Column: How Joe Stern made Hollywood’s Matrix Theater dramatically diverse

- Share via

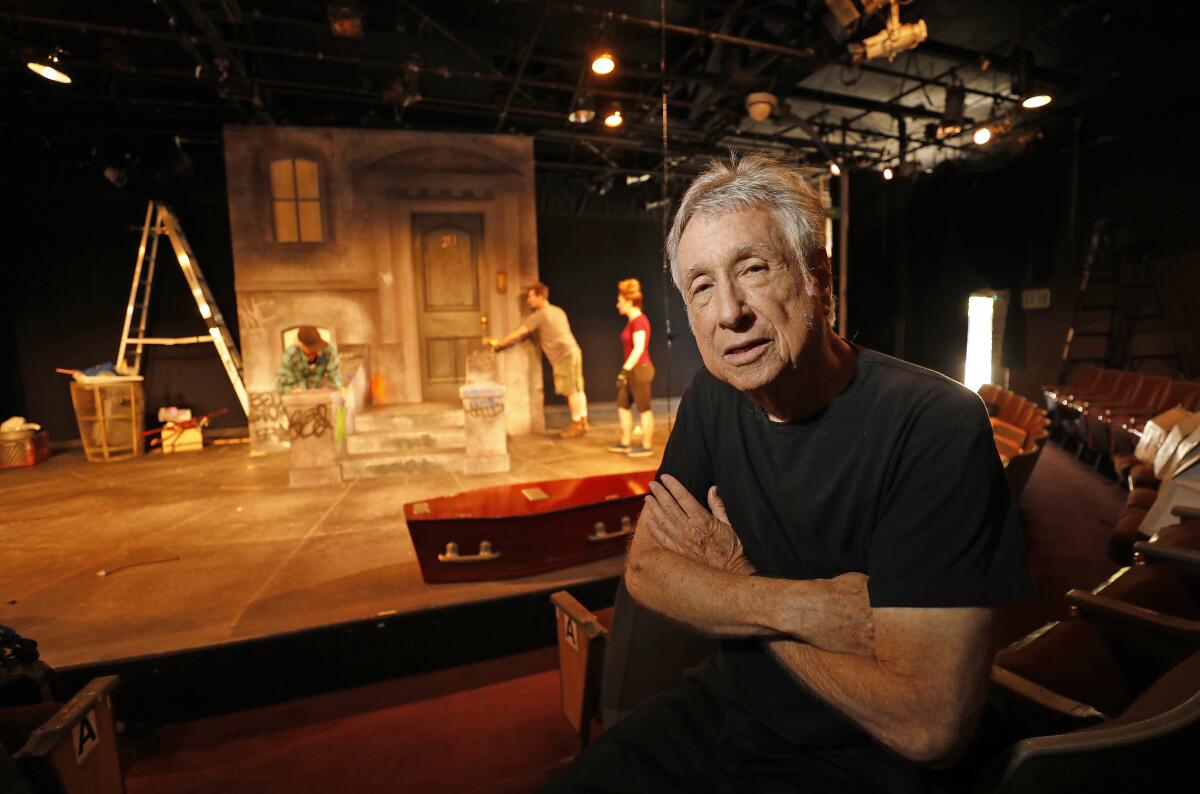

At the Matrix Theater in Hollywood, Joe Stern’s latest revolution is just hitting its stride.

Geraldine Inoa’s “Scraps” recently ended, to be followed, a month later, by Carole Eglash-Kosoff’s “The Double V.” “Scraps,” which Times critic Charles McNulty recently called an example of “a spectacularly vibrant era in African American playwriting,” is a raging unconventionally constructed tragedy in which young New Yorkers are both inured to police brutality and undone by the shooting of their friend by a white cop. “The Double V” is a new play examining how a 1942 letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, asking whether black men should be asked to fight for a country that considers them “half-American,” sparked the Double V campaign and, many believe, the civil rights movement.

Not the kind of plays one might think would show up in a 99-seat theater owned by a self-described old white guy.

For almost 40 years, Stern has been a main character in L.A.’s small-theater world, a beacon to many, an irritant to some. An L.A. native turned New York actor and Hollywood producer, he bought the Matrix in 1977, when few 99-seat theaters even existed in Los Angeles.

Famous for a hands-on approach that irked more than a few directors, he invented a double-casting system, now used at other L.A. theaters, to give actors the flexibility to work onstage while still pursuing careers in film and television. For more than three decades, he has been wildly outspoken in the Equity-waiver fight, arguing, albeit in the end unsuccessfully, that 99-seat theaters need to have the actor-union rates waived in order to survive.

Depending on who’s doing the describing, he is considered a stalwart protector or a self-appointed spokesman for the small-theater scene that still struggles in this town. At 79, with no signs of slowing down, he is most certainly resolute.

Ten years ago, Stern set in motion a change that is more revolutionary than anything he had done before.

He decided that theater — his own and others — needed to be doing a better job talking about race. Although he had been, he says, outspoken about upending stereotypes and increasing diversity on television, he realized he was still “busy doing Pinter” on the stage.

“I realized that I wanted to deal only with race,” says Stern. “I thought it was the most important issue and I was dealing with it in every other part of my life but not in my plays.”

When he told members of the Matrix Theater Company that “everything was going to change,” there was some pushback. People were concerned about political correctness, about losing the audience they had built. Stern says he didn’t want to come off as “some great white father,” but he asked the people he worked with what they saw when they looked at their audiences. “How many people of color do you see? How do we heal the divisions in this country if we aren’t [experiencing things] with each other, listening to each other?”

He also knew that if theaters wanted young audiences to come, they were going to have to do more plays addressing issues that young people care about.

Since 2009, he and his company have put on seven plays with various racial themes, including Lydia Diamond’s “Stick Fly,” Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ “Neighbors,” a multicultural rendition of Arthur Miller’s “All My Sons” and Katori Hall’s “The Mountaintop.” And if one of the last night’s of “Scraps” is any indication, Stern’s desire to build a more diverse audience has been fulfilled.

“The audience at the Matrix is much more mixed than in other theaters, not just racially but age, income, everything,” said Michael Arabian, who is directing “The Double V.” “There is no doubt about it.”

Originally, Stern envisioned the plays as a series people would experience as a whole, but even the most dedicated audience would have a hard time considering a string of semiannual plays a series. His vision, however, soon made itself felt and other producers with similar desires began coming to the Matrix. A few years ago, actress Sophina Brown, realizing that far too many of her colleagues were unfamiliar with the works of August Wilson, staged a reading at her home that was so successful, and emotionally explosive, she decided to try to stage every play in the Wilson canon. She took her decision to Stern.

“I loved his heart, I loved his mission,” she says. “He has always been very passionate about it, and he was so supportive of what I wanted to do.”

So far, Brown has put on “Two Trains Running” and “King Hedley II” at the Matrix; she is hoping “Radio Golf” will be next.

When Arabian was offered the chance to direct the new play “The Double V,” his first thought was the Matrix. “This play is a major discovery,” he says. “It tells a story that should be taught in schools. And Joe really has built a reputation not just for great theater but for theater that brings a diverse audience, both racially and age-wise. And the location is great.”

The Matrix Theater keeps a deceptively low profile on the funky Fairfax-to-La Brea stretch of Melrose. Despite incursions by Urban Outfitters, Starbucks and a very fancy CVS, these dozen blocks are still mostly lined with vintage clothing shops, bars, gold grillworks and establishments with unprintable names to keep it real. The Melrose Art Wall is a block or so from the theater and passersby are encouraged to “Screw your fears, chase your dream” from a nearby wall.

That’s as good a slogan as any for the Matrix, and for Stern, who has been chasing his dream on Melrose for more than 40 years now.

Best known as TV producer for his work on high-profile shows including “Cagney and Lacey,” “Judging Amy” and “Law and Order,” Stern’s first love was theater, and for years his dream was simply to keep small theater alive in a town far more interested in film and television.

Stern grew up a few blocks away from the Matrix, though he took the long way home, working as an actor in New York where he got a job for $35 a week with Joe Papp and produced his first play at the Mercury Theater in 1969. He came back to L.A. in the ’70s, hoping for a film career, and bought the Matrix in 1977 with a friend, actor William Devane, to save it from destruction.

“It had been a psychiatric institution and Spike Jones’ soundstage,” Stern says. “I had told the guy who owned it that if he ever got into trouble, he should call me.”

When the owner did just that, Stern borrowed money from his father to pay his half, and again to buy out Devane in the early ’80s.

“When I first asked him, my father said, ‘Are you out of your mind?’ But here I am. Still.”

His first production was David Mamet’s “A Life in the Theatre” in 1980. Since then, he’s produced the West Coast premieres of such award-winning plays as Lyle Kessler’s “Orphans,” Harold Pinter’s “Betrayal” and Wendy MacLeod’s “The Water Children,” while working steadily as a television producer.

He had to — all of the Matrix Theater Company’s productions are self-financed. When he is not staging play, he rents the space out to other productions.

Set designer John Iacovelli has designed sets for the Matrix Theater for a decade; when he came on board for “Stick Fly,” he was struck by Stern’s deep commitment. “People tend to ghettoize black and Latinx characters [when they think of sets], and when you do a 99-seat play, they try to scrimp by. But Joe knows things cost what they cost.”

And things cost a lot in theater, especially with the new restrictions on 99-Seat Plan theaters. Although many plays are mounted in the Matrix, Stern’s Matrix Theater Company has never put up more than two plays a year; recently it has averaged just one.

Now, Stern thinks it might be another three years before he can personally produce another play, in part he believes because Actors’ Equity‘s decision two years ago to end the practice of allowing 99-seat theaters to pay performers nominal fees. “Scraps” was done with a non-Equity cast and, though Stern has long been known for aiding young performers, the task is easier, and audiences more eager, if there are one or two veterans in the mix.

“It will never be my last play,” he says. “I love the process too much. I love storytelling too much. But what am I doing next?” he adds with a laugh. “I want to get a job in television. I’m 79 and I’m looking for work. I’m hoping some of the people I’ve hired will hire me.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.