How the pandemic made us less human (hint: automation)

- Share via

It’s officially Beyoncé “Renaissance” weekend. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here for throwback house jams. (Oh, those days of dancing to Frankie Knuckles until 5 a.m. at the Sound Factory Bar in Manhattan!) As always, I’m also here for some essential arts news:

I, robot

My colleague Mary McNamara recently wrote a funny and insightful column about how dreaded DIY checkouts in retail outlets seem to be materializing in ever greater numbers — and the crushing soullessness these interactions represent. “You are now also expected to pull unpaid clerk duty,” she writes, “while being treated to regular demands that you put your item in or take your item out of the bagging area made in the chilling monotone of a Dalek announcing its intention to ‘exterminate.’”

And it’s not just supermarkets and drugstores. As she notes, Dodger Stadium recently installed self-serving beer machines.

Automation is not new. For decades, we have gotten our cash from automated tellers, navigated automated phone trees in search of a customer service rep (nightmarish), checked in for our flights through digital kiosks at major airports and had our houses cleaned by robot vacuums. (A favorite subcategory of TikTok vid is a cat on a Roomba — hours of which you’ll find under the hashtag #roombacat.)

There is also the phenomena known as autonomous cars, which have basically turned our public streets into a site of rather terrifying experiments in automation. And if you think that’s freaky, the other day I was listening to the Guardian’s “Today in Focus” podcast and they were interviewing Abdurzak Hadi, an Uber driver in London who organized fellow drivers to improve labor conditions. He describes not just having his routes and fares determined by the machines, but also messaging the company with legitimate questions about work issues and likely having those responses generated by a bot.

We don’t just employ robots, we are working for them.

COVID-19 made what had felt like automation creep manifest into a full-blown phenomenon.

Early on in the pandemic, the Colombian home delivery service Rappi teamed up with Kiwibot, a Colombian-owned tech company, to deploy cute little street bots to deliver food and medicine around Medellín during the lockdowns. (I saw a similar delivery bot traveling down Melrose Avenue last November and shot this video of it.)

In hospitals and airports in countries such as the U.S. and China, disinfectant robots have been employed to keep spaces sterile. These could be adapted with sensors to scan people’s temperature or be programmed with object-recognition algorithms to see if humans are wearing their masks.

Less cinematic but more significant were the myriad takeout and delivery apps that flourished during the pandemic. I no longer had to talk to a human either on the phone or in person to get my Japanese fried chicken. I could simply tap a few icons on my smartphone, then show up at the assigned time and pluck a bag with my name off a shelf.

Naturally, all of that automated convenience comes at a price — one that was paid by small business owners, who were having the lifeblood drained out of them by app companies charging exorbitant fees.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As we enter Pandemic 3.0 — 3.5? 4.0? I’ve lost track of the releases — many of these sorts of digital interfaces and automated systems are liable to stick around for the long haul. This could be bad news for workers. Though, to be certain, the long-term effects are still unclear.

But it will definitely be bad for humans.

In 2017, I wrote a lengthy story for the Atlantic about how automation was reshaping architecture. It’s also reshaping the way we interact with other people — if we are interacting with them at all.

I don’t go to my local mercadito simply because I need a Diet Coke. I go to clear my head between deadlines and hear about the mischief the owner’s dog has been up to. Those simple transactions create a kind of human glue. Automation strips them away. And the pandemic, with its social distancing requirements, has certainly accelerated that.

“It’s seemingly trivial encounters that are important to society and their health,” curator Rory Hyde, who was then with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, told me back in 2017. “We have to remember the value of those little encounters as we automate them all.”

That beer at Dodger Stadium? Maybe it can wait five minutes for a bartender — and an experience that will make us more human in the end.

On and off the stage

The racial reckoning of 2020, which brought calls for social justice and racial equality across just about every sector of society — cultural, academic, political and commercial — also played out in the world of theater. In the wake of that, many organizations hired artists of color and presented works centered on those experiences, reports The Times’ Jessica Gelt. “Over time, however, critics have raised concerns that this commitment was proving to be more performative than profound.” In a deeply reported piece, Gelt takes a look at the case of Long Beach Opera and the chain of events that led to the departure of three Black members from the company — including the associate artistic director as well as the director of the 2022 season’s opening show. In a statement to The Times, LBO said an internal investigation had found no evidence of bias.

Visual arts

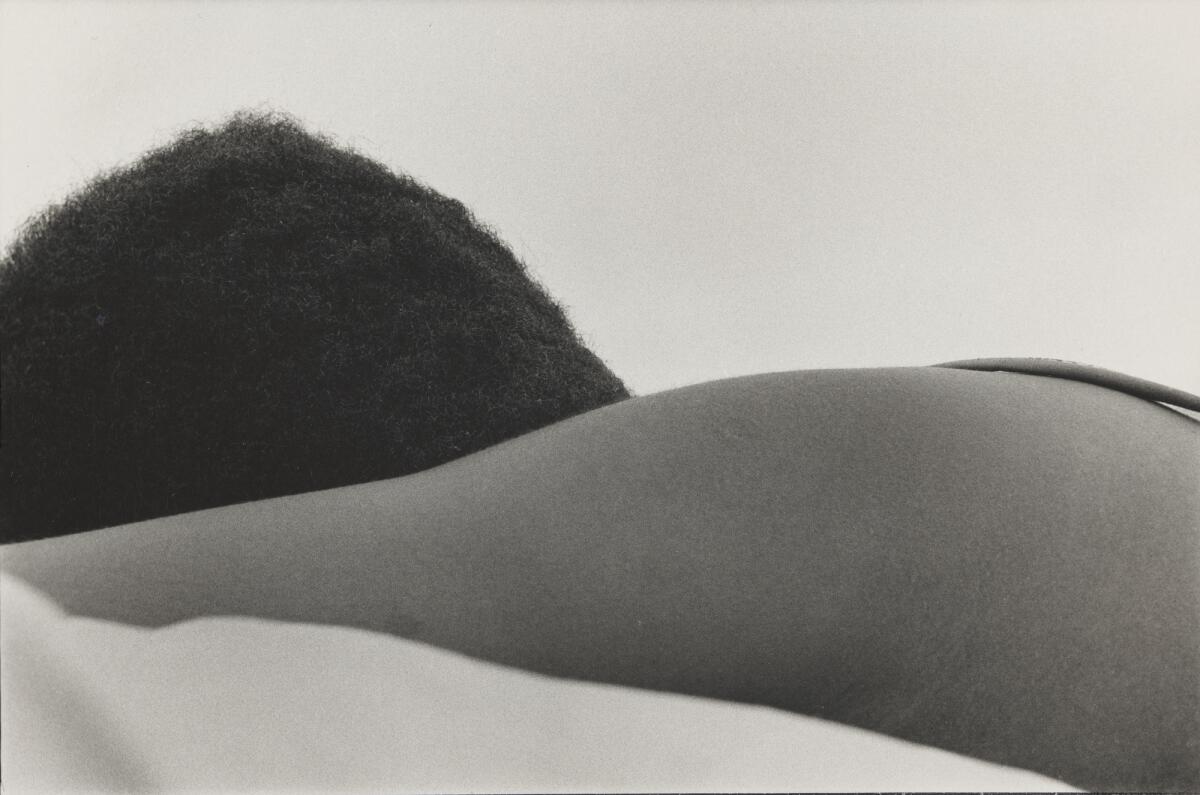

At the Getty Museum, the exhibition “Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop” is an “engrossing” exhibition that charts the impact of artist Louis Draper, reports art critic Christopher Knight. Draper founded Kamoinge, a loosely affiliated group of more than a dozen Black photographers in the early 1960s. “In mass media, white perceptions of Black life dominate,” writes Knight. “Those observations weren’t always wrong, but they were inevitably limited, repetitive and exclusionary. The Kamoinge Workshop put disparate representation in the foreground.”

The Petersen Automotive Museum has gathered several dozen silk-screen paintings and pencil drawings by Andy Warhol from 1987, when he was commissioned by Mercedes-Benz to paint some of their more notable automobiles. Warhol never completed the project — he died unexpectedly before it was done. “As with much of what Warhol painted in the late 1970s and 1980s, after the nearly faultless run of superlative, art-history-changing works he produced between about 1961 and 1968, the Mercedes paintings are banal,” writes Knight in his review. “The vehicles, on the other hand, range from fascinating to extraordinary.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

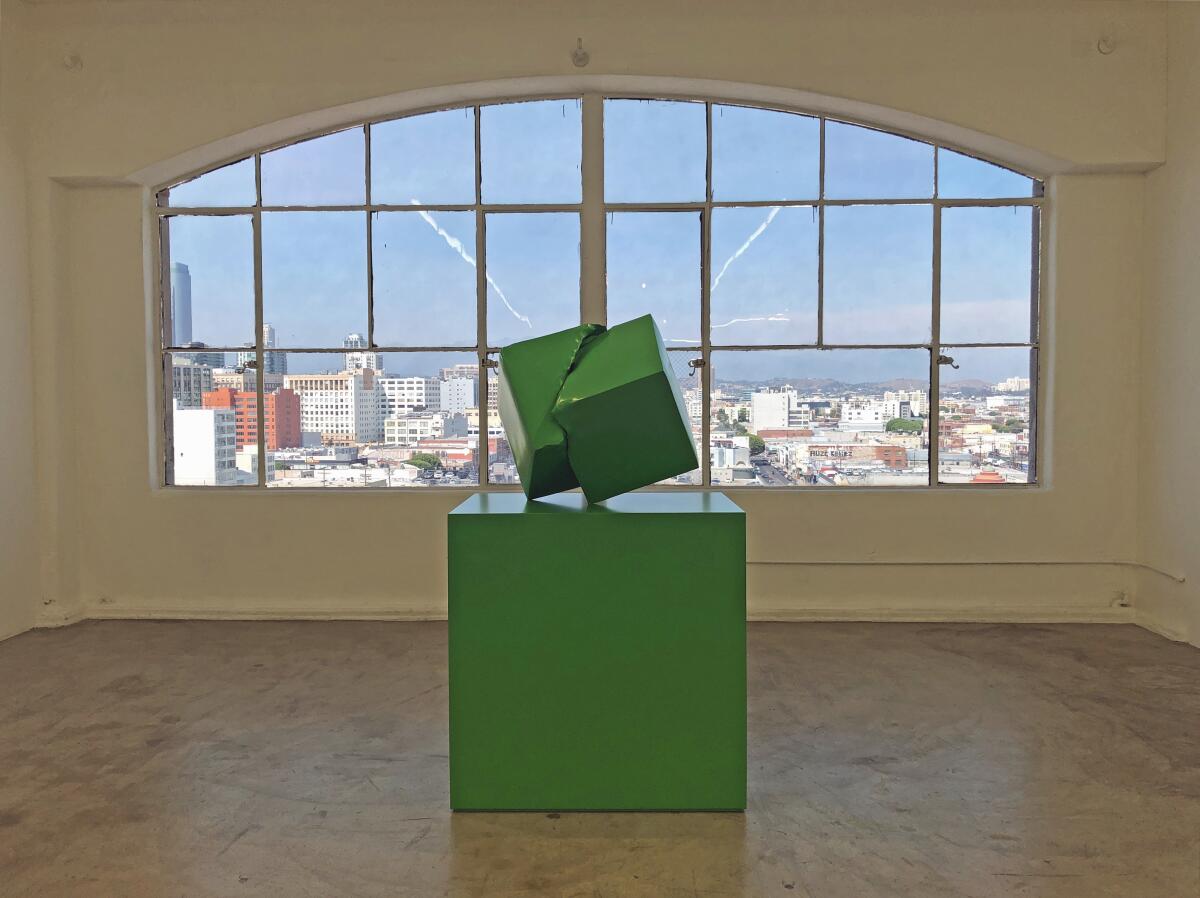

My colleague Deborah Vankin, in the meantime, examines why East Coast galleries are all up in L.A.’s grill — and why some L.A. spaces are expanding into multiple locations. “Part of what’s driving the recent influx of New York galleries is circumstance — including healthy pandemic-era sales among many established galleries that are now poised for expansion, as well as L.A.’s current museum boom and its growing art collector community,” writes Vankin. “But it’s also a cyclical phenomenon, says Peter Goulds, founding director of the long-standing gallery L.A. Louver, which has operated in Venice for 47 years.”

As he puts it: “This isn’t the first time this has happened. There’s a lineage of this evolution — galleries coming from New York and even Europe — we’re just at the next crossroads.”

Looking forward to the continuing stories about how culture has finally — finally — landed in L.A.

Design time

During my spring trip to Denver, I got to spend quality time at Italian architect Gio Ponti’s only North American building: the seven-story gallery tower he helped design for the Denver Art Museum. It’s a strange building and not entirely Ponti’s. Rather, it was a design-by-committee project that included galleries devised by former director Otto Bach, public areas by Denver architect James Sudler, with a facade by Ponti. Oh, and it resembles a medieval castle — the sort that might appear in “Game of Thrones.” Ponti’s building recently got a smart revamp and expansion by the Boston-based Machado Silvetti and it is looking spiffy. I dig in to a structure that channels the “eccentric uncle” vibe.

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper has got the end of July covered, with the eight best bets for the weekend, including a performance of “Carmina Burana” by the L.A. Phil and the L.A. Master Chorale at the Hollywood Bowl and Gallery Weekend Los Angeles 2022 — with spaces around town staying open late on predetermined evenings.

Moves

Two L.A. artists — Alison O’Daniel and Nasreen Alkhateeb — have been awarded grants of $50,000 each by the Disability Futures Fellows, a multidisciplinary initiative led by the Ford Foundation and the Mellon Foundation.

At SFMOMA, Erin O’Toole has been named curator and head of photography (after serving in an interim capacity) and Katy Siegel, previously of the Baltimore Museum of Art, has joined as research director of special program initiatives.

The Getty Trust has committed $30 million to digitizing the Johnson Publishing photographic archive, which includes almost a million images produced for Ebony and Jet magazines.

Passages

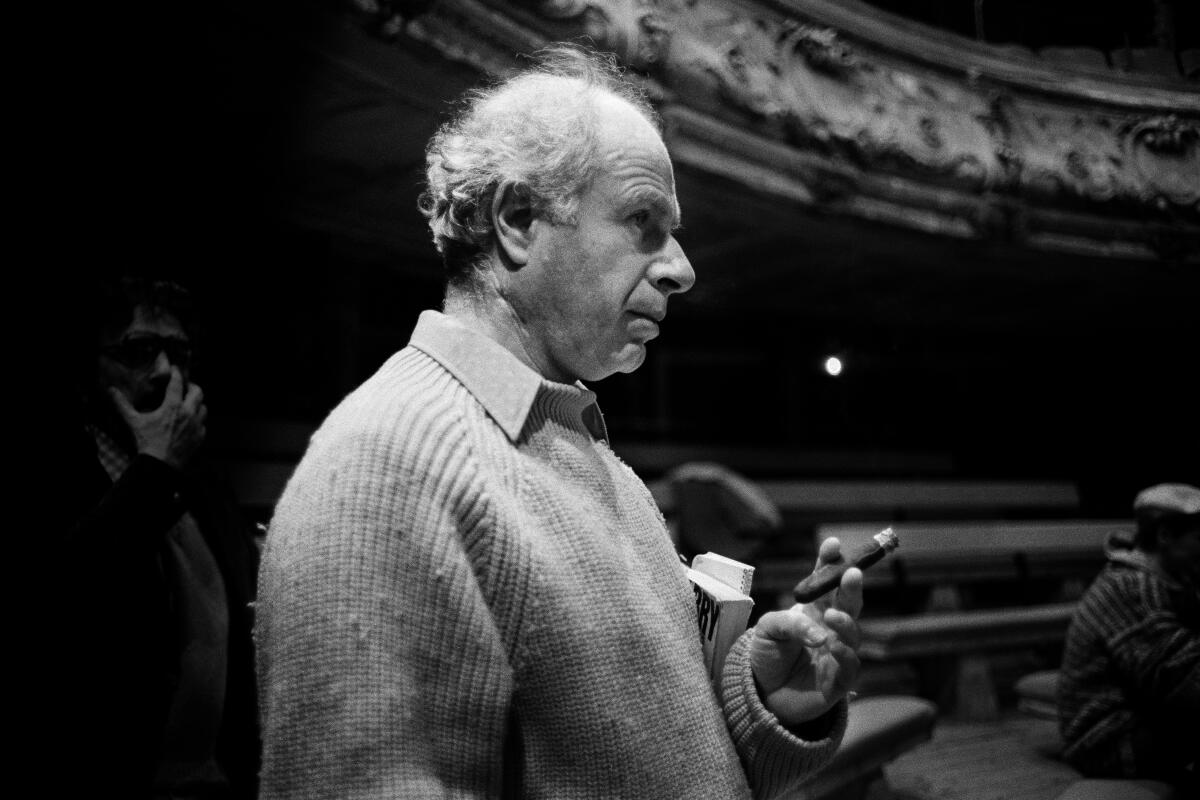

Times classical music critic Mark Swed pens an appreciation to director Peter Brook and musicologist Richard Taruskin. He notes that the two couldn’t have been more different — in demeanor and in profile. But “one thing that profoundly joins them is that, while neither was quite what he seemed on the surface, each was possessed by the need to dig under surfaces,” he writes. “Each was an exposer extraordinaire: in Taruskin’s case, a composer like Stravinsky; in Brook’s case, an opera character like Don Giovanni.”

Jennifer Bartlett, a Long Beach-born painter who, in her work, rejected the divide between abstraction and figuration, has died at 81.

In other news

— “Why listen to music, why look at art, why go to the theater when war is raging?” New York Times art critic Jason Farago reflects on the role of culture during a trip to Ukraine.

— If you read one thing this week, make it Joshua Hunt’s staggeringly beautiful profile of artist Cannupa Hanska Luger.

— Chun Wai Chan is the New York City Ballet’s first principal dancer of Chinese descent.

— A photo shoot by Annie Leibovitz of Ukrainian First Lady Olena Zelenska for Vogue has ignited fierce debate.

— Barack Obama has released his annual reading list.

— The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos has a rather incredible report on the rise of the superyacht, featuring some amazing design details (cryosauna anyone?). It’s a story that will lead you to only one conclusion: Tax the rich.

— A sculpture of a gorilla, bananas, wild crypto speculation and a cross-country drive. This is a wild story.

And last but not least ...

Speaking of robots ... I’ve been hanging out on Midjourney, an artificial intelligence bot that renders images. Feed it a description and it will generate an image (or what it thinks that image might be). Naturally, I’ve been playing with it way too much.

Here’s how Midjourney imagined a taco truck designed by Frank Gehry — 10/10 would eat.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.