Newsletter: QR codes in museums can be a blessing. They are also a curse

- Share via

Thank God the internet is here to explain the internet, because otherwise where would I be on the dating life of West Elm Caleb, a Manhattan Lothario known for ghosting the ladies. Or at least that’s what TikTok says. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and sometimes it’s hard to keep up with the kids. Thankfully, I am keeping up on the culture:

Give the QR codes a rest

In the early 1990s, Masahiko Hara, an engineer at Denso Wave Inc., a global auto parts manufacturer that falls under the Toyota umbrella, came up with a new type of bar code that could hold exponentially more information than the vertical bar patterns in use at the time. The QR code, as Hara’s code is now better known, emerged out of a very specific need: to better manage inventory at Denso factories. Since the average bar code can only hold 20 or so alphanumeric characters, the factory was using multiple bar codes to track parts through a complex system of inventory and shipment — requiring multiple scans at every stop in the supply chain. By contrast, a single QR code could contain hundreds of characters’ worth of information and therefore only require a single scan.

The QR code — a square that contains a pattern of black and white squares of varying dimensions within — has since become ubiquitous, especially since the early 2000s, when cellphones with QR readers were made available to the public.

QR codes have since appeared on advertising billboards, allowing customers to make on-the-spot purchases or bookmark them for later. In 2009, Japanese architectural studio Terada Hirate Sekkei covered the facade of an entire Tokyo building in a QR pattern. Three years later, the city of Rio de Janeiro embedded QR codes into popular tourist locales around the city so that visitors could scan them to learn more about a site. Last year, a painting by Mario Ayala at the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial titled “Angel’s Fruits” bore a QR code that, when followed, took you to a musical playlist on YouTube.

The pandemic has made QR codes even more ubiquitous: employed as event tickets, to view restaurant menus, in digital health passes and vaccination cards as well as, increasingly, in museums.

They are a blessing and a curse — and a lesson that more technology doesn’t always make life easier.

In the best scenarios, QR codes have served as an additive. At the Hammer Museum, they have recently materialized at the entrance of exhibitions such as “Witch Hunt” and “No Humans Involved” and can be scanned for information that goes beyond the exhibition’s wall text. This includes curator commentary, additional texts and video that is viewable through the Bloomberg Connects app, a digital platform created by Bloomberg Philanthropies to support cultural institutions.

At L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, QR codes have likewise been used largely as additive. During live performances, they have been deployed as a way of leading viewers to a PDF program of the show. For visual arts installations, QR codes are used to connect visitors with a digital Spanish-language guide. (I’ll save my rant, about how L.A. museums should have English and Spanish wall text at all times, for another day.)

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has likewise been using them in this way, though, as of late, the museum’s QR code use has gone from techno-additive to grating digital tic.

Earlier this week, I paid a visit to LACMA’s sensational “Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico,” where I was greeted by a gesture of accessibility: an opening wall text in four languages, including Nahuatl and Zapotec. After which I was left to puzzle out the series of works made by Indigenous scribes in Mexico in the early colonial era — because the show featured absolutely no wall text beyond the title, credit and material type. For any sort of information, I was required to scan a QR code.

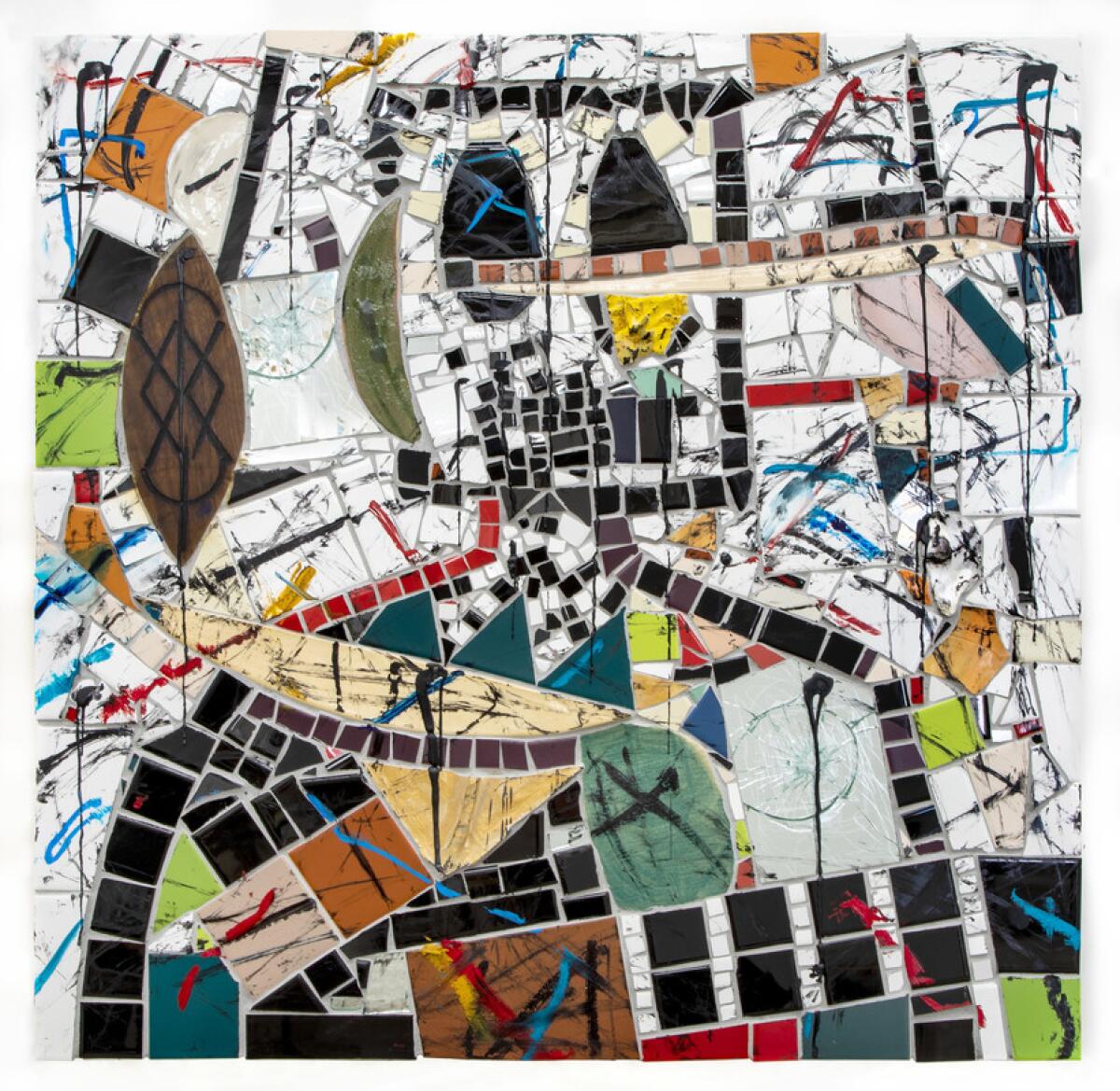

Included in the show, for example, is an absolutely exquisite drawing that shows a mysterious series of bundles, as well as a rendering of a bird and various human heads. The piece is titled “Idols From the Temple of Huitzilopochtli” and was originally created in 1539. (The museum has a contemporary re-creation on view.) To find out what I was looking at, I had to scan a QR code next to the work, which explained that the painting documents the ways in which the Mexica leaders of the early colonial era had hidden a cache of sacred objects from the invading Spanish as a way of preserving their cultural traditions.

Audio was also available, but it wouldn’t play on my phone because LACMA’s online guide didn’t work with my default browser. So I had to cut and paste the link into another browser so that I could hear what curators had to say about the work.

As the kids like to say: hard pass.

I am no Luddite when it comes to technology. There is a benefit to creating experiences that make the work on view accessible in ways that go beyond the museum or that help the museum reach different audiences. (QR codes, for example, can help visually impaired visitors more fully experience an exhibition.) But replacing basic wall text with QR codes strikes me as erecting a barrier around the most basic knowledge a visitor travels to a museum to absorb.

A LACMA spokesperson says the museum is “still experimenting heavily with QRs” and that some of the use was driven by the pandemic — to prevent people from gathering around wall texts at a time in which we still need to be social distancing. But I wonder how many people will enter and leave that gallery without going through the trouble of scanning the codes and therefore will depart LACMA without even the most basic understanding of what they have just seen. My mother-in-law still carries a flip phone — how is she supposed to find out what the bird drawing means? And what do I do if my phone battery is dead?

This is a case of technology subtracting from the experience. I spend enough time on my pocket doom machine. In the confines of a museum, it’d be nice not to be obligated to reach for it.

Visual arts

Since we’re on the subject of LACMA, art critic Christopher Knight reports about the museum’s unusual arrangement with Interscope Records — namely, an exhibition to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the record label. “Artists Inspired by Music: Interscope Reimagined” opens at LACMA on Jan. 30 and will feature work by 46 artists commissioned by the label to celebrate its artist roster, including Lady Gaga, Kendrick Lamar and Dr. Dre. Allowing such an exhibition, writes Knight, “usurps the role of museum curators.” It also raises the specter of pay to play, and that, he adds, “should be a matter of considerable concern — especially for the Board of Supervisors that oversees the county facility.”

The New York Times had an extensive investigative piece last year on the Artist Pension Trust, a business that had promised artists a retirement-fund-type plan based on the sales from a pool of their art. Well, that organization seems to have fallen apart — without artists being able to retrieve the work they had contributed.

Now, L.A. art writer Catherine Wagley follows up with another story — in two parts — that looks at how artists are struggling to get their work returned. She reports that 61 Los Angeles artists have signed retainer agreements with a lawyer to retrieve their work from the company. And she looks at how artists and galleries are looking for new ways of creating networks of mutual support.

Performance notes

Classical music critic Mark Swed writes that Michael Tilson Thomas’ L.A. Phil concerts have become a bit of a hot ticket, because attendance at his last show was “sizably larger” than previous gigs. The most recent show included a “staggering” performance of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony and a rendition of Alban Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra, which captured the disquiet that resides amid this “labyrinthine description of chaos.” “There was beauty galore in the thousands (yes, thousands) of tiny details, glittering sonic shards that peered through the huge orchestra, like brilliant cutouts on a vast canvas,” Swed writes. “Through it all, Tilson Thomas retained the big picture.”

Culture and coronavirus

As Omicron continues its march through our collective immune system, leading to the cancellation or rescheduling of countless events, including the Palm Springs International Film Festival and performances of “Hamilton” at the Pantages, art fair season is nonetheless moving forward. The L.A. Art Show kicked off this week, the first of five large-scale, in-person fairs taking place through February in the region, including Frieze andFelix Los Angeles, reports Deborah Vankin. “As public health guidelines continue to evolve and pandemic fatigue further sets in,” she writes, “the widely varying perspectives on personal and institutional safety add up to something of a ‘choose your own adventure’ approach.”

Vankin also profiles the L.A. Art Show’s youngest-ever exhibitor: 14-year-old Tex Hammond.

As Broadway is walloped by Omicron, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has proposed expanding a tax credit intended to help the commercial theater industry rebound.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The Times’ Jessica Gelt writes that even as Omicron has been described as a mild variant that is “really not that scary after all,” she says she’s not ready to shed the extreme caution. “I remember the traumatized family members I interviewed for a series of pandemic obituaries — the agony they expressed over their loved ones dying alone,” she writes. “I remember these things happened. And I know they could happen again. What Greek letter comes after Omicron?”

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper has THE rundown for the weekend’s eight best bets, including the musical “Everybody’s Talking About Jamie” at the Ahmanson and Jazz at Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in O.C.

A recent trip to New Orleans had me digging up Marsalis’ early record “Black Codes.” In his review of the album in 1985, Geoffrey Himes of the Washington Post got at Marsalis’ complicated legacy as a musician, an artist who “is refining a tradition rather than extending it” but with a playing technique that can’t be touched: “On the title track, Marsalis sketches out his theme with diamond-hard notes that never once weaken. Every phrase is concise.”

Last chance! It’s the final weekend to see Sanford Biggers’ “Codeswitch” at the California African American Museum. The exhibition features the artist’s sculptural paintings, made from deconstructed and reconstructed quilts. As Christopher Knight wrote in his review of the show last year, the works “radiate pleasure in the making — a smile that reverberates in manifold ways.”

Incidentally, one of Biggers’ quilt paintings, “Quilt 35 (Vex),” 2014, contains a QR code that takes the viewer to a website that links to, among other things, video by the artist.

Passages

Steve Schapiro, a photojournalist who chronicled the civil rights movements and captured visceral moments in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis, has died at 87.

André Leon Talley, the influential fashion journalist whose very name conjured Vogue magazine, where he served for many years as creative director, has died at the age of 73. Talley, who reached the top ranks of fashion at a time in which Black faces were rare in the industry, had a profound sense of fashion history. “He can see through everything you do to the original reference, predict what was on your inspiration board,” designer Tom Ford once told Vanity Fair.

Italian fashion designer Nino Cerruti, who revolutionized men’s ready-to-wear fashion in the ’60s and gave Giorgio Armani his first break, has died at 91.

In other news

— Jason Farago at the New York Times has a beautifully produced series called “Close Read,” in which he picks apart single works of art. I particularly enjoyed a recent post devoted to Jasper Johns’ “In Memory of My Feelings — Frank O’Hara,” from 1961. It’s incredible the stories you can tell with gray paint.

— Artist Tracey Emin says she has made an official request that her 2010 neon piece, “More Passion,” be removed from 10 Downing St. in response to Boris Johnson’s “partygate” scandal.

— Marfa, Texas: NFT town.

— A new database devised by a team led by scholars Karen Mary Davalos and Constance Cortez, allows users to search Mexican American art since 1848.

— Cynthia Chavez Lamar, a member of the San Felipe Pueblo, an Indigenous tribe based in New Mexico, has been named the new director of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

— An equestrian monument to Theodore Roosevelt, in which the former president is flanked by representations of an African man and Indigenous man on foot, is being removed from its spot in front of the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

— Rolling Stone reports on a brewing controversy at L.A.’s Academy Museum and whether the debut installation overlooked the critical role of Jewish immigrants in the story of film.

— Buildings could be designed to be bird safe, writes Alexandra Lange. Unfortunately, bird-safe design doesn’t always jibe with the big-window desires of the real estate class.

— “It wasn’t the flames that endangered us. It was the indifference.” A beautiful essay from David Gonzalez about the significance of fire in the Bronx.

— Also beguiling is Daphne Merkin on Joan Didion: “Didion’s work tragically, if unwittingly, anticipates our bewildered, agitated and insolubly divided culture, where the void she stared into so unflinchingly has become the climate in which we live.”

And last but not least ...

Hear! Hear! to TikTok user @thegoogleearthguy.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.