Indie Focus: The scuzzy, tender and shocking ‘Titane’

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

One of my favorite festivals in Los Angeles is Beyond Fest, the high-energy genre festival that is always full of surprises and discoveries. This year’s in-person festival is already underway, having opened with the West Coast premiere of “Titane” — see more on that below — but still with plenty to come, including tonight’s U.S. premiere of David Gordon Green’s “Halloween Kills.” The festival continues through Oct. 11.

Other Beyond Fest highlights include a double bill of “Thief” and “Collateral” with filmmaker Michael Mann in person, the U.S. premieres of Dasha Nekrasova’s “The Scary of Sixty-First” and Lucile Hadžihalilovic‘s “Earwig,” the West Coast premieres of Gaspar Noé’s “Vortex,” Jim Cummings’ “The Beta Test,” Scott Derrickson’s “The Black Phone,” the new restoration of Andrzej Žulawski’s “Possesion” and the closing night world premiere of Scott Cooper’s “Antlers.”

It continues to be a busy time of existential uncertainty for the industry of Hollywood itself. Anousha Sakoui had an interview with IATSE President Matthew Loeb about the very real possibility that the union’s roughly 60,000 members may soon go on strike, which could bring production of film and television to a standstill. As Loeb said: “Our goal is to reach an agreement, not have a dispute.”

Ryan Faughnder wrote about the pending acquisition of talent agency ICM by rival company CAA, further consolidating behind-the-scenes power in the industry. Ryan also covered the settlement in the high-profile lawsuit between Scarlett Johansson and Disney over her compensation for “Black Widow.” Terms were not disclosed.

And playing at the Nuart is a new 4K restoration of Joan Micklin Silver’s delightful 1975 debut feature “Hester Street,” a tale of Jewish immigrants in 1890s New York City that earned Carol Kane an Oscar nomination for best actress at age 23. This is a rare chance to see the movie in a theater and not one to be missed.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

‘Titane’

Written and directed by Julia Ducournau, “Titane” made Ducournau only the second woman in the history of the Cannes Film Festival to have directed the winner of the prestigious Palme d’Or. And while that is notable enough, that it was for a film this relentless feels all the more remarkable, an arthouse exploitation shocker with a scuzzy, tender heart. Fairly early in the film, a female serial killer becomes impregnated by a car. On the run, she hides out by posing as the long-missing son of a fireman. Portrayed by Agathe Rousselle and Vincent Lindon, they each discover more about their sense of self and capacities for love. The film is playing now in general release.

For The Times, Justin Chang wrote: “‘Titane’ is nothing if not a triumph of engineering, to the point where the slickness and sophistication of its technique sometimes threaten to overwhelm the rigor of its ideas. Still, it’s hard not to admire the sheer verve with which Ducournau ultimately welds those ideas together. ‘Titane’ is an essay, etched in rivulets of blood and oil, on the mutability of gender and the pliability of desire. It’s also a profane hymn to the specific alchemies of fire and metal, to the dark allure of forces that can destroy us no matter how hard we try to bend them to our will. And finally, perhaps, it’s Ducournau’s attempt to turn that very destruction into a creative act, to envision the world collapsing in an unholy trinity of flame, chrome and flesh — and to pull an improbable and singularly incandescent love story from the wreckage.”

I spoke to Ducournau for a story that will be publishing soon, a guided tour through the influences on the look and storytelling of the film, everything from Caravaggio and “1917” to Nan Goldin and “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” (But not, it should be noted, David Cronenberg’s “Crash.”) As to whether she considers herself a genre filmmaker, Ducournau said: “I use the grammar of body horror for sure. I like to divert the codes of horror, to divert the expectations of the audience. A lot. … So I consider definitely myself as a genre filmmaker, but I would like to say genres, plural. For me, it’s really about playing with all the tools and all the codes that are at my disposal, in the spectrum of human psyche and human emotions and try to somehow bend them all together.”

For the New York Times, A.O. Scott wrote: “‘Titane’ consolidates a filmmaking style based on visceral shock, grisly absurdism and high thematic ambition. Violence is often played for comedy. Cruelty collides with tenderness. Eroticism keeps company with disgust. Through the stroboscopic aggression of Ducournau’s images you can glimpse ideas about gender, lust and the intimacy that connects people and machines. … It’s no wonder that those concerns don’t entirely cohere, given Ducournau’s furious sensationalism. The hectic, brutal intensity that drives the first part of the movie, before Alexia becomes Adrien, dissipates in the middle, as the narrative engine sputters. The pregnancy supplies some suspense, of course, but the situation becomes curiously static, and the provocations increasingly mechanical. For all its reckless style and velocity, ‘Titane’ doesn’t seem to know where it wants to go.”

For the Playlist, Jessica Kiang wrote: “Ducournau’s follow-up to her sensational debut ‘Raw,’ is roughly seven horror movies plus one bizarrely tender parent-child romance soldered into one machine and painted all over with flames: it’s so replete with startling ideas, suggestive ellipses, transgressive reversals and preposterous propositions that it ought to be a godforsaken mess. But while God has almost certainly forsaken this movie, He wouldn’t have been much needed around it anyway. Ducournau’s filmmaking is as pure as her themes are profane: to add insult to the very many injuries inflicted throughout, ‘Titane’ is gorgeous to look at, to listen to, to obsess over, and fetishize.”

For Artforum, Beatrice Loayza wrote: “‘Love is a dog from hell’ reads a tattoo on Alexia’s sternum, a reference to the title of Charles Bukowski’s 1977 poetry collection and a billboard-subtle announcement of the film’s glib through line: Love — real, unconditional love, the kind that throbs — is f— up, man. I put this prosaically because Ducournau’s calculus is comparably insipid, a parade of superficially radical iconography that draws its power from the cobbling together of liminal experiences and opposite extremes. ‘Titane’ is certainly a joyride, but truly unhinged it is not, circumscribed as it is by its own autophiliac enthrallment to extremity. Once you access its wavelength, the ride quickly begins to feel numb.”

‘El Planeta’

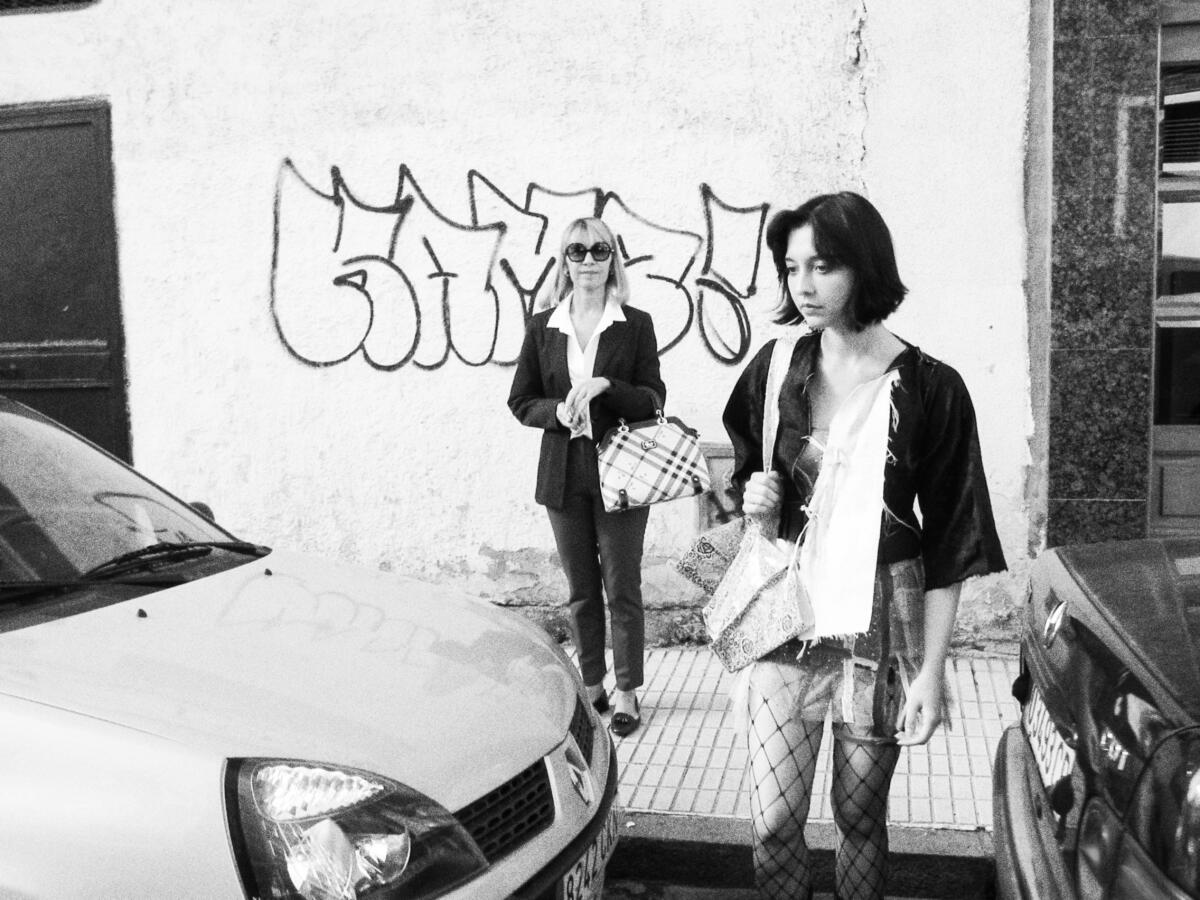

Written and directed by Amalia Ulman, “El Planeta” also stars Ulman alongside her actual mother, Ale Ulman, as Leonor and María, a mother and daughter who are quickly running out of money. Facing eviction from their apartment, they get by pulling small-scale scams wherever and whenever they can, running up tabs at restaurants and buying designer clothes on credit. The movie is playing at the Landmark Westwood.

For The Times, Carlos Aguilar wrote: “Tonally intricate, though in places too engineered to amp up the quirkiness, the escalating stakes highlight the profundity of the women’s solidarity in their shared woes. … Taken from a restaurant the mother-daughter duo frequent, the name “El Planeta” seems to speak closely to the characters’ crumbling personal universe. Leo and María — and judging from their on-screen rapport, Amalia and Ale as well — spin on a wavelength where their irrational lifestyle and coping mechanisms are logical to their comprehension; we are only lucky to be invited to visit this two-people planet for a short while.”

I spoke to Amalia Ulman back when the film premiered earlier this year at Sundance. A fine artist making her feature debut with the film, she said of the two characters and their seeming obsession with status, “I think it’s not like they’re personally obsessed with it, but that’s the only thing they have left. Because their bodies are the only thing they have left. They’re about to lose [the mother’s] home in two months. They don’t have any money. They don’t have anything except themselves. And how they present themselves to the world is the last resource that they have. The mother is broke, but the only way that she can get some groceries or not be suspicious if she shoplifts is by her appearance. So I didn’t see it so much an obsession, but more like a survival mechanism that women have when they don’t have anything left. It’s like, that’s the last thing you have.”

For the New York Times, Teo Bugbee wrote: “This is a dry comedy that elicits amused recognition rather than belly laughs, and Ulman, as a first-time feature director, makes canny decisions to set a wry tone. The movie was shot in black and white, and music is used sparingly. Even when Leo and her mother present an appearance of opulence, with bespoke gowns and designer T-shirts, they remain visually trapped in a world of austerity. Like its grifter characters, ‘El Planeta’ signals luxury but it does not luxuriate, creating an experience that is more intellectually than sensually satisfying.”

For IndieWire, Eric Kohn wrote: “Despite little indication that the pair can escape eviction, María seems to live in an exuberant bubble of denial, surrounding her home with various cat paraphernalia and fiddling with her phone while her daughter attempts to keep the hustle alive. It’s both endearing and sad to watch them drift along to the inevitable repercussions for María’s reckless behavior. … And it finally arrives at an understated payoff in the closing moments that completes the big picture with a scathing punchline that puts the whole thing in perspective. More than anything else, the appeal of ‘El Planeta’ comes down to people who realize they’ve exhausted every option, and decide they may as well go down in style.”

‘The Many Saints of Newark’

Directed by Alan Taylor from a screenplay by David Chase and Lawrence Konner, “The Many Saints of Newark” is a prequel to “The Sopranos,” telling the story of how young Tony Soprano (played by Michael Gandolfini, son of the late James Gandolfini) fell under the tutelage of Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola) and learned the ways of a life of crime. Featuring younger versions of various other characters from the beloved series, the cast also includes Vera Farmiga, Ray Liotta, Jon Bernthal, Cory Stoll, Billy Magnussen, John Magaro and Leslie Odom Jr. The film is now playing in theaters and streaming on HBO Max.

For The Times, Lorraine Ali wrote: “Too bad Dickie feels more like an echo of future Tony than the beginning of a new, revealing origin story. … There’s a lot jammed into these two hours, with too many diverging narratives, truncated subplots and series tie-ins competing with the surrogate dad relationship between the gangster and young Dickie — the very sell of the film. It leaves little space for their connection to make deeper inroads.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote: “Movie spinoffs can be tough to pull off. Nothing felt at stake when I watched, oh, the first ‘Brady Bunch’ movie, but its source material wasn’t a critical fetish, something that inspired excited discussions on masculinity, the latest golden age of television and the effect on the industry. “The Sopranos,” though, was too good, too memorable, and its hold on the popular imagination remains unshakable. It still casts a spell, and the movie knows it, which is why it sticks to the tired template of a boy’s own story rather than taking a radical turn, like revisiting Tony’s world from Giuseppina’s or Livia’s or Harold’s points of view. In the end, the best thing about ‘The Many Saints of Newark’ is that it makes you think about ‘The Sopranos,’ but that’s also the worst thing about it.”

For the Washington Post, Inkoo Kang wrote: “‘The Sopranos’ was about a group of middle-aged mobsters nostalgic for an era of manly invincibility and self-sacrificing loyalty that probably never existed. ‘Make the mob great again’ was practically Tony and his crew’s unofficial slogan. “Many Saints” unnecessarily confirms the wrongheadedness of their illusions: Tony’s elders were just as ruthlessly petty and even more viciously sexist and virulently racist than his generation. … A sourness in tone keeps the proceedings from achieving the series’ signature black wit, adding to the film’s ungainliness. Alternately claustrophobic and epic compositions can’t make up for the myriad story lines (including one frustrating red herring) and pacing issues that periodically lose sight of the stakes at hand. At least there’s no shortage of manicott’ to console us when ‘Many Saints’ doesn’t answer our prayers.”

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.