The last time American democracy stood on the brink

On the Shelf

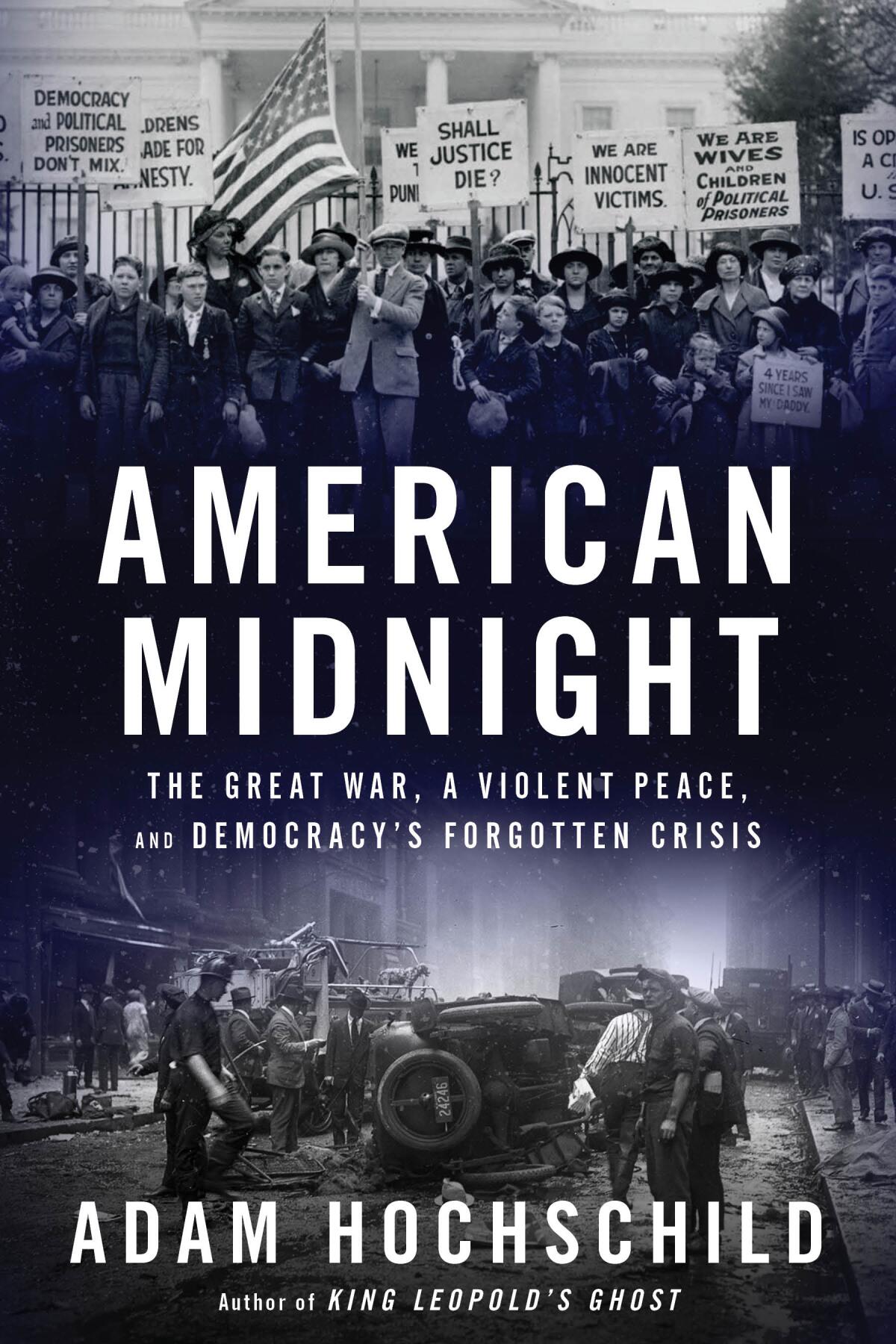

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten Crisis

By Adam Hochschild

Mariner: 432 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When historians talk about the “powder keg” set off by World War I, they’re typically focused on the unstable Balkan states that sparked the war. But to Adam Hochschild, it was right here in the U.S., whose entry into the great war set off a conflagration that severely damaged American democracy. What drove the historian to probe that dark era in his latest book, “American Midnight”? Consider that he conceived of it exactly 100 years later, in the first year of President Donald Trump.

“Never was this raw underside of our nation’s life more revealingly on display than from 1917-1921,” Hochschild writes in “American Midnight.” Woodrow Wilson, the president normally treated by historians as a proselytizer for world peace, in fact oversaw an administration that fomented widespread censorship of both speech and the press; threw political opponents in jail; failed to protect Black citizens, especially war veterans; and deported immigrants seen as rabble-rousers.

It’s a chilling tale laid out with engaging storytelling and meticulous detail, as Hochschild has done in earlier works such as “King Leopold’s Ghost,” his monumental work on Belgium’s horrific occupation of the Congo, and “Spain in Our Hearts,” about American volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

“American Midnight” closely follows several key players, including Wilson and his attorney general, as well as activist Emma Goldman and even an FBI informant who headed a local chapter of the International Workers of the World (also known as the “Wobblies”).

Hochschild spoke to The Times recently via Zoom from his home office near UC Berkeley, where he teaches journalism. Stuffed bookcases and stacks of research notes overflowed behind his desk — evidence that, at 79, he has no desire to retire after a career in which he has won a Times Book Award and a Dayton Literary Peace Prize, among other honors. He is also co-founder of Mother Jones.

We’re seeing a 100-year flood of toxic speech and attitudes.

Trump was very much on Hochschild’s mind as he embarked on “American Midnight.” “I’ve always been fascinated by this period,” Hochschild said. “And the more I thought about it, I realized that if Donald Trump had ever bothered to read any American history, it was the period he would have dreamed of. The Espionage Act would have allowed him to not just denounce his political opponents but send them to jail. It would have allowed him to censor the media he’s always railing against. There are so many echoes of the time we’re living through right now, and that we lived through during the Trump presidency, and may live through again, God help us.”

The similarities between eras run deeper than a single administration. Anti-immigrant vitriol, dismissals of “fake news,” the white backlash against Black progress, attempts to curb civil liberties, wild conspiracy theories and sharp political divisions are just some of the parallels.

Another is the rollback of liberalization that felt permanent. The decade preceding 1915 saw a “wonderful flourishing of avant-garde art, music and literature,” Hochschild said. “People were convinced that the world was changing in a good way.” The Socialist presidential nominee, Eugene V. Debs, won 6% of the 1912 vote. All that changed with the war that broke out in August of 1914.

“Forces were swirling under the surface of American life, and they can come to the surface very quickly in repressive periods,” Hochschild said. Wilson gave the impression of being a “very dignified, solemn, former college president,” someone who had written a dozen books. But the decision to enter WWI led to the “greatest repression of civil liberties in the country since the end of slavery.”

A crackdown on labor portrayed “the worker on strike as somebody impeding the war effort, and who therefore ought to be locked up,” he added. Shaken by the Russian Revolution and fearing it would spread across the ocean, politicians passed laws that made opposition to the war a punishable offense. The postmaster general was authorized to shut down newspapers deemed to threaten the war effort.

Even after the war, paranoia flourished. A series of white riots (including the 1921 Tulsa massacre) targeted Black communities. Black men in uniform were publicly beaten and lynched by white gangs. When a bomb exploded in Washington, D.C., in 1919, Atty. Gen. A. Mitchell Palmer ordered the rounding up of anyone known to be a member of certain political groups. Thousands were jailed, and hundreds of immigrants were deported.

Scott Ellsworth talks about ‘The Ground Breaking,’ a new follow-up to “Death in a Promised Land,” his pioneering 1982 exposé of atrocities in Tulsa.

Wilson, the heralded peacemaker, signed off on these domestic measures. I asked Hochschild whether Wilson embraced authoritarianism or was too distracted by the war to pay attention.

“He advocated openly for things like censorship of the press,” the author replied. “But he didn’t seem to pay attention to what it actually meant in practice.” After Wilson’s journalist friends protested, the president “would send a note to the postmaster general … and the postmaster, who served as the chief censor, would reply that they were violating the Espionage Act. Wilson would back off.”

While historians have written of the period known as the Great Red Scare, it hasn’t garnered as much attention as Sen. Joe McCarthy’s 1950s blacklists, even though the repression it inspired was more brutal. Hochschild’s parents, whom he describes as “liberal but not radical,” had friends who fell victim to McCarthyism. “One of my first political memories is of my parents angry at the TV set as they watched the [House Un-American Activities Committee] hearings.”

Hochschild soon developed his own political convictions. He went to college to become a novelist but turned to journalism after he became involved in civil rights struggles in 1960s U.S. and South Africa. He spent the summer of 1962 “working for an anti-apartheid newspaper in South Africa, which was an absolutely life-changing experience.” He and his now-wife, noted sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild, went to Mississippi in 1964.

Our time of protests and war has often been compared to the 1960s; Hochschild disagrees. “I remember the ‘60s as a time of hope,” he said. The election of Ronald Reagan began a retrenchment, he adds, exacerbated in later decades by the inequalities of gerrymandering and the electoral college. These trends — and the radical turn of the Supreme Court — concern him most.

Does all of this make Hochschild pessimistic? Not at all. “Compared to a hundred years ago, there’s a much better established sense of the importance of civil liberties, of free speech, [as well as] the freedom to organize labor unions.” He also said he believes the press, despite obvious exceptions, is more robust.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

“There are many things worth celebrating about this country — and parts of American culture,” he said. Some of this came into relief for him while living in other countries. He doesn’t even think nationalism is all bad. “I think there’s a positive side of nationalism where you can be proud of the culture you live in, that you build, that do not involve denigrating other cultures.”

Never mind his fervor in sounding the alarm about dark American undercurrents; what keeps retirement at bay is Hochschild’s idealism. “I don’t feel my ideals have changed in a basic way at all,” he said. “I would like to see a world where the good things of life are distributed far more equally than they are today. And I’m attracted to [writing] about times and places in history where other people have had similar ideals.”

Which means Hochschild has enough work to cover several lifetimes.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.