Art history — minus the men — in a zingy new revisionist compendium

Review

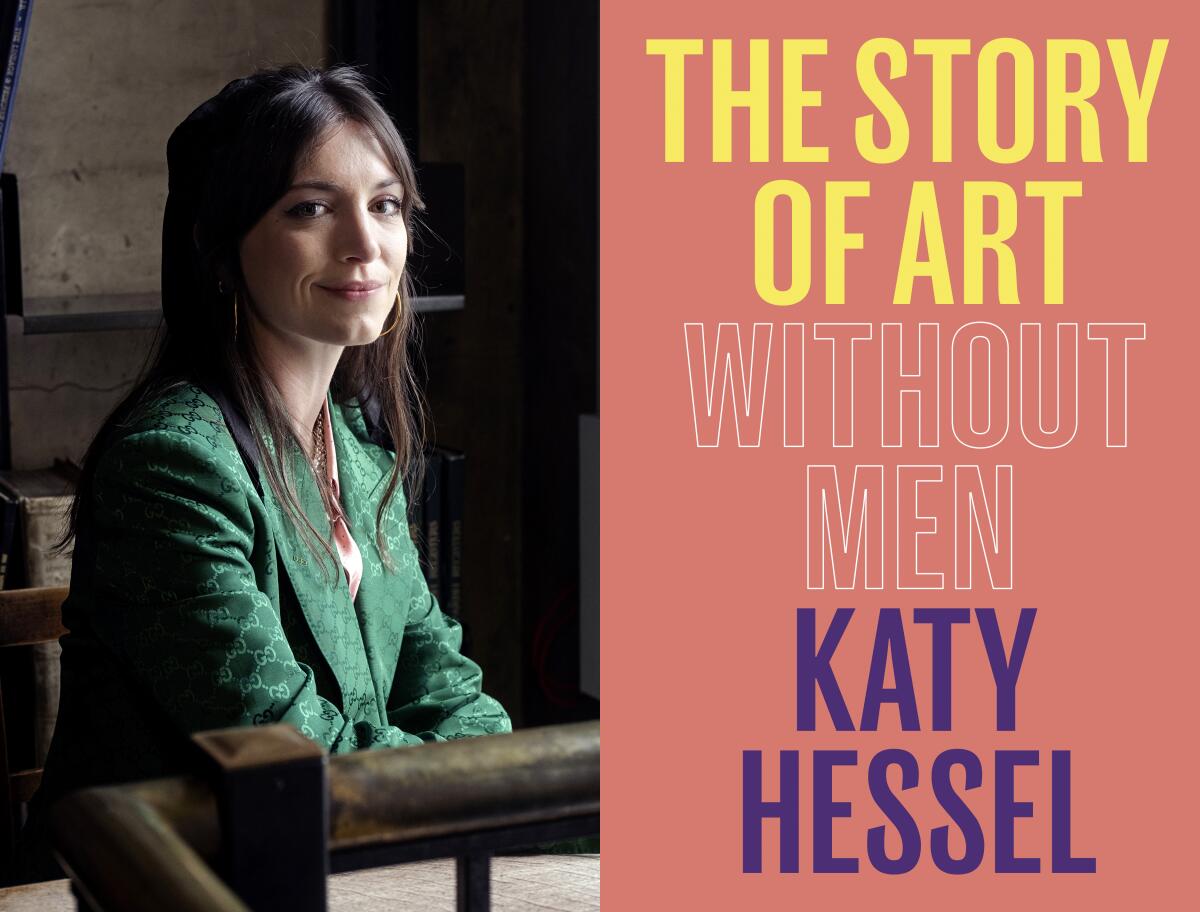

The Story of Art Without Men

By Katy Hessel

W. W. Norton: 512 pages, $45

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you haven’t encountered Katy Hessel, the feminist dynamo who’s on a mission to grant female artists their rightful place in history, now’s your moment.

A British historian and journalist, Hessel hosts a popular podcast and Instagram account, both called “The Great Women Artists.” Her new book, “The Story of Art Without Men,” consolidates her research and claps back at the “bible” of art history, E.H. Gombrich’s “The Story of Art,” whose first edition in 1950 excluded women and whose 16th (1995) had one among its 688 pages. Hessel also extends the legacy of art historian Linda Nochlin, whose legendary 1971 ARTnews essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” diagnosed the problem Hessel seeks to redress.

Hessel was spurred to action in 2015 after attending an art fair featuring thousands of artworks — all by men. A survey she conducted revealed that most young Britons couldn’t name even three women artists. And women’s paltry representation in most major museums and top-dollar international auctions is news to no one.

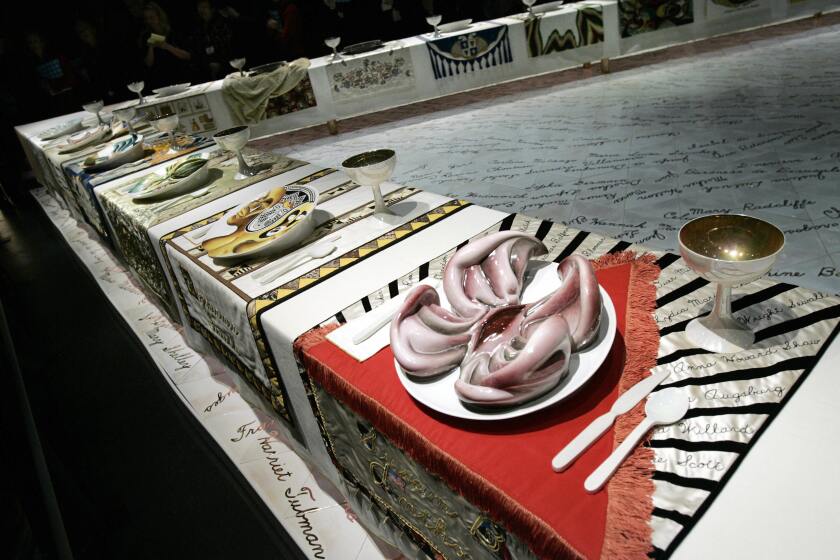

Mapping women along a loose timeline, Hessel covers huge swaths of history in lively, lucid prose, positioning these artists within (or against) dominant genres. She documents not just what they created but also the obstacles they surmounted in doing so: Barred from art academies and life drawing classes until the 1890s, they trained by copying paintings by men; used their own bodies to model biblical heroines; laced domestic scenes with subtle social commentary; masked their identities with pseudonyms; and hid self-portraits in their work so it would be properly credited — which it often wasn’t. Almost every piece Hessel references appears in a photo, most in color and some in luscious, two-page spreads.

Catherine McCormack, a course director at Sotheby’s, talks about her new book, “Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies.”

“The Story of Art Without Men” ticks off many fascinating firsts: the first female painter to run her own studio (Lavinia Fontana, who kept her birth name in marriage and raised 11 children while completing 24 commissions in the 16th century); the first fully nude self-portrait (which Florine Stettheimer painted in 1915 at age 44); the first female artist of color to enter the White House art collection (Alma Thomas, courtesy of Michelle Obama). The timing of some of these milestones alone is shocking. The first solo exhibition by a woman (Clara Peeters) at the Prado Museum, for example, was mounted in 2016.

Thrilling as it is to meet these mavericks, it’s also dispiriting to encounter so many whose careers screeched to a halt after marriage, went unacknowledged in their lifetimes and/or died in poverty, mental institutions or — in the case of the German artist Charlotte Salomon — a concentration camp. Many were rediscovered in the 1970s, and one, Carmen Herrera, had her first Whitney Museum retrospective at age 101.

Hessel’s sweeping (though Western-heavy) 500-year-history is free of both academic jargon and essentialist rhetoric, whether she’s describing the quilts of Gee’s Bend or “The Roll Call,” Lady Butler’s celebrated painting of British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War. Channeling Nochlin, she eschews the authoritarian language of “greatness,” prefacing many of her assertions with “to me….” She has an eye for the anecdotal aside. (Who knew Ruth Asawa studied with Josef Albers and served as Buckminster Fuller’s barber at Black Mountain College?) And she can be funny: Historically, she writes, “women artists had to have a powerful man (which might include God) looking after their interests.”

Claire Dederer, author of ‘Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma,’ explains why she went beyond bad men to probe our history with all artists who defy moral expectations

But in her (generally effective) effort to condense, Hessel occasionally drops key plot points. One of the great vengeance paintings of all time, Elisabetta Sirani’s 1659 “Timoclea Kills the Captain of Alexander the Great,” portrays not just Timoclea of Thebes shoving a splay-legged man headlong down a well, but a woman killing her rapist. And there is one especially regrettable error, given both the nature of this book and the catastrophic fallout of the Dobbs decision: She calls Frida Kahlo’s wrenching “Henry Ford Hospital” a depiction of Kahlo’s abortion. But it was a miscarriage; Kahlo desperately wanted the baby she depicts — floating above her naked, bleeding body, umbilical cord attached — in the Detroit hospital where she lost the child in 1932.

Even so, what Hessel achieves here is extraordinary. Thirty years ago, when I was an ARTnews writer chronicling the sexism and racism that female artists were brilliantly battling in the early Guerrilla Girls era, I would never have believed this book would be necessary in 2023. She covers a wide range of mediums (from silhouette papercutting to body art) and themes (including postcolonial narratives and queer pride). And though she keeps the focus on the women, she includes a few choice slurs by men as evidence of what these artists were — and are — up against: “Women don’t paint very well … it’s a fact,” the artist Georg Baselitz declared in 2013, echoing the critic John Ruskin, who spouted the same nonsense more than 100 years earlier.

The Getty Museum has acquired “Lucretia,” a major 1627 work by Artemisia Gentileschi, the most celebrated female painter of her time.

Today, with artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, Zanele Muholi and Simone Leigh getting the recognition they deserve from major institutions, the needle is finally moving, making the art world a vastly more interesting place. “Progress is happening,” Hessel concludes. And it will surely happen faster with the force of this spellbinding book behind it.

Mifflin is a professor at the City University of New York and the author of “Looking for Miss America.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.