Was Lygia Pape making Frank Stella’s black paintings before Frank Stella? Does it matter?

As I face the weekend, I’m thinking about the braised pork at Luyixian in Alhambra. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, with the week’s essential arts news — and delicious pork products:

Who’s on first

There is no popcorn spectacle quite like watching artists and art historians squabble over who created something first. Was Russian-born painter Kandinsky the first abstract artist? Or does that honor go to Swedish painter Hilma af Klint? In the 1930s, Kandinsky wrote a letter to his New York art dealer noting that his first abstract work dated to 1911, therefore assuring him the status of first. In 2019, however, a show of Hilma af Klint’s work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York posited that Klint likely beat Kandinsky by five years. The idea that non-European cultures may have been engaging pattern and color in abstract ways — and, like Klint, with spiritual overtones — doesn’t generally enter the discussion.

I thought a lot about the race to be first after stumbling into a terrific exhibition of Brazilian artist Lygia Pape‘s prints at the Art Institute of Chicago in February. “Lygia Pape: Tecelares” gathers nearly 100 woodblock prints from the 1950s and ‘60s that show the artist experimenting with forms and shapes. Also at play was the organic nature of her materials. Printed on Japanese paper — some on silky and ethereal Gampi paper — she created the prints in ways “that would reflect the wood grain in the best possible ways,” says Mark Pascale, the Art Institute’s curator of prints and drawings. “She used a lot of hand printing so that she could use a press to elaborate how unique these surfaces were. She had tremendous control.”

Pape (pronounced PAH-peh) would later dub these works “Tecelares,” a play on the Portuguese word for “weave,” or “tecer.” The exhibition at the Art Institute marks the first time that this many Tecelares have been displayed in the United States. They are important precursors to some of her later, better-known works, including her ethereal Ttéias, luminous geometric installations of gold- and silver-colored thread that are tied from floor to ceiling or wall to wall and articulate aspects of light and space. (They caused a stir when displayed at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009, five years after her death.)

“The Tecelares are about space,” explains Pascale. “The negative space is activated by how she manipulates line and direction.” In the inkier pieces, Pape once said, she was “digging away at black” and “opening slices of light.”

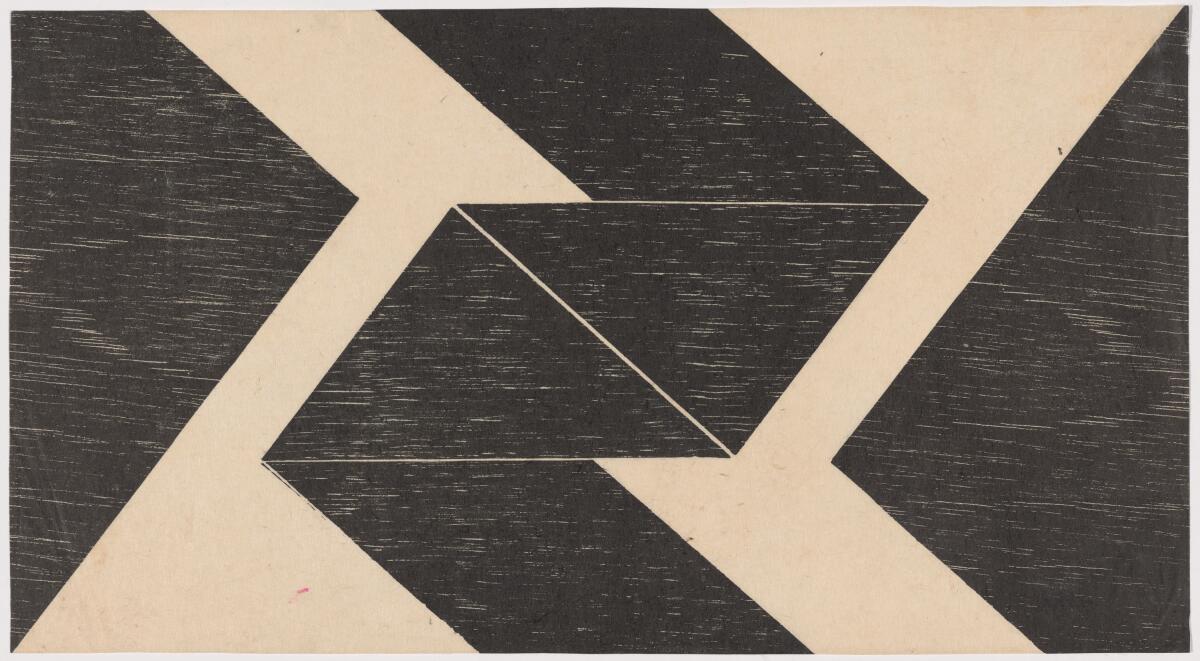

Which brings me to a particularly intriguing example of the ways in which the artist achieved this: a 1956 Tecelar that shows a concentric arrangement of white lines in an upside-down U set against a black background.

It may look familiar because it is the same hue and pattern as Frank Stella‘s well-known 1959 painting “Getty Tomb,” which is in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Both artists created a series of works that featured these types of geometric patterns rendered in black. Pape, however, came first.

Stella, by all accounts, began work on his famous Black Paintings in 1958, after seeing one of Jasper Johns’ flag paintings on display at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery. The Black Paintings were composed out of black enamel through which bands of exposed canvas create a sequence of repeating lines. In the 1960s, Stella produced a series of prints inspired by these works at L.A.’s Gemini G.E.L.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Pascale says it is highly unlikely that Stella ever laid eyes on Pape’s work when he was creating his pieces, since at that point, she would have been little known outside Brazil. In fact, Stella’s paintings are often described as a reaction/evolution to the emotive splatters of abstract expressionism. (See the catalog for the retrospective of his work held at New York’s Whitney Museum in 2015-16.)

But Pascale notes that both Pape and Stella were artists reckoning with the legacies of European modernism — from Mondrian to Malevich to Josef Albers — ideas that had achieved great prominence in the Americas as artists fled Europe in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Does it matter that Pape did it first? Well, it does take the gas out of some of the overheated prose used to describe purportedly prophetic male artists. (See this Christie’s listing for Stella, noting that his Black Paintings helped “usher” in “a brave, new world.”)

But, ultimately, it’s pretty irrelevant — since each artist arrived at this place for their own reasons. (In keeping with this idea, I’m hardly the first to notice the similarities: Blake Gopnik wrote about Pape’s Tecelares and their resemblance to Stella in 2017.)

What’s fascinating about the work of both artists is that they reveal the ways in which ideas exist not in isolation but as part of ecologies — deployed to different ends and effects.

I’m captivated by the ways in which both of their works feel handmade: Stella didn’t use masking tape on his paintings, and his lines often quiver; Pape’s prints bear the organic nature of her materials — the grain of wood and the grain of paper. But this work would lead to different ends: After the Black Paintings, Stella explored shape not just within the canvas, but also beyond it — creating shaped paintings and, later, three-dimensional works. Pape took her ideas about space into the arenas of installation and performance (including a ballet that involves moving shapes).

They are overlapping ideas explored as part of singular journeys. In our conversation, Pascale reminds me of a well-known quote by Robert Rauschenberg: “Ideas are not real estate.”

“Lygia Pape: Tecelares,” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through June 5; artic.edu.

In the galleries

For five decades, Bernard and Shirley Kinsey have collected art and artifacts connected with Black life in the U.S. — say, a rare edition of a book by Frederick Douglass, as well as works by important 20th century artists such as Faith Ringgold and Elizabeth Catlett. Many of these objects are now on view at SoFi Stadium, and contributor Leigh-Ann Jackson got to tour the show with the couple and their son Khalil Kinsey, who manages the collection. The collection, says scholar Tiffany E. Barber, offers “a complex visual picture of African American life across time and space.”

Over at LACMA, Times art critic Christopher Knight has a gander at “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing,” which looks at how Japanese art influenced his work — juxtaposing pieces by Francis with work by Japanese artists from the museum’s collection. But the show has only four significant paintings by Francis, relying primarily on prints. Does it work? Knight isn’t sold, but notes that this was a show that was shelved by the pandemic, then resuscitated.

MOCA Geffen‘s warehouse architecture can be a difficult place to see art — but maybe not when that art is inspired by the techno music that is often played at warehouse clubs. The exhibition “Carl Craig: Party/After-Party” features light and sound installations by DJ Carl Craig, whose roots lie in the Detroit techno scene. “Composed by Craig,” writes contributor Lina Abascal, “the audio ranges from thudding techno beats to white noise to frequencies audible only to listeners of certain age groups.”

How do you write about an artist that refuses to be written about? I really appreciate this piece about the elusive Stanley Brouwn by Jori Finkel in the Art Newspaper.

On and off the stage

The big news in L.A. theater is that Snehal Desai has just been named artistic director of the Center Theatre Group, taking over a role that was vacated by Michael Ritchie in 2021. Desai, who has served as artistic director of East West Players since 2016, becomes the first artistic director of color in CTG’s history. He takes the reins at a challenging time, report Jessica Gelt and Charles McNulty. “Buffeted by a series of crises and challenges beginning with the Great Recession and culminating with the COVID-19 pandemic and the social justice movement that arose in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the group is struggling to find its footing in a drastically changed artistic and sociopolitical landscape.”

McNulty sat down for a Q&A with the incoming director. “What I would love to do is to go outside of our theater walls and produce more site-specifically throughout the city,” says Desai. “I truly believe to change the flow, to get people to come to the theater, we have to first go meet them where they are and produce work that lifts up what it is to be an Angeleno.”

Dustin H. Chinn’s “Colonialism Is Terrible, But Phở Is Delicious,” presented by Anaheim’s Chance Theater uses comedy, three narratives over three periods and one of Vietnam’s most delicious dishes to examine questions of colonialism and the quest for control. “Chinn’s comedy of ideas demands more subtlety,” writes McNulty in his review of the show. “But the larger point about the way a dish can preserve the relentless discord of history is delectably served.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

I really enjoyed this profile of the Pulitzer Prize- and Tony-winning Michael R. Jackson, the writer behind the musicals “A Strange Loop” and “White Girl in Danger,” by Hilton Als.

On the screen

The new feature film “Showing Up” follows the lives of a Portland sculptor named Lizzy (played by Michelle Williams) who struggles to make work as she contends with life’s mishaps: a broken water heater, a dreary day job, parents and friends who provide little support. The Times’ Steven Vargas writes about the artists — Cynthia Lahti, Michelle Segre and Jessica Jackson Hutchins — who supplied art and technique and helped bring Lizzy’s milieu to vivid life.

ICYMI: Critic Justin Chang’s review of the film.

Literary L.A.

I’m putting on my reading glasses (as soon as I find them) and diving into the Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf, a compilation of the 110 essential Los Angeles books. It’s got fiction, nonfiction, essay, poetry, memoir, speculative fiction and much, much more — and was lovingly assembled by books editor (and my editor) Boris Kachka. I made some contributions to the package here and there, contributing write-ups on Octavio Paz, Maggie Nelson, Natalia Molina and Sesshu Foster.

If that is somehow not enough, the special package, which debuts in advance of next week’s Festival of Books, also includes essays by writers on writers and a list of the best L.A. books of all time. So get ready for the literary fisticuffs.

Moves

Trump disbanded the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, but Biden has now restored it. Lady Gaga and producer Bruce Cohen will serve as co-chairs. Among the various new committee members are actor Anna Deavere Smith, curator Nora Halpern and artist and educator Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya.

Ariana DeBose has been tapped to host the Tony Awards for a second year in a row.

Bank of America announced its 2023 Global Art Conservation Project recipients this week — on LACMA’s campus — and one of the 23 international recipients, which also includes projects in Hawaii, Phoenix and Florida, was Chris Burden’s 2008 “Urban Light.” Find the full list of grantees at this link.

Passages

Mary Quant, a ‘60s-era fashion designer known for her leg-revealing miniskirt and her influence on London’s youth culture, has died at 93.

Kwame Brathwaite, a New York photographer who chronicled the joy and beauty in Black culture, has died at 85. My former colleague Makeda Easter wrote a great piece about Brathwaite’s work when the exhibition “Black is Beautiful” landed at the Skirball in 2019.

Al Jaffee, a Mad Magazine cartoonist known for his humorous “Fold-In,” is dead at 102.

In the news

— Habibe Jafarian has a very worthwhile essay in Guernica on what it means to be a woman and a journalist in Tehran.

— I am here for Greg Allen‘s obsessiveness chronicling the fake lever that the late right-wing billionaire David Koch used to turn on the real fountains in front of the Metropolitan Museum.

— I’m also always here for Gary Indiana talking about anything, such as his fiction: “They were never written to be sold in airports.”

— L.A. auctioneer Michael Barzman admitted to lying to the FBI about Basquiat forgeries that appeared at the Orlando Museum of Art in 2022.

— An episode of “Hawkeye” on Disney+ featured a cringe faux musical inspired by the story of Marvel’s Captain America. At the prodding of fans, a real-deal musical is about to land in Anaheim.

— A performance of “The Bodyguard” musical in England was disrupted by rowdy viewers attempting to sing “I Will Always Love You” along with the cast.

And last but not least ...

While I proudly remain a terrible Catholic, this year, I’ve been enthralled by Holy Week Tok, watching just about every video of just about every over-the-top procession from Patagonia to Málaga, and all I gotta say is: Ayacucho wins.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.