A debut novel’s funny Valentine to love in all its icky absurdity

- Share via

Review

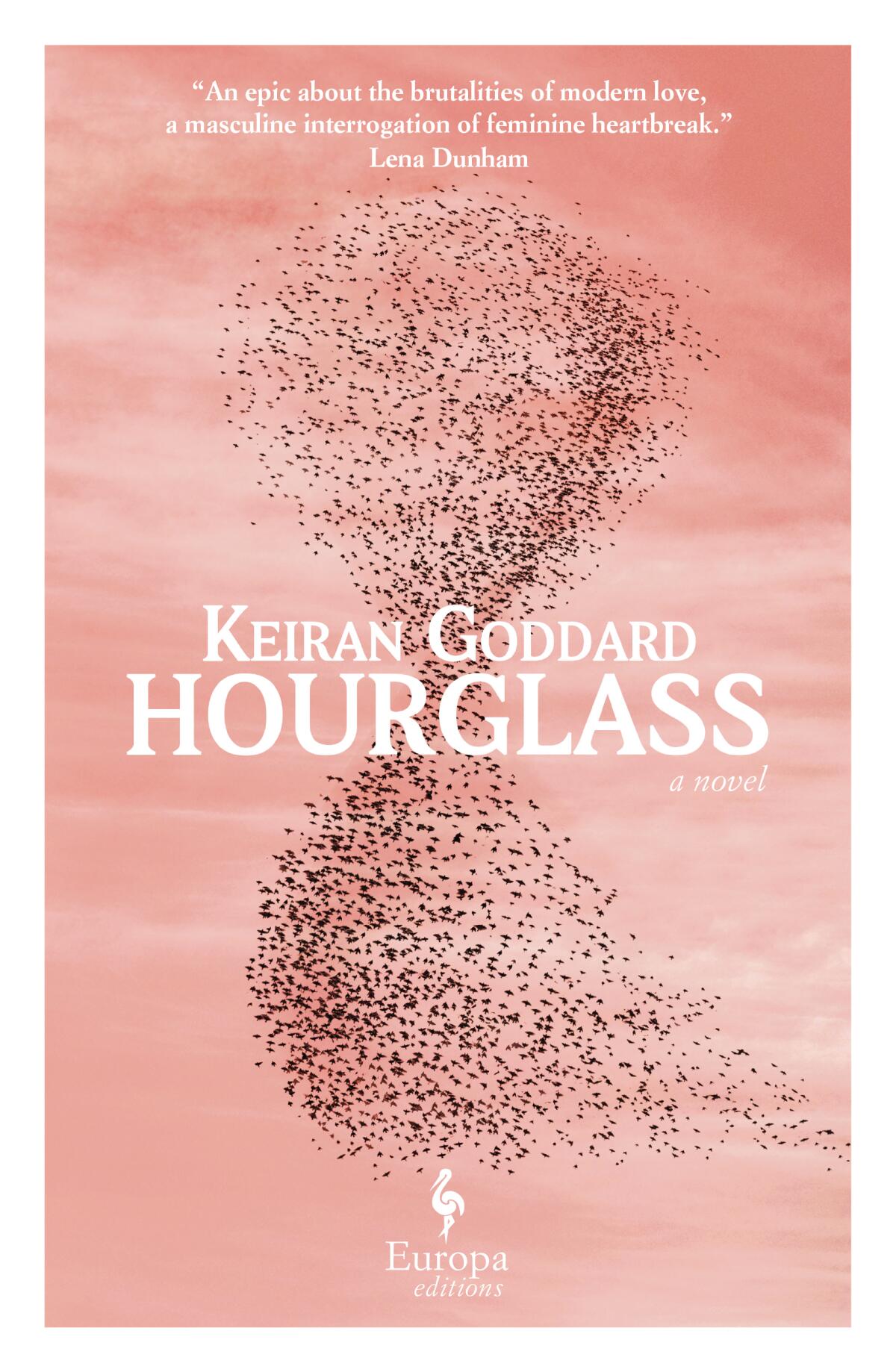

Hourglass

By Keiran Goddard

Europa: 208 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Is there anything new to say on the subject of love? No — but who cares? Romance makes fools of us all, and a love story well told invites us to bask in our shared foolishness, which is to say our shared humanity.

The best love stories prove the clichéd advice offered to aspiring writers: universal resonance springs from specificity. From “The Age of Innocence” to “The Worst Person in the World,” the tales that feel eternal are those that illuminate passion and heartbreak through characters’ idiosyncrasies. Often, the weirder they are, the better.

We can now add to this canon “Hourglass,” the debut novel by British poet Keiran Goddard. The template is a classic: Boy meets girl, boy loves girl, boy loses girl. But the delivery — a series of intimate, offbeat, often hilarious musings on a relationship, from first blush to post-breakup drinks — is a highly entertaining surprise. At first glance, the text looks like prose poetry: well-spaced, economical paragraphs of two or three lines. But the format belies the potency of the writing. This is not an airy ode; the hard truths of love and loss are boiled down here. If the novel were a sauce, it would be a reduction.

The Norwegian novelist’s latest, ‘Men in My Situation,’ has its share of male myopia but transcends when it encompasses universal conditions.

The unnamed narrator of “Hourglass,” an aspiring writer on a spartan diet of apples and bran flakes, toils at a bookstore, not hand-selling literary fiction but unloading boxes from a delivery palette late at night to the blaring sound of talk radio. He sleeps on his sofa and is always cold. Against a bleak backdrop of repetitive manual labor, it feels like “whole weeks never happened.” That is, until love arrives in the form of a fellow writer in a blue dress, and the narrator is transformed. Almost against his wishes, he catches happiness “like a disease,” becoming less lonely but also less judgmental.

“I’ve become the type of person,” he says, “who…doesn’t actually get all that annoyed when people talk about psychogeography and palimpsests when all they really mean is that they walked around for a bit.”

The relationship’s embodied pleasures and eccentricities are cataloged in intimate address to this (now ex-)girlfriend. He recalls that on their first date “you ate two small tangerines” and that while sleeping, “your legs looked like dolphins.” In the mornings, he stays in bed to watch her brush her “oil spill of slick, wet hair.” (In a perverse show of devotion, he eats a ball of it.) He asks if she will chew up potato and push it into his mouth as though he were a baby bird: “I remember that you said you didn’t mind. And I remember that you did it.”

Because it’s clear the narrator is looking back on a relationship that has ended, these small, occasionally revolting details acquire gravity. And they are only gross for not being our own; after all, these are the kinds of moments that accumulate in all romantic relationships. What do they amount to once it’s over?

The answer to that question may be a mystery. Less mysterious are the reasons behind this relationship’s end. The narrator is a challenging partner. He copes with uneasiness by drinking excessively and rattling off half-baked theories and the kinds of trivia typically collected by a 12-year-old boy, like the difference between a knife and a dagger. Lobsters never die, he tells a “ham salad of a man” at a party. “The only thing that can kill them is if they don’t have enough energy left to shed their shells!”

These frequent exclamatory asides do double duty: The punctuation suggests the raised volume necessary at the crowded parties where he frequently interjects, and the content conveys just how annoying this character probably is to those around him. (A certain meme comes to mind.) Peppered throughout are the titles of essays he has pitched to editors: “IRL and BRB No Longer Make Sense! There Is No RL So Where Would You Be RB from?” These headlines, sometimes very funny, are also exclamations, telegraphing the desperation of the socially anxious.

Nina Renata Aron’s memoir, “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls,” doubles as an ennobling history of recovering enablers of addiction.

Beneath the self-deprecating humor lurks a kind of loser bravado. Of a different partner than the one this book is about, he says, “She tells me she finds me disgusting because I sometimes (once!) drink wine from a bowl and that living with me is like living with the sad ghost of a failed comedian.”

He’s a familiar type, the kind of person who finds his propensity to disappoint others kind of amusing. It is, then, perhaps not a surprise that the story is one of love lost, bookended by periods of loneliness. During one such interlude, the narrator attempts to run a marathon, drunk, without any prior training. He vomits straight away and returns home.

“Hourglass” suffers for its sometimes mawkish language, places where Goddard reaches for earnestness but sounds insincere, or just immature. “Knowing you were coming back felt like expecting and remembering all at once,” he writes. Of the first night the narrator and his girlfriend have sex, he writes, “I remember that your skin was tight over your muscles. As if your skin was worried that your muscles were going to leave.” In a world-weary novel of blistering self-awareness and self-mockery, these are off notes.

From her wildly successful podcast, Zibby Owens has built a media empire, complete with her own publishing company and, starting Feb. 18, a Santa Monica bookstore.

Still, the charms of “Hourglass,” like those of the narrator himself, are insidious. This is a sad book that is somehow wickedly fun to read. Recollections of the materiality of love (a hand, a dress, a chair) feel timeless, but mingle artfully with offhand expressions of dread and alienation from modern life. Together, they gather a poignant weight — and remind us that in the pursuit of an antidote to loneliness, we are all sometimes pathetic.

Aron is the author of “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.