Review: Hank Willis Thomas, Tomashi Jackson and a different kind of color theory

- Share via

Zora Neale Hurston once wrote, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” In other words, context matters.

Two art exhibitions make this case in relation to race, history and, interestingly, color theory, or the study of the interaction and perception of colors. Through this lens, both shows proffer an unexpected model for thinking about race and representation.

In “An All Colored Cast” at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Hank Willis Thomas looks at the representation of people of color in old Hollywood. In “Forever My Lady” at Night Gallery, Tomashi Jackson leads a more freewheeling exploration of the intertwined histories of race and another kind of representation: voting.

Thomas’ show has eight austere wall pieces featuring flat fields of color, often laid out like a TV color bar test pattern. At first glance, they look like run-of-the-mill Minimalist or color field paintings, composed of solid, hard-edged squares or stripes of bright, saturated color.

Closer inspection reveals barely perceptible photographic imagery printed over the smooth, somewhat reflective vinyl. It’s impossible to see these images all at once: You must shift position continuously for the pictures to appear. (They reveal themselves more clearly in flash photography, but that’s not how they appear in the gallery.)

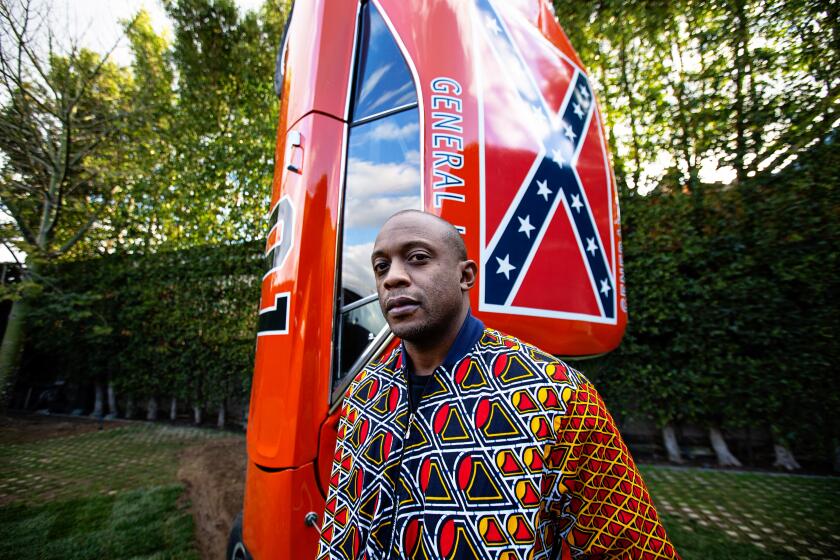

“Easy Rider’s” chopper “Captain America” got trashed too. Hank Willis Thomas crunches history, race and Hollywood tropes in his first solo show in L.A.

The photographic images come from the history of film and television, in particular productions that featured performers of color. “Sundown (Color Bar)” resembles the familiar TV test pattern most closely. Printed across it is a still from the 1941 film “Sundown,” in which white actress Gene Tierney reclines next to a black woman, played by Jeni Le Gon, seated nearby.

The composition is reminiscent of Edouard Manet’s 1863 painting “Olympia,” featuring a reclining white woman attended by a black maid. In Manet’s image, the maid’s skin is so dark that it nearly blends into the background. The entirety of Thomas’ image is similarly hard to see. His use of the color bar refers to calibrating color on the screen, which helps determine what and who is visible.

“‘C’est si bon’ (Le Harmonie del Colore)” refers more directly to color theory, specifically the work of Italian artist Augusto Garau. It encloses two adjoining rectangles in different shades of orange with two different shades of blue. Garau was interested in the relativity of color, how the same hue could look different depending on what was next to it. Printed over these contrasting colors is a still from the 1958 film “Anna Lucasta,” in which characters played by Sammy Davis Jr. and Eartha Kitt face off. In juxtaposing this film, featuring an all-black cast, with Garau’s experiments in relative color, Thomas suggests how viewers might see black people differently when they are the main characters rather than merely servants or background players.

Jackson uses a similar geometric motif in her painting “Girls Time (Heartbreak Hotel).” Typical of her works, the complex image is built up in layers of printed and painted paper, vinyl and fabric, draped delicately atop a wooden frame that extends at a slight angle from the wall.

The imagery, drawn from political publications and signage as well as archival and family photographs, is dense, cacophonous and overlapping to the point of incoherence. Yet clearly at the center is a hot pink vertical rectangle framed by two more rectangles in different shades of yellow. It’s reminiscent of the concentric compositions of German émigré artist Josef Albers in which he mapped out vibrating gradations of color.

Jackson’s use of color theory, while it certainly refers to the stratifications of race, also refers to political colors. Reds and blues dominate the 10 three-dimensional works on view at Night Gallery. (There are also three video works.) The colors, of course, refer to the dominant political parties in the U.S. Yet surprisingly, interspersed with her references to domestic history — the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the CIA’s involvement in the crack cocaine epidemic, the rise of gerrymandering — are election ballots and design motifs from Greece. Several of the pieces are framed with striped borders reminiscent of the labyrinthine Greek meander pattern.

During a recent residency in Athens, Jackson became interested in Greece as the birthplace of democracy, tracing how the right to vote has expanded slowly and often painfully across time and geography. The paintings don’t always tell this story clearly, but a video, “We’re All Gonna Go (Greeks on Sadness, Happiness, and Liberation),” brings these issues together more succinctly.

The video portrays Jackson as her alter ego, R&B crooner Tommy Tonight, lip syncing to Curtis Mayfield’s 1970 song “(Don’t Worry) If There’s Hell Below We’re All Gonna Go.” He cavorts on an Athens rooftop with Greek artist Eleni Mylonas, who is wearing a military-style jacket and a headpiece adorned with a tiny Statue of Liberty.

The video brings otherwise odd bedfellows together in a bit of fun, knitting together concerns about democracy, civil rights and gender through the lens of pop culture. Unlike the paintings, which at times feel overwhelmed by complexity, the video feels frankly hopeful and inclusive.

Also impressive is the inclusiveness of the Thomas show’s eponymous work “An All Colored Cast.” This image is a large, horizontal grid of multicolored squares, each featuring a barely perceptible portrait of a performer of color from Hollywood history. Although the other works in the show focus on representations of black people, here Thomas has broadened the view to include performers of other backgrounds, from well-known celebrities like Desi Arnaz, Anthony Quinn and Anna May Wong, to more obscure actors like Gloria Fong, Jay Silverheels and Lupe Velez. It’s quite moving to walk slowly back and forth, watching their faces flicker in and out of view. It’s like they’re whispering: We were here.

Both Thomas and Jackson demonstrate how a change in perspective can make representation, well, more representative, whether in Hollywood or in real life.

Hank Willis Thomas and Tomashi Jackson

Hank Willis Thomas

Where: Kayne Griffin Corcoran, 1201 S. La Brea Ave., L.A.

When: Tuesdays-Saturdays, through March 7

Info: (310) 586-6886, www.kaynegriffincorcoran.com

Tomashi Jackson

Where: Night Gallery, 2276 E. 16th St., L.A.

When: Through Saturday

Info: (323) 589-1135, www.nightgallery.ca

Support our continuing coverage of L.A.’s art scene. Become a digital subscriber.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.