about how to nourish ourselves with what we have and where we are.”

Miller’s most important takeaway, however, was the scale and magnitude with which people such as Chen see her message.

“They gave me so much freedom to unleash my mind on this real estate,” Miller said. “It’s half a block of the city. I would have never thought to ask for that much space to be seen. I didn’t know it was possible. Moving forward, I know I can ask for even bigger walls.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.