How is a Marine base like a gothic novel? Ask a Roxane Gay-anointed debut author

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Militia House

By John Milas

Holt: 272 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Few debut novelists garner the praise of author and activist Roxane Gay. But then, John Milas, whose new book, “The Militia House,” Gay calls “a beautiful horror story told masterfully and elegantly,” had the good fortune to take a seminar with her while pursuing his writing MFA at Purdue University.

Even fewer novelists go quite so big the first time out as Milas has, dreaming up a gothic novel about 21st-century Marines assigned to a forward operating base in Afghanistan. When Cpl. Alex Loyette and squad mates Vargas and Johnson sneak off base to check out an abandoned Soviet-built militia house, they have no rational explanation for what follows: visions, nightmares, lost possessions.

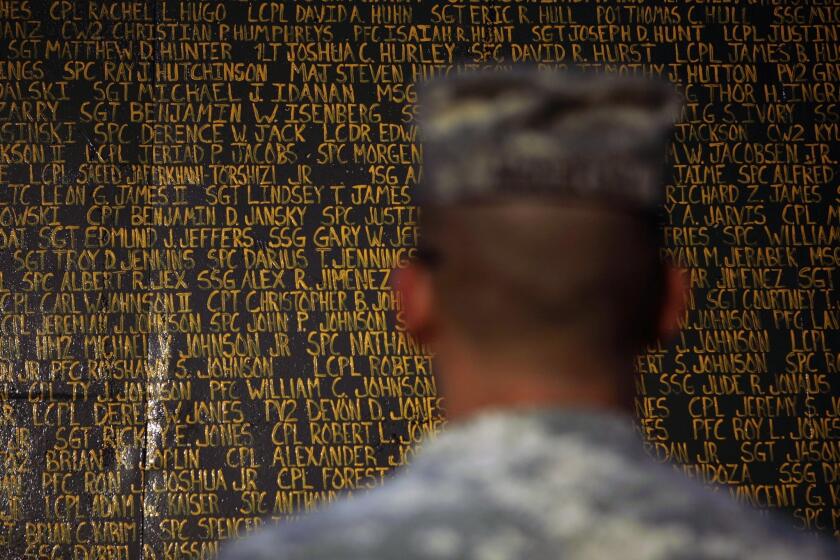

“The Militia House” employs the tropes of gothic classics (a haunted building, unexplained phenomena) to illuminate a contemporary tragedy: young service members sent overseas for long stretches of backbreaking and psyche-stressing work in support of missions and motives obscure to them.

Kevin Powers was among the best in a wave of novelists on Iraq and Afghanistan. His new thriller, “A Line in the Sand,” signals their slow fade from relevance.

Milas, who was honorably discharged from the Marines in 2012, spoke with The Times from his home in Illinois in a conversation edited for clarity and length.

“The Militia House” focuses on a squad of enlisted Marines encountering an old armory, but it’s also about the knowledge gap a soldier has to work through every day. Having spent four years as an enlisted Marine, how did you experience the division between servicemen and their superiors?

When I was stationed at Camp Lejeune, N.C., we could go to the beach — but not to the officers’ beach, even though it’s on the same coastline. You can look at the section of beach where you are not supposed to go from your own towel. You aren’t going to live in a tent with an officer. I was on a ship for a few months, and officers and enlisted eat separately. Not just different tables; a different room in a different part of the ship.

Your protagonist, Cpl. Loyette, is living under a set of circumstances in Afghanistan that almost no one here at home can imagine. How did you work to convey that for readers?

Active duty is a lifestyle. You get paid. It is not a job, though. Nothing about going to boot camp, where you don’t even see a TV, wear a watch, have your phone or get to leave, is a job. It’s preparing you for your life now until your contract is up, or you retire. You’re not reorienting yourself every day on like, “I’ll have to listen to someone today.” That’s what you signed up for, right?

There are a lot of narratives out there about combat, and there are a lot of narratives from people who were relatively high up in leadership. I always thought on seeing those books that if I had a book out it would be different from those.

When did you realize that you could write a gothic novel about a contemporary military experience?

Well, to alleviate any suspicion that I may have gone to a war to write about it, I would like to say I’ve always made art. I originally wanted to go to film school. And then I enlisted after a year of community college, and when I was on active duty, all I wanted to do was go back to college.

The Marines was not a satisfying experience overall. It pushed me back toward wanting to make art. At first, it was hard to write about the military without just ranting. No one wants to read that. It’s also not very healthy.

‘Uncertain Ground’ collects Marine and novelist Phil Klay’s essays on how we redefine citizenship and other fuzzy concepts as a nation forever at war.

What unlocked the gothic genre elements for you?

A lot of images in the novel, including a dog with its muzzle covered in huge porcupine quills, were those I really saw. They took on a surreal quality because we were busy and stressed. You’re either at work or sleeping or eating. Your sense of time gets really warped. The disconnect from the outside world, in addition to how scrambled your mind is by your schedule, was completely new. We didn’t train for this in our workups.

There is no resolution in “The Militia House.” Gothic novels are about terror. I read a conversation in which you talked about the difference between terror and horror.

It’s the Hitchcock theory of a bomb under the table that you know is there. Which isn’t horrifying. It’s terrifying. That’s not the same thing. You’re horrified when the bomb blows up after.

For Cpl. Loyette, what is the fulcrum between terror and horror?

I think the book shows what is terrifying to the characters in the sense of the war in Afghanistan and their position. Loyette knows more than his subordinates, but it’s not much. He doesn’t talk to his boss very often. There’s not much he even needs to know.

Overseas, I was always scared about what could be plausible, even if I didn’t know what was plausible. I see horror as the emotion after something happens, and for Loyette, maybe also the feeling of having to own up if something happens.

But horror is also those conversations where service members feel they are carrying the weight of the whole war. I had dinner with a friend’s parents, and they didn’t ask a single question that had to do with my experience. They were asking me the things you would ask [Gen.] Stanley McChrystal [the onetime commander of forces in Afghanistan], or about the conversion rate of Afghan currency. I mean, I never even saw Afghan money.

Here’s a summer reading suggestion you probably didn’t see coming: Try some of the excellent recent fiction produced about America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, much of it by veterans.

You convey Loyette’s interior life, so we see that the terror isn’t always about facing a known military event. It can be about something completely unexpected, something that you absolutely can’t predict.

Even when Loyette thinks he’s going to get shot he’s just on guard duty for a piece of equipment. Not even a person. Just an object. When I was overseas, I was scared and numb and tired. I think you could put a gothic spin on almost anything if you have a narrator who is unsure about what to expect from reality.

Do you plan to do more writing about the military, whether it’s about your time or not?

Some of the questions the ending raises, I’m interested in. I don’t know if I’m interested in answering them or if I’m just interested in exploring them. In terms of future writing, I’ll mention Tim O’Brien [author of “The Things They Carried”], because he got drafted into a war and has been expected to write and talk about it for the remainder of his life. It’s not like I don’t want to help other veteran writers. I just don’t want to be known for that alone.

Patrick is a freelance critic, podcaster and author of the memoir “Life B.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.