At KCON L.A., frank talk about mental health amid the ear-splitting meet-and-greets

As a teen member of the band U-KISS, Kevin Woo felt the hot glare of the K-pop limelight. His time in the band showed the California-born singer what life in the particular pressure cooker of South Korean fame meant, and how the expectations can be debilitating.

“In training, [the record labels] take a lot of privacy from you,” said Woo, now a solo artist who will appear at this weekend’s KCON convention in downtown L.A. “They take your phone away when you debut. You can’t date, which was very shocking for me. They want trainees to have a certain figure, so you’re dieting and there’s pressure to get plastic surgery.”

Record labels mold and cast band members when they’re young, and exert total control over their lives and images. That can drive you to dark places. “I’ve seen artists who have been affected by that, when you feel like you’re being watched too closely,” Woo said. “You get scared of people, of going out. You constantly fear someone taking pictures. You can’t live a comfortable private life.”

For young fans of the genre, the pressures of modern life can mirror those faced by K-pop stars. We live in a social media panopticon, where one false move can destroy your reputation. Perfection is expected. Gigantic corporations have colonized our lives.

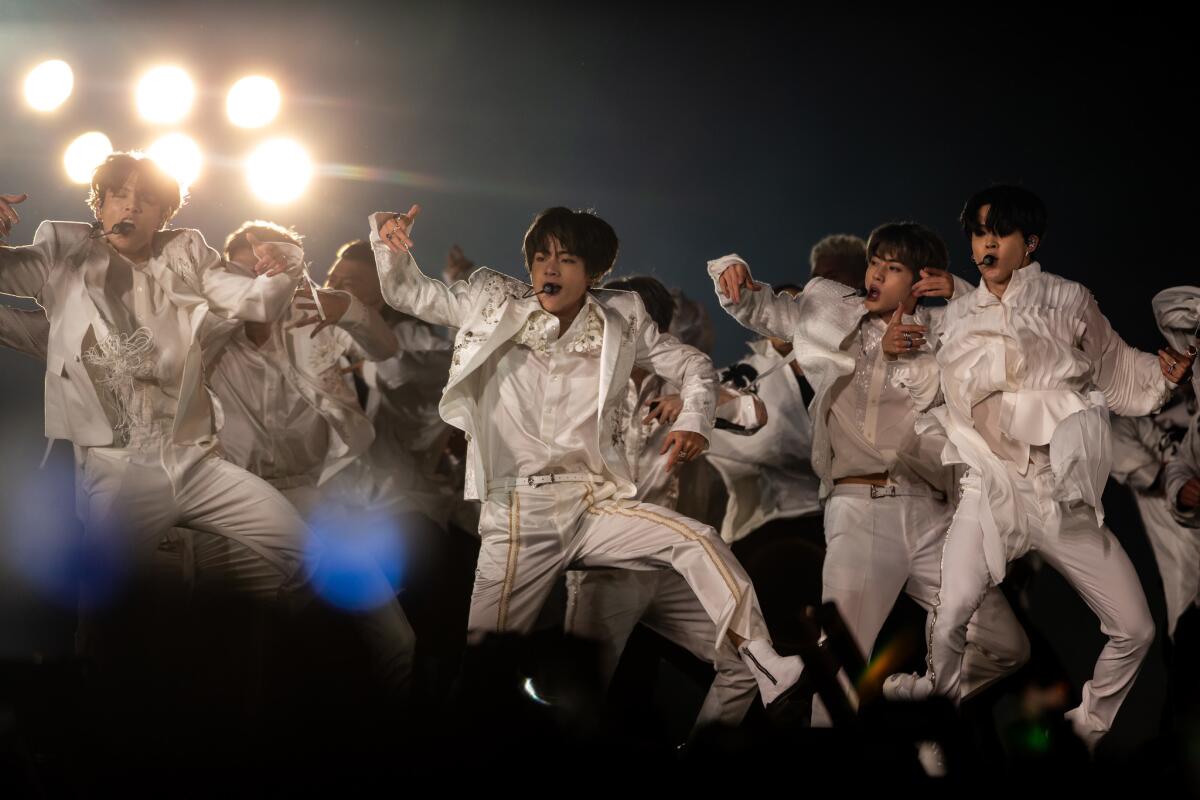

So it’s no coincidence that some of the most interesting presentations and panels at this year’s KCON L.A., a four-day concert and fan event that draws well over 100,000 people, deal with mental health issues in the scene. The main concert sports sets from rising stars like Ateez, Stray Kids and Loona, alongside a bevy of idol meet-and-greets, Korean beauty tutorials and dance workshops.

There’s immense value in the connection K-pop creates between fans, many of whom come from marginalized backgrounds. But it can also be lonely and exhausting onstage for artists in such a rigid system. Fans’ all-consuming devotion to their idols can turn threatening, both online and off-.

At KCON, fans and scholars are acknowledging that the scene is both an asset and a challenge when it comes to fans’ and artists’ mental health.

“When I was younger, I went through my own mental health difficulties, which just weren’t talked about in my culture,” said Janet Ly, a Chinese American family therapist and hallyu fan who will speak at a panel on mental health and K-pop. The scene helped her “say whatever I needed to say, and validated my experiences. There’s a strong emphasis on community because K-pop is not as mainstream in the U.S. That helps you feel connected to other people.”

But also, Ly added, “Being anonymous through a screen is scary. You only see words, not the lives being affected. They can have a great impact on somebody.”

K-pop’s rise in the U.S. elevated the scene (long established in Asia) from an internet-driven curiosity here to a thriving subculture and, finally, into a multimedia juggernaut with bands selling out stadiums and signing to major labels. With it came an ultra-passionate fan base where young audiences’ devotion to acts is unparalleled since the boy-band/“TRL” heyday of the late ’90s.

For most, that community built around outsider pop fandom is an asset. As the genre grew, events like KCON became hubs for meeting idols and one another. For a millennial generation where, in one recent study, 22% claimed they had zero close friends, that’s nourishing.

“I met my roommate, my best friend and been to weddings because of people I met at KCON,” said Shelby Moses, a KCON fan organizer and a speaker on a panel about hyper-devoted fans (or “stans”). “It created space for everyone to show up.”

Many of these fans are from racial, gender or sexual identities under threat today, and the upbeat K-pop scene is a godsend. Many of them come from cultural backgrounds (often Asian American but others as well) where mental health can be a taboo topic, or where affordable resources for treatment are scarce.

“K-pop provides space for people who have felt outside of their own communities. You hear K-pop fans say that it’s been their mental health savior, that they feel connected and supported and affirmed when they can’t find it in their own world,” said Patty Ahn, a professor at UC San Diego who studies South Korean pop culture (and who is speaking on cultural clashes at KCON).

Ahn is working on a documentary about black K-pop fans and has seen firsthand how the genre can bolster those who don’t neatly fit into any one culture.

“The fandom tracks with a lot of outsiders, be it gender or black or Latinx outsiders within their own communities, and that’s particularly compelling,” Ahn said. “I’m not sure I’ve seen that in other fandoms.”

But the pressures of fame and the fever pitch of fandom can exact its own toll.

The 2017 suicide of SHINee member Jonghyun shook the fandom and brought to light the genre’s long-standing issues around mental health. Even BTS, the biggest K-pop group in the world, admitted to similar feelings sometimes. “I really want to say that everyone in the world is lonely and everyone is sad,” BTS member Suga told Billboard after Jonghyun’s death. “I hope we can create an environment where we can ask for help.”

“Every day is stressful for our generation. It’s hard to get a job, it’s harder to attend college now more than ever,” said BTS’ RM in the same interview. “Adults need to create policies that can facilitate that overall social change.”

A lot of that pressure for idols’ constant perfection comes from the all-powerful record labels. But sometimes, it can come from fans as well.

“I turn to fans when I need support, and that always boosts my confidence. But there are fans who take it to the next level, who are too obsessive with idol groups because they love them so much they become controlling,” Woo said. “When a member messes up or has a scandal, so much bashing has a negative effect.”

The kind of harassment that can happen in K-pop has echoes of the same stalking dynamics, both physical and digital, that many young people, especially young women, face in their own lives.

“There are a lot of instances of people hunting down idols and breaking into their hotels. BTS had a plane delayed because people bought tickets just to take pictures of them,” Moses said. “We saw how deteriorating that can be — there have been suicides. It’s really sad.”

Moses has had to moderate her own fandom to avoid harassment over the years. “You see a lot of bullying for very stupid reasons,” she said. “My friends and I used to do K-pop cosplay with elaborate outfits, and got bullying and death threats after someone posted pictures of us. We were like, ‘OK, this has changed,’ and we backed out of that scene.”

Many fans were hurt and disillusioned by the still-ongoing Burning Sun scandal, which implicated several high-profile K-pop stars and industry figures in a ring of sex crimes. Charges included allegations of clandestine videotapes of assaults at a popular Seoul nightclub shared over text-message chains.

The scale and sordidness of that scandal pulled back the curtain on the image of squeaky-clean K-pop idols. But fans still wrestle with what that means for their own attachments and communities. At best, it opens up space for fans to be candid about their own experiences with abuse. But time will tell if the scene is ready to listen.

“We have so much emotionally wrapped up in music and a sense of belonging to it. This is a time where we need to be open and have space for dialogue,” Ahn said. “Idols and celebrities need to be held accountable,” Ahn added, mentioning Seungri, a central figure charged in the Burning Sun scandal. “Idols have a tremendous amount of power and it’s getting difficult to hold any ambivalence. You can love an idol but have complicated feelings.”

Underneath the shiny veneer and tight corporate control of K-pop, profound pain and abuse can boil over. Now that K-pop has matured in the U.S., most in the scene are glad that more difficult conversations are finally happening in public. It’s not as jubilant as a new Blackpink single, but it might be more important.

“I like the awareness that it’s not just happiness and sunshine and rainbows,” Ly said. “They’re people too, they make mistakes and struggle. They’re humans but very famous humans.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.