A scholar’s inspiration for a book on racial injustice: Her brother’s life sentence

On the Shelf

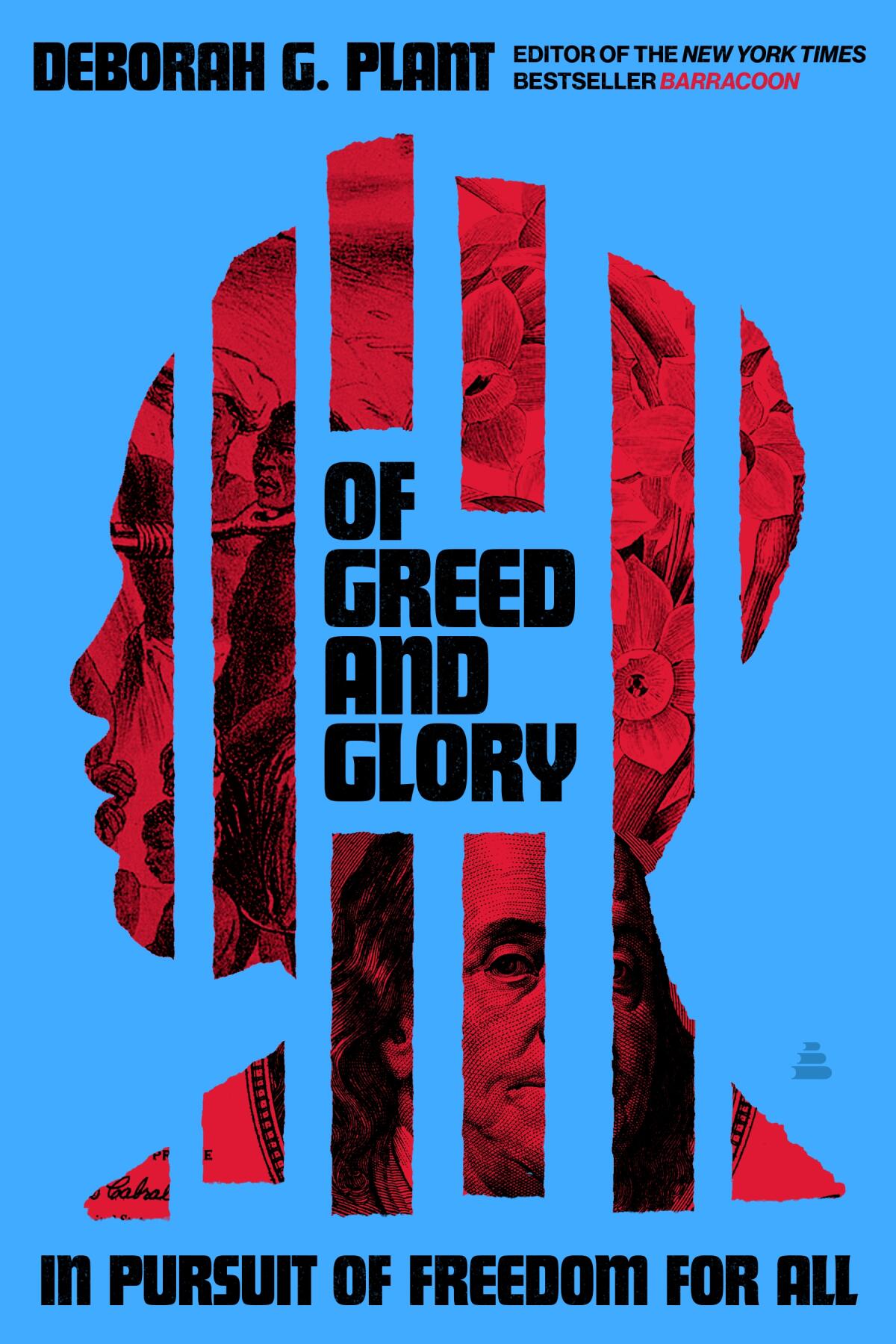

Of Greed and Glory: In Pursuit of Freedom for All

By Deborah G. Plant

Amistad: 288 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 2016, Deborah G. Plant took on the job of editing an unfinished manuscript by Zora Neale Hurston, one of the most beloved figures in African American literature. Many editors might have been intimidated, but having studied and taught Hurston’s work for decades, Plant was well prepared. The resulting book, “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo,’” became a New York Times bestseller and landed on many lists of 2018’s best titles.

Plant’s work on that manuscript inspired her new book, even though it’s much more contemporary — and much more personal. “Of Greed and Glory” centers on the criminal-justice system and on the experience of Plant’s brother, Bobby, a longtime inmate at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Much like the work of Michelle Alexander and Douglas Blackmon, Plant’s narrative traces connections among slavery, the Jim Crow regime and modern mass incarceration.

But “Greed and Glory” also expands into the domain of late capitalism, examining how the “master-slave” dynamic is also at play in modern workplaces — from the company-provided laptops and phones that can “function like the electronic ankle bracelet of someone under house arrest” to the media products that keep us pacified. Its analysis also reaches into the realms of the psychological and the spiritual, territories where Hurston herself would no doubt have been comfortable.

Even as a backlash brews over teaching America’s racist history, ‘Forget the Alamo’ and ‘How the Word Is Passed’ tell of the full, inglorious past,

Over the last 10 or 15 years, there’s been a lot of literature and other media connecting the legacy of slavery with the justice and carceral systems. What did you want to bring to that discussion?

Well, in a way the book reinforces what has been said and continues it. Sometimes it’s not enough to say something once. If we were living in a just society, where the justice system did not use unjust practices to enthrall us, then we could just find something else to talk about. But this is not the case.

However, the book also adds to the conversation by looking at two things. First, my brother’s story shines light on certain particulars. I think about what Ta-Nehisi Coates says in “Between the World and Me”: that slavery is not just this mass of flesh; it involves the dehumanization of an individual woman, an individual man, an individual child. The same is true with mass incarceration. My brother’s voice illuminates certain aspects of what happens to us when our dignity as human beings is dismissed.

But I have also tried to look at the essence of enslavement. It’s not just about some chains that we hear clanking; it’s not just about a prison system, and it’s not just about Black people or poor people. When we understand the dynamics at the core of it, then we can begin to see how it manifests in our own lives.

Tell us about your brother and how he ended up at Angola.

I have seven siblings — my mom had 10 children, but eight of us survived — and I’m somewhere in the middle. We were reared in Baton Rouge. My brother is four years younger, but he always acted like a protective older brother. When I left home to go to [college] and I would return home, he would organize these house parties for me, or he’d fix me gumbo or red beans and rice.

In 2019, journalist Ben Raines helped find the Clotilda. He discusses his book, “The Last Slave Ship,” and the triumph and tragedy of its descendants.

As you say in the book, his girlfriend accused him of abuse and rape. I’m sure this was a difficult matter to write about. He admitted to hitting her but refused to plead guilty on the rape charge, so he was put on trial and convicted — in spite of what you say is compelling evidence that he wasn’t guilty. He was sentenced to “life at hard labor,” then refused parole.

Yes, my brother was physically abusive. That was horrendous, but it wasn’t the only factor. If my brother and my dad had mortgaged the house to get a private attorney, my brother might have been freed from that abuse charge as a first-time offender. But we have a system that allows DAs to offer plea bargains where they coerce defendants to confess to crimes they haven’t committed in order to avoid being charged with greater crimes. When you refuse that “bargain,” you have the book thrown at you.

And in his case, that meant a life sentence. He’s been at Angola since 2000.

Yes. But as I say in the book, a person is never incarcerated alone. Their whole family, in a way, goes to prison. And the money that is being earned does not go to that person’s family or community. But I also want to connect my brother’s experience with the broader trend of objectifying the American worker. Just as enslaved people were considered property — and my brother, and his labor, are seen as the property of Angola — corporations seem to look at those who labor in their factories, or in offices, also as property. Less and less are they treated as human beings.

You’ve spent your career studying and writing about literary figures, including Hurston and Alice Walker. How has that shaped the perspective of this book?

I became interested in both of those writers because they learned to live in the world on their own terms. They embodied the ideals of freedom. Walker was interested not only in the freedom and survival of her people, but in their survival as whole people. She talked about living with memories of tragedy and grief, but also preserving the capacity for creativity and joy.

This is so with Hurston as well. When she looked at Black Southerners in the Jim Crow era, rather than seeing a demographic that was pathological and deprived and impoverished, she saw the greatest cultural wealth on the continent. So both of these writers can help us to see ourselves through our own eyes.

‘Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space,’ PBS’s new ‘American Experience’ documentary, reveals a complicated early champion of the Black experience

There’s more awareness these days of the ways we’re still living with the consequences of slavery and Jim Crow. I think there’s also more awareness about the toll of mass incarceration. But do you think that has produced meaningful change?

I agree that awareness has grown — and awareness is very important. If our consciousness can shift, it can ultimately lead to changes in our actions. Unconsciousness is the taproot of these various kinds of enslavement we experience today.

But politically, one of the changes that really stands out for me is that four states have changed their constitutions to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. There has also been an effort in Congress to change the 13th Amendment to take out the criminal punishment exception. These are movements in the direction of universal freedom.

Tabor is a journalist and the author of “Africatown: America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.