A Tupac Shakur pop-up museum becomes focus of lawsuit over who owns its contents

Tupac Shakur has risen multiple times since his death in 1996.

He appeared through his posthumous book “The Rose That Grew From Concrete,” which highlighted selections from his then-unreleased collection of poetry. His likeness was taken to the big screen in the 2017 biopic “All Eyez on Me,” the drama that attempted to document his illustrious life story. And perhaps most convincingly, he appeared at the Coachella main stage beside Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg in 2012, rapping “Hail Mary” and “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted” in holographic form beside the two West Coast legends.

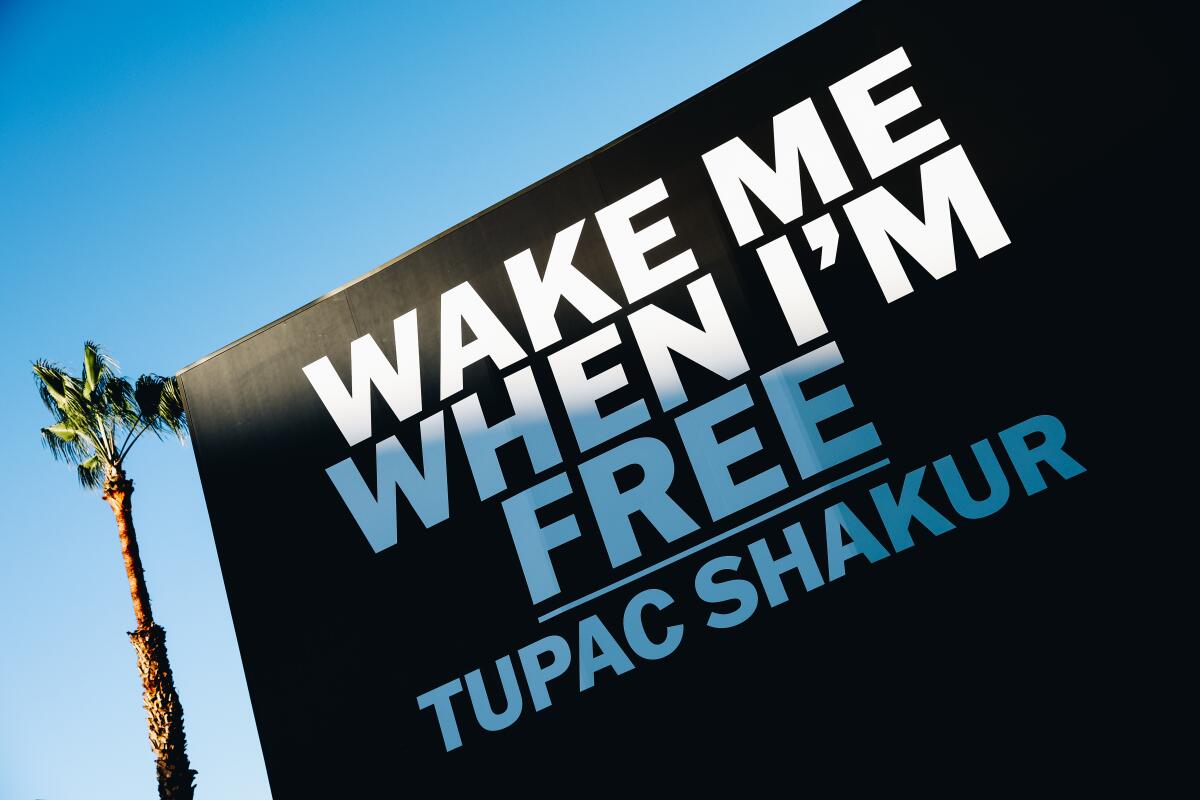

Now, he’s back to life once again through “Wake Me When I’m Free,” the traveling museum exhibit that chronicles the life and legacy of the revolutionary artist. Located at L.A. Live, the exhibit was created in tandem with the Shakur estate, with the initial idea coming from his mother, Afeni Shakur, before she died in 2016.

The exhibit, which will live in Los Angeles until May before moving to other cities, opens in a glossy white room, a stark contrast from the rectangular black box that forms the building’s exterior. Inside the lobby, larger-than-life renditions of Tupac’s various tattoos protrude from the walls, giving museum-goers a deeper understanding of the art that decorated his body.

Arron Saxe, the exhibit’s producer, wanted “Wake Me When I’m Free” to be “more than a hip-hop museum.” For that reason, the first few rooms are dedicated to Afeni Shakur, and the revolutionary philosophies she imparted on him that would inform his work.

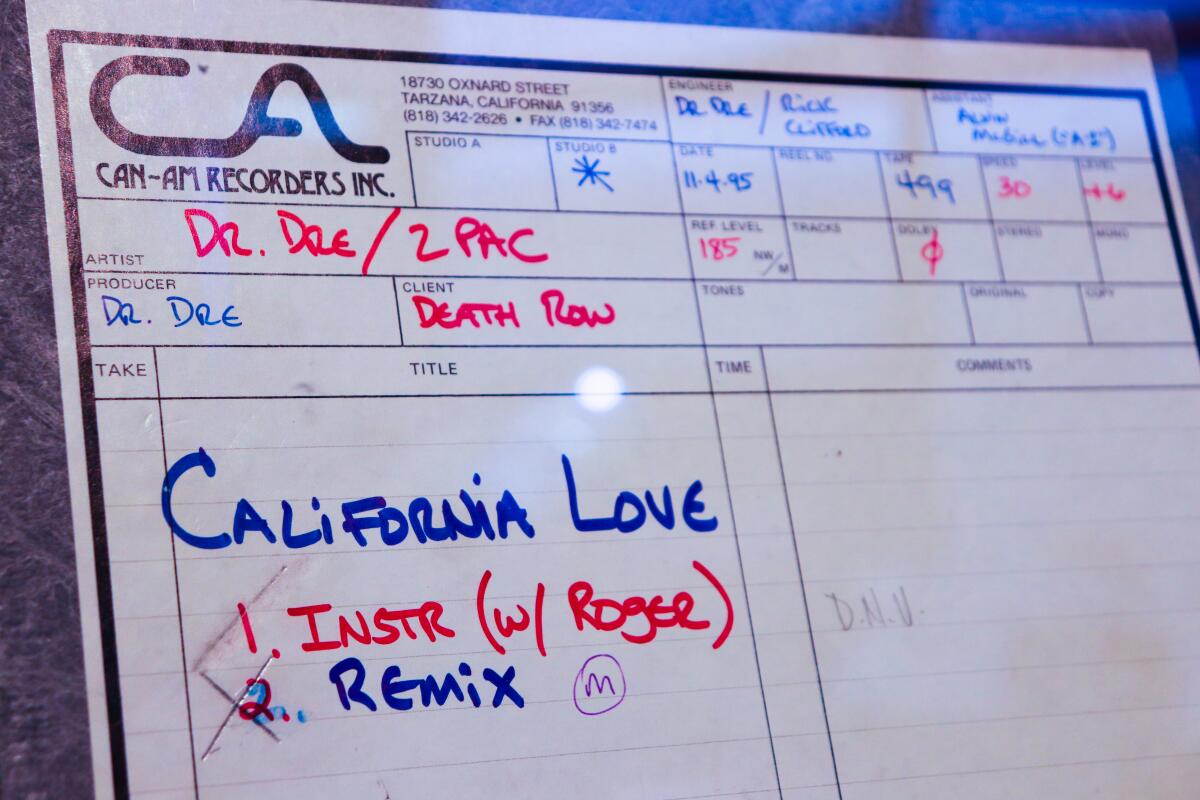

After zoning in on his upbringing, the walkway opens up to an array of school-lined paper, scribbled over by the prolific creative with handwritten poems, song lyrics and iterations of album track lists excruciatingly revised until reaching their final form.

“I would hope people are down here on the floor, looking at these screenplays,” said head curator Nwaka Onwusa, crouching down to get a closer look at pages from Tupac’s screenplay “Live 2 Tell.”

“Wake Me When I’m Free” is the latest effort to pay tribute to the life of an artist taken before his or her time. In the past decade, there have been documentaries on Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse and Kurt Cobain, along with retrospectives on younger artists who recently passed away such as Juice WRLD, Lil Peep and Mac Miller.

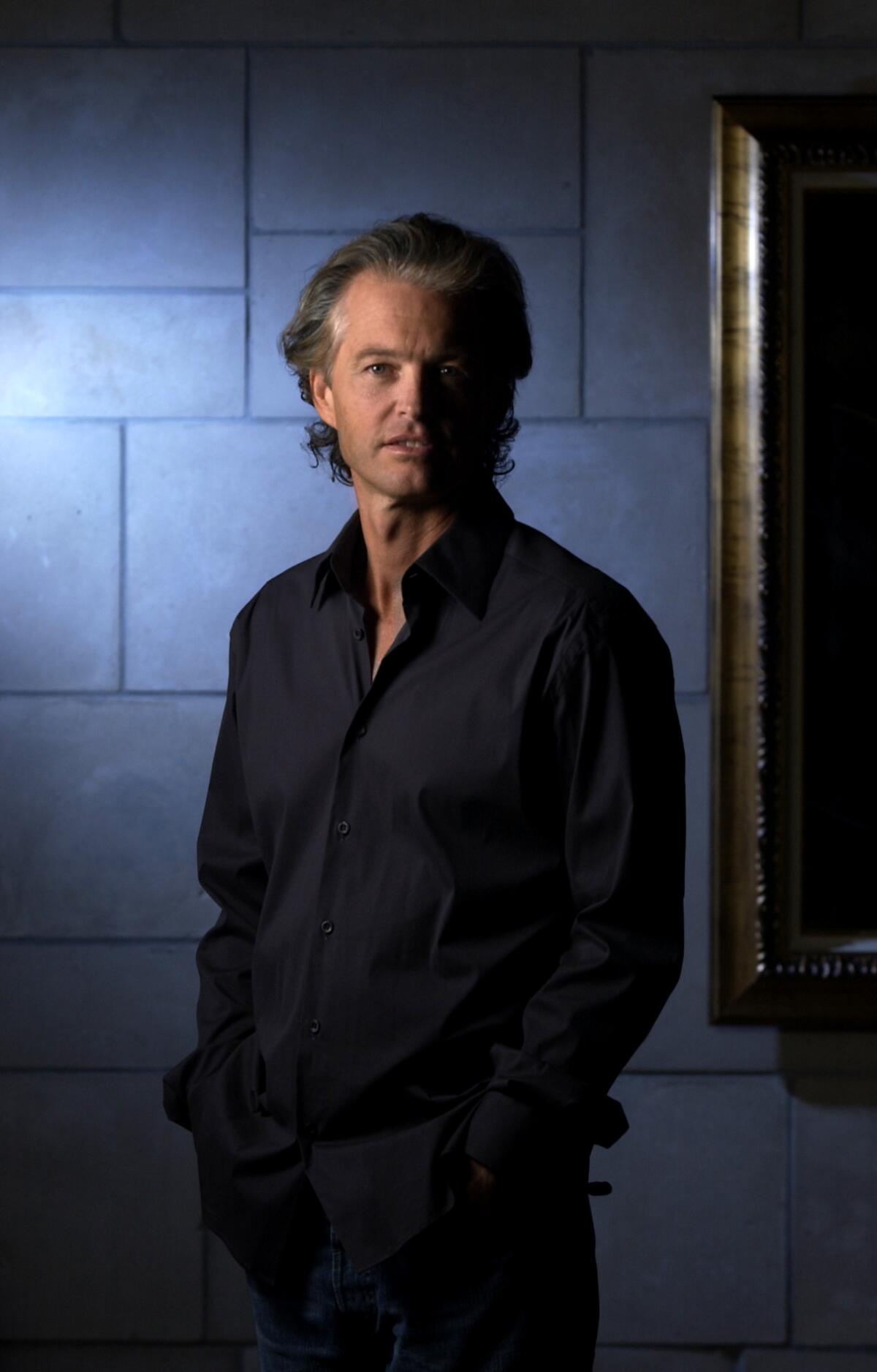

“You’re taking the idea and the legacy of this artist, and if you can connect that magic to an 11-30 year old, they can become instantly interested in everything that artist did,” said Jampol Artist Management CEO Jeff Jampol, who previously managed Shakur’s estate and currently manages the estates of artists such as the Doors and Janis Joplin.

Old music — anything released outside of the past 18 months — now makes up 70% of the U.S. music market, according to music-analytics firm MRC Data. The increased attention to such songs have made the business of legacy artists, including those who are no longer living, increasingly profitable.

David Bowie’s estate recently sold his global publishing rights to Warner Chappell Music for over $250 million. Not long before, Bob Dylan sold his songwriting catalogue to Universal Music Publishing Group for at least $300 million. (An estimate of the value of Tupac’s estate wasn’t available.)

While it’s difficult to assign a singular reason for this growth, streaming services have made it easier for younger fans to latch onto music from icons from yesteryears and for older fans to relive their childhood soundtracks. The potential of hologram tours and NFTs, along with tried and true methods such as documentaries and posthumous albums, have also created more avenues to expand an artist’s legacy outside of their recorded music.

At the same time, the newfound abundance of art competing for our eyes and ears makes it harder for aspiring musicians to reach the same pinnacle their predecessors once did.

“There was a time in the ‘60s and ‘70s when there were less than 300 albums commercially released each year,” Jampol said. “Today, there’s 60,000 tracks uploaded to Spotify each day. It’s made it easier for unknown artists to develop a handshake relationship with eventual fans, but it’s made it almost impossible to break through the clutter.”

“Wake Me When I’m Free” isn’t the only way Tupac’s name has returned to the forefront of culture; his incomparable diss track “Hit ‘Em Up” received a prime placement in the “Euphoria” Season 2 premiere and has trended multiple times on TikTok. (Most notably in 2021, when a woman assumed the role of the background singers watching Tupac fire off profanity-laced insults at the end of the track.)

However, the exhibit also arrives in a time of turmoil for the Shakur estate. Nine days before the exhibition launched, Tupac’s lone sister, Sekyiwa “Set” Shakur, filed a lawsuit against the trustee of Afeni Shakur’s estate, music executive Tom Whalley. In the suit, Sekyiwa accuses Whalley of embezzling millions of dollars while hoarding Tupac’s items she believes are now hers and failing to provide a proper fiduciary accounting.

Whalley signed Tupac to Interscope Records in 1991, making him the first rap artist at the label. After Tupac was fatally shot in Las Vegas in a case that remains unsolved, Afeni Shakur asked him to help manage the assets of the late artist, and later appointed him as manager of Amaru Entertainment, which held much of Tupac’s intellectual property, in 2015.

Sekyiwa’s name is written twice in Tupac’s museum, both times in brief while describing the family’s turbulent years in New York and Baltimore. However, she and her lawyer L. Londell McMillan believe her inherited belongings are scattered across the exhibit, particularly in the latter half where Tupac’s high-profile outfits and other possessions are featured.

“It looks like [the museum] was done very well, highly curated with a lot of Set’s personal property,” said McMillan, who represented Prince and Michael Jackson before their deaths. “It’s a sweet and sour situation. It’s great that people get to learn and see Tupac more, but the timing, presentation and curation of it should have included Set, with her personal belongings being included in the installation.”

Disputes among family members and estates after the death of an artist are not uncommon. Having a clear, concise will that all parties have agreed upon can facilitate a smoother distribution process, but even so, Jampol stresses that such arguments are “human nature” and can be almost unavoidable.

“Look what happened with Michael Jackson’s family disputes when he had a very clear will,” Jampol said. “Look what happened with Prince when he didn’t. [Disputes] are way more common than uncommon.”

Tupac didn’t leave a will at the time of his death. As such, all of his property was turned over to his mother, Afeni, who maintained ownership until her death in 2016.

According to Afeni’s trust document, Whalley was to distribute all personal property belonging to herself and Tupac, such as pictures, jewelry, clothes and cars, with one notable exception:

“Any currency or tangible personal property held primarily for investment.”

That sentence has proven to be a major point of contention.

“Tupac’s personal property obviously has value far beyond its intrinsic value,” Howard King, an attorney representing the trust of Afeni Shakur, said. “For instance, a $10 pair of used jeans by themselves are worth $10. A $10 pair of jeans that Tupac wore on an album cover might be worth $20,000. A lot of that property that was held back because of that reason is in the museum, which demonstrates that it has value beyond its intrinsic value.”

King defined items held for investment as property owned by Tupac that Whalley felt could either be in a museum or auctioned off at a substantial premium.

In the lawsuit, Sekyiwa accused the trustee of applying the exception too liberally and hiding behind it each time she asked for meaningful items.

“Sekyiwa has repeatedly requested distribution of items of personal property, much of which it is believed is of minimal monetary value, but tremendous sentimental value,” the petition reads. “Only to be told that the investment exception pertains to virtually every item of personal property owned by Afeni, including but not limited to items Afeni inherited as the beneficiary of Tupac’s estate.”

As the trustee, Whalley decided which items were defined as “investment properties” without input from Tupac’s sister. Still, King says the retention of various items was ultimately intended for the betterment of all the trust’s beneficiaries, including Sekyiwa.

“The museum is not only there to share Tupac’s legacy with his fans, it’s also to make a profit for the trust,” he said. “Every month, she gets a distribution from the trust of her share of the cash on hand not needed for other purposes. When the museum generates cash, a share of that goes to her.”

The process of determining which items have investment value, and which ones can be turned over to Sekyiwa, is still under evaluation and now will likely be determined by a judge as the lawsuit unfolds. “Heavy negotiations” between Sekyiwa and the estate have been going on for a few years, according to McMillan, who expressed displeasure at the delay.

“Tupac once said, ‘If I’m hungry and I knock on your door saying “we need some food,” and you don’t give us any, I’m gonna start knocking on that door a little harder,’” McMillan said. “‘After a while, if I’m starving, I’m gonna start kicking the door in.’ [What we’re doing is] very similar.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.