‘Be your own role model’: What one Black UC Irvine astrophysicist had to overcome

- Share via

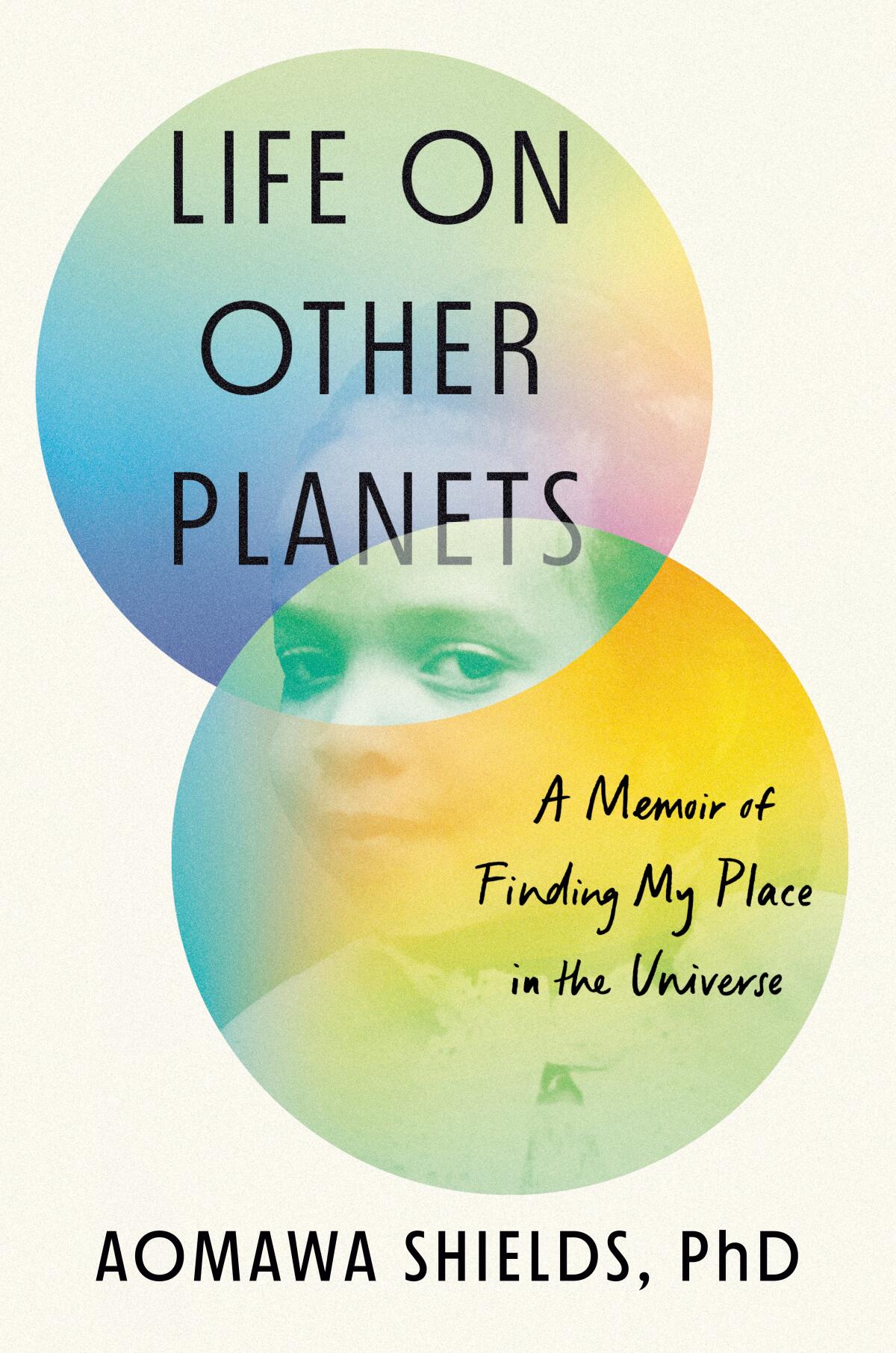

On the Shelf

Life on Other Planets: A Memoir of Finding My Place in the Universe

By Aomawa Shields

Viking: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Aomawa Shields is an astronomer and astrobiologist focusing on the climate and habitability of exoplanets. She’s also a professor at UC Irvine. She is fulfilling a dream that was, for a long time, deferred. After her first attempt at a PhD in astrophysics left her demoralized, Shields detoured from science and academia to study acting, earning an MFA from UCLA. When she returned to pursue her doctorate, she found herself the oldest student — and the only Black one.

Shields’ memoir, “Life on Other Planets,” tells the story of a Black woman fighting for her own space in a male-dominated world. Emboldened by her time as an actor, she created a path of her own, using those skills to improve communications in science (she was a 2015 TED Fellow) and outreach to children of color.

She recently spoke to the Times by video, with a telescope behind her. The interview, covering everything from media role models to the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action, has been edited for length and clarity.

Nyani Nkrumah on her first novel, “Wade in the Water,” as well as colorism, upending the white-savior story and her upbringing in the U.S. and Africa.

The book’s publicity material plays up an incident in graduate school when a white male professor suggested you didn’t belong there. But you cover that moment in one sentence and refer back to it only a few times. What role did it play for you?

I internalized that comment for many years. I felt, “He saw through me. I don’t belong in this field.” But I didn’t want to portray myself as a victim, where this one person is responsible for changing the entire course of my career.

But if that hadn’t been said, I may not have decided to go to acting school. If I’d stayed I may have stuck with galaxy formation and never found my way to studying exoplanets. His comment was negatively intended, but it was important for me to see it from different angles to forgive that person — and to forgive myself for internalizing it.

How much did everything else in your life — growing up in white communities, attending a prep school like Phillips Exeter, absorbing the messages of Hollywood — lead you to infer so much from that single comment?

There were a lot of external factors, including the media, television and movies, that fed into that feeling that I didn’t belong. Depictions of Black people have always been overwhelmingly negative, and that certainly makes a difference to young Black kids. Those messages are still everywhere.

And then there was me. I liked both science and acting, and whenever I told people back then, they’d say, “That’s so weird.” I internalized that this needs to be either/or and I need to choose.

My main message is that if there’s no role model doing what you want to do, you can be your own role model. There’s no one way to be a scientist or an artist. When I let go of the idea that it had to be either/or, then possibilities presented themselves I never could have imagined.

In 1999, when women scientists forced real change at MIT, journalist Kate Zernike broke the story. Here’s why she revisits it in her book, ‘The Exceptions.’

Can better media depictions reverse that message — help foster change in academia and the hard sciences — or is it up to those in the field to be the change?

If anything can be taken away from my book it’s: Let’s change the narrative from either/or to both/and. We need to see more depictions of women of color in leadership roles and in roles as scientists in the media and in movies. And the halls of academia need to become more inclusive.

For so long, it has been “Let’s do our best to get Black and brown students into these astronomy departments,” but what has been missing is, “How do we keep them there?” Having professors who look like them would help.

I long for a time when I’m on a plane and someone asks what I do and I say, “I’m an astrophysicist” and they don’t show this incredible surprise. I’d love it to be, “Oh, yeah, a Black woman doing that. Of course.”

You write that your tenure was offered during the protests after the murder of George Floyd, but you were relieved to see that the approval predated that. Why did it matter to you that you weren’t accepted as part of that moment of reckoning?

This is especially relevant now with the Supreme Court decision striking down affirmative action.

It’s a double-edged sword — I didn’t want anyone to think I was awarded tenure because of special consideration based on the color of my skin in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. I didn’t want that to overshadow all the work I had done. But I recognize the profound importance of policies to make sure we have equal representation in places that have been predominantly white.

Striking down affirmative action presumes everyone has an equal place at the table and unfortunately that is not the case. I’m scared of the ramifications. It’s baffling to me why affirmative action has been seen as a problem when at its core it’s about making sure everyone has an equal place. Why would people not want that?

Ibram X. Kendi joins the L.A. Times Book Club to discuss “How to Raise an Antiracist.”

Your actor training shines through in the ways you make science relatable, as well as in the nonprofit you founded, Rising Stargirls, which teaches girls about astronomy using writing, visual arts and theater. Why is that important?

My job is to build a bridge between my work and someone who may not be trained in the sciences. I don’t think I’d have been able to do that without my acting background.

When I started looking into creating Rising Stargirls, I read that using literary and role-playing techniques increases girls’ confidence so they answer and ask more questions. It allows them to process information through their own personal lenses — their backgrounds and feelings seem critical in allowing them to have ownership and retain the information.

Why did you include a list of mental health resources at the back of the book?

My first time around with science, my perception was that no one cared about how I felt, it was all about results — doing the research, taking the exam. The second time around, being in touch with who I am, I integrated what I’d learned.

Now I start every lecture and group meeting with secular mindfulness practices. That gets us all on the same page and helps students and myself to tap into how we’re feeling in that moment. I included these resources because they’re essential in identifying what it is people might want out of their lives and how to take care of themselves as they pursue it.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.