Oscar Picks

Justin Chang's Dream Ballot

I think “Drive My Car,” the much-acclaimed drama from Japanese writer-director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, is the best picture of 2021. I’m not alone.

A quietly transcendent road movie about life, art, grief and desire, exquisitely elaborated from a Haruki Murakami short story, “Drive My Car” has become the year’s runaway critical sensation. The reviews have been ecstatic, the top-10 placements unceasing. The movie is heavily favored to win the international feature prize at the Oscars in March, though some of us wager it deserves more than a consolation prize. Several top critics’ organizations — including the New York Film Critics Circle, the Boston Society of Film Critics, the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn., the National Society of Film Critics and the Toronto Film Critics Assn. — have already named “Drive My Car” the year’s best film. Not the best international film, but the best film, period.

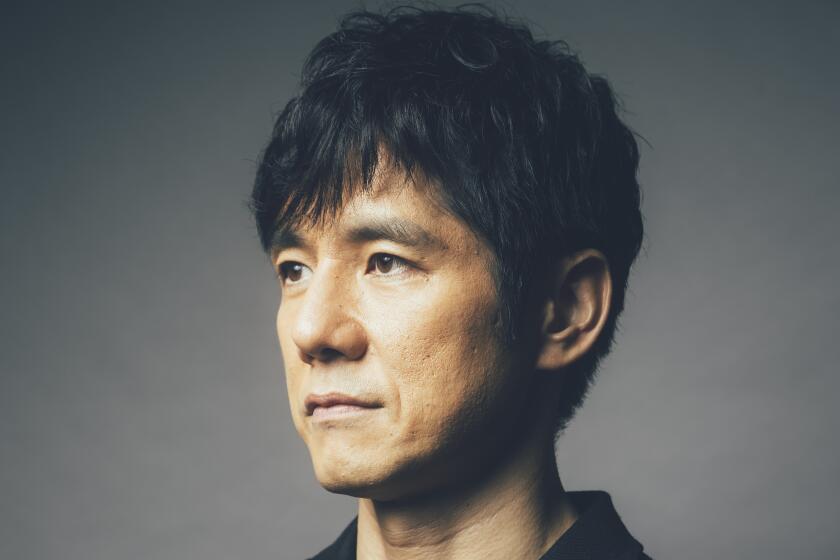

This remarkable consensus has taken many by surprise, including some of us who helped engineer it. (I’m a voting member of LAFCA and the NSFC; both groups, along with the NYFCC, have a number of members in common.) “Drive My Car” may be a masterpiece, but masterpieces go overlooked every year. And while the 43-year-old Hamaguchi has been one of the most exciting new talents on the film-festival scene for some time now, he is still unknown by many American journalists and moviegoers. Despite a handful of acclaimed works including “Happy Hour,” “Asako I & II” and “Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy,” he doesn’t (yet) have the profile of Alfonso Cuarón, Pedro Almodóvar or Bong Joon Ho — all household-name auteurs whose films have been embraced by critics and, to varying degrees, by members of the motion picture academy.

Which is why it’s been gratifying to see so many critics nod in agreement that a hypnotic three-hour Japanese talkathon might be the year’s best movie. And this has been a year with no shortage of candidates for that title, from established masters like Jane Campion (“The Power of the Dog”), Paul Thomas Anderson (“Licorice Pizza”) and Steven Spielberg (“West Side Story”); from superb actors turned superb directors like Rebecca Hall (“Passing”) and Maggie Gyllenhaal (“The Lost Daughter”); and from other great filmmakers from overseas, including Almodóvar (“Parallel Mothers”), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (“Memoria”), Céline Sciamma (“Petite Maman”) and Joachim Trier (“The Worst Person in the World”).

Amid such estimable competition, how did “Drive My Car” become the default consensus choice among critics?

As ‘best movie of the year’ prizes pile up, including a shout out from former President Obama, director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi explains ‘Drive My Car.’

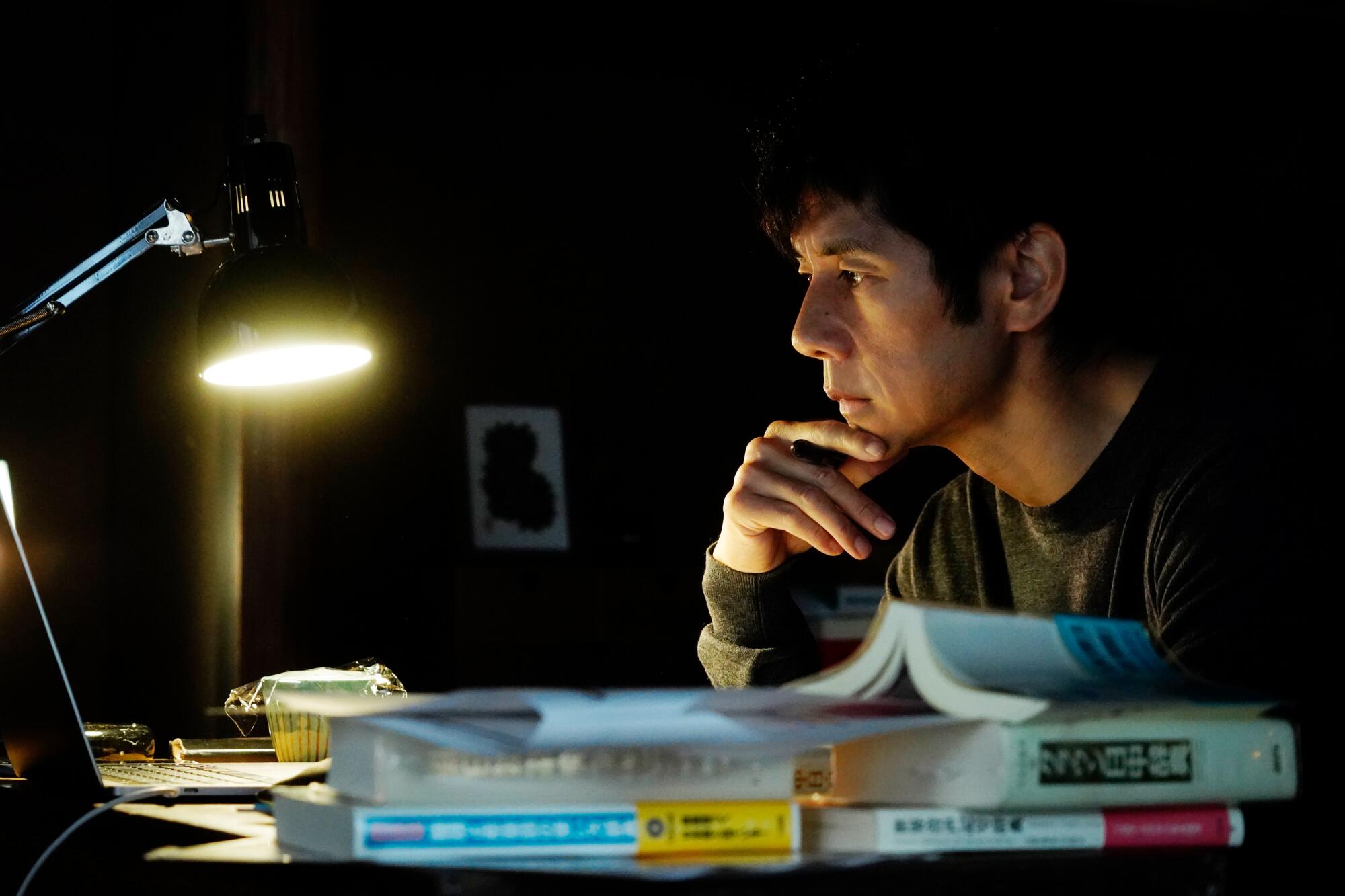

I think it has something to do with the subtly disarming nature of Hamaguchi’s achievement and the beauty of his movie’s contradictions. “Drive My Car” is a three-hour drama that seems lighter and fleeter than some two-hour ones. In telling the story of a bereaved theater star (played by the brilliant Hidetoshi Nishijima) and his unexpectedly cathartic odyssey through a fresh staging of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya,” Hamaguchi has made a movie that feels literary but never fusty, that wears its intellectual heft with lightness and grace.

The director grapples with themes that are not exactly uncommon in fiction — the unshakable nature of grief, the porous boundaries between life and art — and excavated such powerfully specific insights, sans even a whisper of banality or cliché, as to make them feel like uncharted territory. And he’s made a movie about the slippery nature of acting that appropriately features the year’s finest ensemble, with richly nuanced, perfectly harmonized performances from Nishijima, Tôko Miura, Reika Kirishima, Masaki Okada and Park Yoo-rim.

Working with director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi was a new experience, the actor says, especially when he rode in the trunk of the car.

“Drive My Car” is lucid but mysterious, delicate but concrete; it’s a work of rigorous realism that unfolds like a dream. (In this respect, it can’t help but recall Lee Chang-dong’s “Burning,” the other great Murakami adaptation of recent years.) It’s the rare movie that can bring together seemingly incompatible schools of critical thought: Formalists can marvel at the unshowy mastery of Hamaguchi’s technique and the novelistic richness of his screenplay (co-written with Takamasa Oe), while humanists can simply soak in a wise, wrenching story that keeps finding new ways to open you up emotionally, that keeps deepening — rather than numbing or exhausting — your capacity to feel.

If I’m being a bit presumptuous about my colleagues’ tastes, I’m a bit more hesitant to rationalize the motives of academy members, though that hasn’t stopped me from optimistically wondering if they might give “Drive My Car” a whirl — and give the movie not just its expected due in the international feature race, but also the Oscar nominations it deserves for best picture, director, lead actor (Nishijima) and adapted screenplay. If that’s too tall an order, let’s just focus on the big one: best picture, a category that will feature a generous 10 nominees this year. You’d think that one of those nominees would be the year’s most widely acclaimed movie.

Only five other movies — “Goodfellas,” “Schindler’s List,” “L.A. Confidential,” “The Hurt Locker” and “The Social Network” — have ever pulled off the Big Three critics’ sweep, winning best picture from the New York Film Critics Circle, the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. and the National Society of Film Critics. All five were nominated for the best picture Oscar; two went on to win. If that precedent has any meaning, surely “Drive My Car” should now be cruising to a best picture nomination. (And speaking of cruising, hell, it even has one of Oscar’s favorite narratives: characters bonding over car rides. Just minus the genteel racism!)

Statistics and precedents are meant to be defied, of course, especially those rooted in something as mercurial as movie taste. Still, it’s worth asking: What, exactly, is keeping “Drive My Car” from being taken seriously as a potential best picture nominee? Why is it still stuck in neutral on awards prediction sites like Gold Derby or even the Times’ own BuzzMeter, where it’s precariously positioned at No. 10? (Without my own highly optimistic placement of the film at No. 1, its ranking would surely be lower.)

This emotionally overwhelming adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short story confirms Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s standing as one of the most exciting filmmakers working today.

We can point to the movie’s relatively low profile and limited exposure, but robust commercial performance hasn’t been a best picture prerequisite for years, and it feels even less so in an era of COVID anxiety and streaming domination. We can float theories about how Oscar voters never listen to critics, which is of course ludicrous, and not just because well-reviewed movies get nominated for Oscars all the time. I personally suspect that awards voters look to critics for guidance and affirmation far more than they like to let on, and that by the same token, a lot of critics care a great deal more about the Oscars — and their small but not exactly negligible ability to sway the field — than they care to acknowledge.

I don’t mind acknowledging it myself. I’m always invested in what the Oscars choose each year, partly because I’m aware of the good they can do — the stereotypes they can dismantle, the artists they can spotlight, the filmmakers they can lift up — on those occasions when they get it right. I’m also easily irritated when a superior work of art like “Drive My Car” gets undersold to voters for reasons that have nothing to do with its quality or even its ticket sales, but rather its perceived foreignness: its Japanese setting, its Japanese actors and its reams of Japanese dialogue (plus a few other spoken languages to boot). Hamaguchi’s movie risks being sidelined by a reflexive assumption among too many Oscar voters and Oscar watchers: namely, that when we talk about “best picture,” what we really mean is “best American picture” or “best English-language picture.”

There have been encouraging signs that this assumption is beginning to wane. For the better part of its 95-year history, the academy has been as reliably Amerocentrist, xenophobic and flat-out racist as the industry it represents, but in recent years it has also taken sincere, laudable steps to diversify its voting ranks. The academy of 2022 is a better, smarter and more international organization than it’s ever been and clearly wants to be perceived as such. This is the academy, after all, that handed the best picture Oscar to “Parasite” two years ago, opening the gates for presumably more terrific movies from overseas to follow in its footsteps. “Drive My Car,” needless to say, isn’t “Parasite.” And it shouldn’t have to be “Parasite” to be taken seriously by an organization that prides itself on discernment.

What would the Oscars look like if the academy — and the journalists who cover it — began each awards season by regarding the worthiness of movies from other countries not as an exceptional circumstance, but as a basic, uncontroversial given? In a resurgent, all-around exceptional year for world cinema, “Drive My Car” should hardly be the sole beneficiary: What if movies as smart, tender and moving as “Parallel Mothers,” “Petite Maman” and “The Worst Person in the World” were legitimately in the best picture conversation? What if “Parallel Mothers’” Penélope Cruz (not exactly an obscure name) were being as hotly tipped to win a second Oscar as Nicole Kidman or Olivia Colman, rather than being relegated to the buzz void typically reserved for non-English performances? What if the justly vaunted Campion, hardly the sole female filmmaker of note this year, were joined in the directing race by Joanna Hogg (“The Souvenir Part II”) or Julia Ducournau (“Titane”)?

To hear it from some people, these are pretentious, elitist suggestions, the latest evidence of how woefully out of touch critics are with the broader tastes of the academy and the larger moviegoing public. Contempt for critics is nothing new, and nothing you should trust me to be impartial about. Still, I’d be remiss not to note that the cynical, faux-populist thinking that’s degraded so much of our political discourse in recent years, elevating xenophobia and anti-intellectualism into core principles, seems to have taken similarly ugly root in the way a lot of people regard and respond to art. (Witness the hysterical overreaction in some online circles to the fantasy Oscar ballots published by the New York Times’ Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott, who had the gall to suggest that superb, under-the-radar movies like “Azor,” “Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn,” “Memoria,” “The Velvet Underground” and, yes, “Drive My Car” might actually merit serious consideration.)

Personally, I try to to steer clear of words like “elitist,” an insult that has a curious way of rebounding on those who use it. It’s odd being accused of elitism by those who think a list of awards picks should be populated exclusively by American and British celebrities. Given Hollywood’s annual orgy of self-love and its reflexive assumption of its own cultural superiority, isn’t it the opposite of elitism to recognize artistic excellence from countries like Japan, France, Colombia and Romania? Isn’t it, in fact, a downright egalitarian gesture? Shouldn’t an institution that claims to champion inclusion and representation acknowledge the greatness of cinema in any culture, any language?

Which brings us back to “Drive My Car,” whose most emotionally overpowering scenes are built, tellingly, around an experimental theater production of “Uncle Vayna” in which the performers are all acting in different languages. Under these highly conceptual circumstances, real communication would seem impossible; miraculously, the opposite turns out to be true. As the actors converse in a mix of Japanese, Mandarin, Korean and Korean Sign Language, bonds form, epiphanies bloom and a small, profound idea rises to the surface: As human beings, we are united by more than a shared tongue, and the language of art is a universal one. The best plays understand this. The best movies too.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.