Review: The author of a literary classic, Helen DeWitt tries a novella on for size

- Share via

On the Shelf

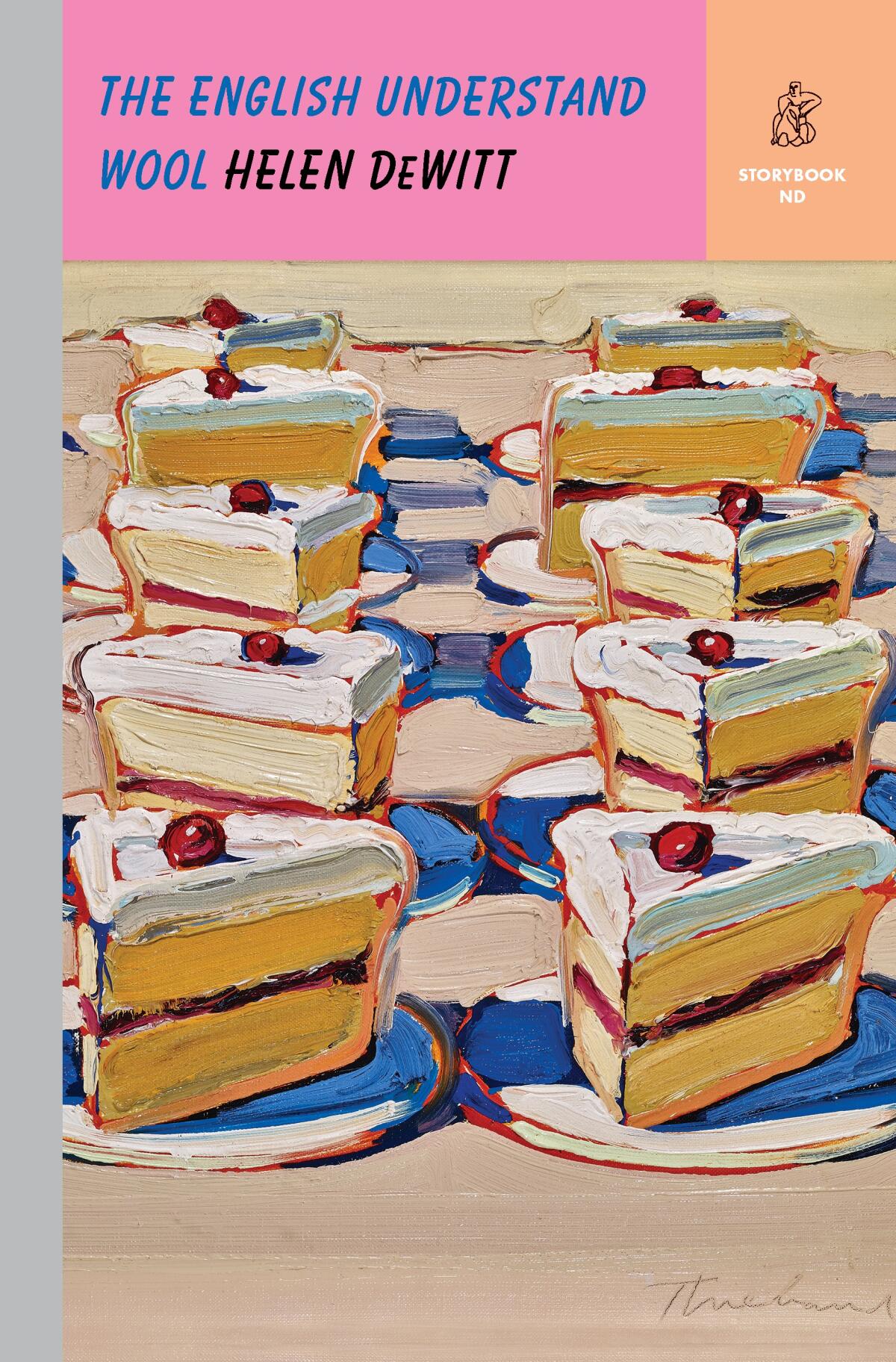

'The English Understand Wool'

By Helen DeWitt

New Directions: 64 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

New Directions is publishing Helen DeWitt’s new novella, “The English Understand Wool,” as part of a series called “Storybook ND,” promising “the pleasure one felt as a child reading a marvelous book from cover to cover in an afternoon.” Other authors featured in this series of highbrow pocket books include Clarice Lispector, César Aira and László Krasznahorkai, but even on these 60-odd pages alone, the experiment would be a success.

The arrival of a new book by DeWitt, even one in short pants, is cause enough for celebration. They’re one-of-a-kind, as funny-haha as they are funny-peculiar. And, as she demonstrated with her 2018 short-story collection, “Some Trick,” she’s just as brilliant on smaller canvases.

It seems unkind to spoil the sleight-of-hand pleasures of “The English Understand Wool,” but in brief: Marguerite, a 17-year-old raised in Marrakech and tutored in the ways of high culture and haute couture by a wealthy French mother and distant English father, finds herself abandoned one day at an expensive London hotel. Into her suite, instead of Maman, comes a detective bearing surprising news. Overnight, she becomes a person of international interest, and when she’s offered $2.2 million for the rights to a book about her life, she must figure out how to survive in a treacherous world of editors, agents and lawyers.

“It was quite clear that any ‘biopic’ would inevitably be in mauvais ton,” Marguerite observes, dismissing the idea of her life as a movie with one of her pet phrases (from the French: bad taste; vulgar; ill-bred). “But a book, a text, this is something one can control.”

Or so she thinks.

The #PublishingPaidMe campaign on Twitter revealed disparities. Where do we go from here?

DeWitt, who has seen the sharp end of publishing, knows otherwise. She’s had much to say about the industry — little of it nice — since her first novel, “The Last Samurai” (2000), was painfully delivered to the world. Though feted at the Frankfurt Book Fair, its publication was hampered by typesetting challenges, accounting errors and legal frustrations. Despairing, DeWitt twice attempted suicide. And while the finished book was well reviewed and has attracted an evangelical fan base, it was long out of print and only reissued in 2016 after a career-suppressing interval. Only one more novel has emerged — the sexual-harassment comedy “Lightning Rods” (2011). “The literary world does quite like the notion of genius,” DeWitt once wrote, “but it has no place for a Picasso.”

With this in mind, it’s tempting to read “Wool” as straight-up satire, focusing as it does on an ingenious but eccentric writer pitched against a philistine publisher. Marguerite’s editor, Bethany, bemused by her focus on Maman’s notions about textiles and the family’s Ramadan travel plans, hopes to coax from her a more sensational account of her childhood, inserting editorial suggestions such as: “If you don’t talk about your feelings there is nothing to engage the reader and keep them turning the pages.” Marguerite, however, sticks to her guns.

In fact, “Wool” is as much a terrific character study as it is a satire, with Marguerite’s quirks driving both plot and comedy. What she sees that Bethany doesn’t is that there are many roads to the truth. Her version of events, however idiosyncratic, is the only way she can explain herself; to tell the story any other way would be “in mauvais ton.” The English may understand wool, as Maman says, but that doesn’t mean they know what to do with velvet or satin. So it is with the material of our heroine’s life: There’s a right way to fashion it, even if at first it seems abstruse.

‘The Palace Papers’ follows editor and author Tina Brown’s ‘Diana Chronicles’ with a tumultuous new chapter — and more admonitions than revelations.

Marguerite, like many of DeWitt’s characters, operates by her own peculiar logic, and much of the humor derives from seeing it teased out to the nth degree. Here she is dismissing Bethany’s objections to the bottle of Puligny-Montrachet she — a teenager — has managed to order over lunch in a Manhattan restaurant:

“If you tell me this is illegal, well, we are in the realm of speculation. Maybe they respect someone who respects good wine. Maybe they’re tired of people who come and order the cheapest thing on the list, or order whatever they happen to sell by the glass.” Five more withering contingencies follow before she concludes, with cool condescension, “Surely this is not what you wanted to discuss.”

In this respect, Marguerite recalls the great mother-son tag team of “The Last Samurai,” relentlessly subjecting everyday situations to their withering (if absurd) logical scrutiny. Six-year-old Ludo, trying to convince his mother he doesn’t need to go to school: “Let’s take two people about to undergo 10 years of horrible excruciating boredom at school, A dies at the age of 6 from falling out a window and B dies at the age of 6 + n where n is a number less than 10, I think we would all agree that B’s life was not improved by the additional n years.” The self-assured mind trapped in a world it perceives as irrational and moronic is perhaps DeWitt’s great subject.

“The English Understand Wool” is a perfect introduction to the anarchic pleasures of DeWitt’s fiction. Once again, using the obtuse ratiocination of her characters, DeWitt aims at nothing less than expanding readerly consciousness, gesturing toward a world of untapped possibility freed from convention. Why go to school if you’re not going to learn anything? If the law is stupid, flout it! Don’t let the bastards get you down!

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

DeWitt’s inspired skepticism about the ways of the world stems, one suspects, from her love of languages, as reflected in Marguerite’s insistence on writing in French where only French will do. “If you were immersed in other languages,” DeWitt has written, “the arbitrariness of your own linguistic world would become visible — the authority of its conventions would no longer be uncontested.” As with language, so with thought: Step outside of orthodoxy, free the mind. For that insight alone, keeping up with Helen DeWitt remains an essential, invigorating and wickedly pleasurable way to spend your time.

Arrowsmith is based in New York and writes about books, films and music.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.