Behind the scenes on the ‘surreal nightmare’ within ‘1917’

- Share via

Every scene in Sam Mendes’ “1917,” about two young British World War I soldiers on a lifesaving mission across enemy lines, presented a range of logistical and technical challenges to its filmmakers. The reason, on the first page of the script by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns, is how the action unfolds, breathlessly moving through what appears to be a single, uninterrupted take. Scenes were mapped out, modeled, choreographed and endlessly rehearsed as the sets took shape.

Midway through the film, however, comes an intentional break in the shot when Lance Cpl. Schofield, played by George MacKay, gets the lights knocked out of him. When he comes to, he stumbles out among a French village’s blazing ruins, military flares punctuating the night sky.

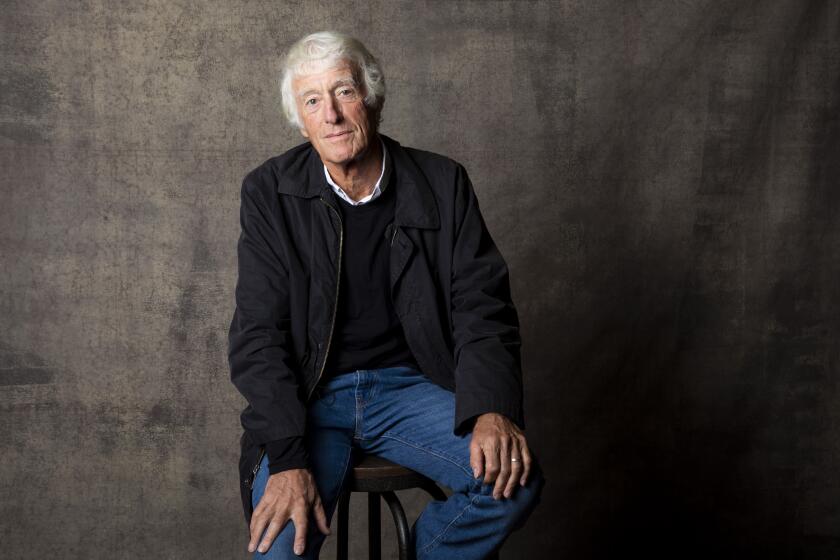

We asked cinematographer Roger Deakins and production designer Dennis Gassner, who worked together with Mendes on “Jarhead” and later on Bond films, to describe how the scene evolved and what they did to bring that vision to the screen.

The World War I film ‘1917’ presents its action in seeming real time, with the fluid camera movements always connecting to the characters on a mission

Deakins: Sam and I spent several months just talking about how to visualize the film before anything else started happening. We did storyboard a helluva lot of it, but I don’t think many people saw the storyboards in the end. But they were a way for us to explore the kind of cinematic language we wanted to use, the kind of relationship between the camera and the actors. In this sequence, we talked a lot about how it is the one cut in the movie, but at that point, we wanted it to be almost hallucinatory, like a surreal nightmare. Schofield wakes up, but is he or isn’t he actually awake? Is he alive or dead? That’s what I think Sam was after with the fire and the flares going overhead. You wanted it to feel like this was hell but also somehow poetic.

Gassner: I’ve learned that it takes a lot of discussions and analysis of imagery and narrative when designing a set. When I first read the script, I knew this wasn’t a story about the war. It’s a story about the human condition. And that idea manifested itself, inch by inch, for three months of eight to 10 hour days, measuring, organizing and finding places we could do all this within England and Scotland. The way to approach the design, from my experience, then, was through the art of war, and this midway point in the film clearly is a transcendent moment despite its horror. Schofield arrives at this place and pauses because it’s extraordinarily primal, because fire is the essence of human survival.

Oscar winner Sam Mendes and co-writer (and “history nerd”) Krysty Wilson-Cairns got into the trenches for “1917,” an immersive World War I quest movie.

Deakins: The thing that is quite key to the scene was how we were going to go from the cut and open with Schofield waking up. Sam and I agreed that we never wanted the camera to go back on itself; we always wanted it to keep moving forward. So when he wakes up on the steps, he would have gone down the steps to go out. We thought instead of going down the steps, which we didn’t want to do, why doesn’t the camera just go past his POV, see the dead German soldier and then float through the window? We felt that was OK in that moment, but in the rest of the film, we didn’t want to detach the camera from the characters. Here we felt we earned it, especially because it was a bit of a dreamscape he was entering into.

When the camera, which I’m controlling remotely, comes out the window, it’s on a crane that’s coming through the window. The set was built so the window parts as the camera gets close to it. Another crane on the ground takes over the camera up at the window height and comes down. Then it’s taken off by the grips, who are now hand holding it and starting to run behind Schofield as he’s running into the town. Schofield drops to the ground, the grips run around him with the camera, then get into a vehicle, which is now tracking back as he gets up. The camera went from the cranes, to a Steadicam and an ARRI Trinity rig and, at one point, when he runs from the schoolhouse after killing the German through the outskirts of town, onto a motorbike.

We thought it would be a great way to introduce the town out of the window, then gradually close in on it and have Schofield walk under the camera, and off we go again. Our Steadicam operator Pete Cavaciuti even invented a system to mount this stabilized head so the camera could shoot over his shoulder as he ran with it. That’s something I haven’t seen done before.

Gassner: We created everything from scratch and started with a model of this scene. Everything you see was physically manufactured with only a few set extensions and cleanup in CGI. It was fairly late in the development of the town, for example, that we decided on the idea of the colonnades as you go down the main street. It was always something that just evolved. It was an extraordinary thing to try to pull off but that’s what we all wanted to do to show people it’s possible to still make films that aren’t entire green screen fantasies.

Deakins: This whole section, including the discovery of the young woman and baby in the basement, was probably the most complicated piece of lighting for the entire film. It took a long time to figure out how we wanted to deal with the light and the shade. Because it’s lit by so few sources (and we had a full moon to contend with during shooting), it was very important what the structure of the broken walls was. Some places you’d have light and some would be in darkness.

The timing of the flares was also very complicated, combined with the light from the burning church, which was another huge lighting rig. I did a lighting test to figure out how to do the flares, to see what shadows I could use. I was worried about the variable light of actual flares, so our special effects supervisor Dom Tuohy figured out how to do it with a big lighting rig we could digitally control by rigging the flares off wires on cranes. We mapped out where we wanted the flares to go on the art department’s model of the town using little LEDs. Then we needed to build a structure to cast shadows from the flares as well. There were six cranes and each flare had its own track and lasted a certain number of seconds. It was quite amazing what he did.

Gassner: The clock was always ticking. Time was our enemy in every way, not just for the two soldiers on screen. But the quality of the team that came together was extraordinary. That’s what designing a film is. When I hit the deck and Roger (who I’ve known and worked with for 28 years) hit the deck, we’re both running as fast as we can. And we did that for the entire film.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.