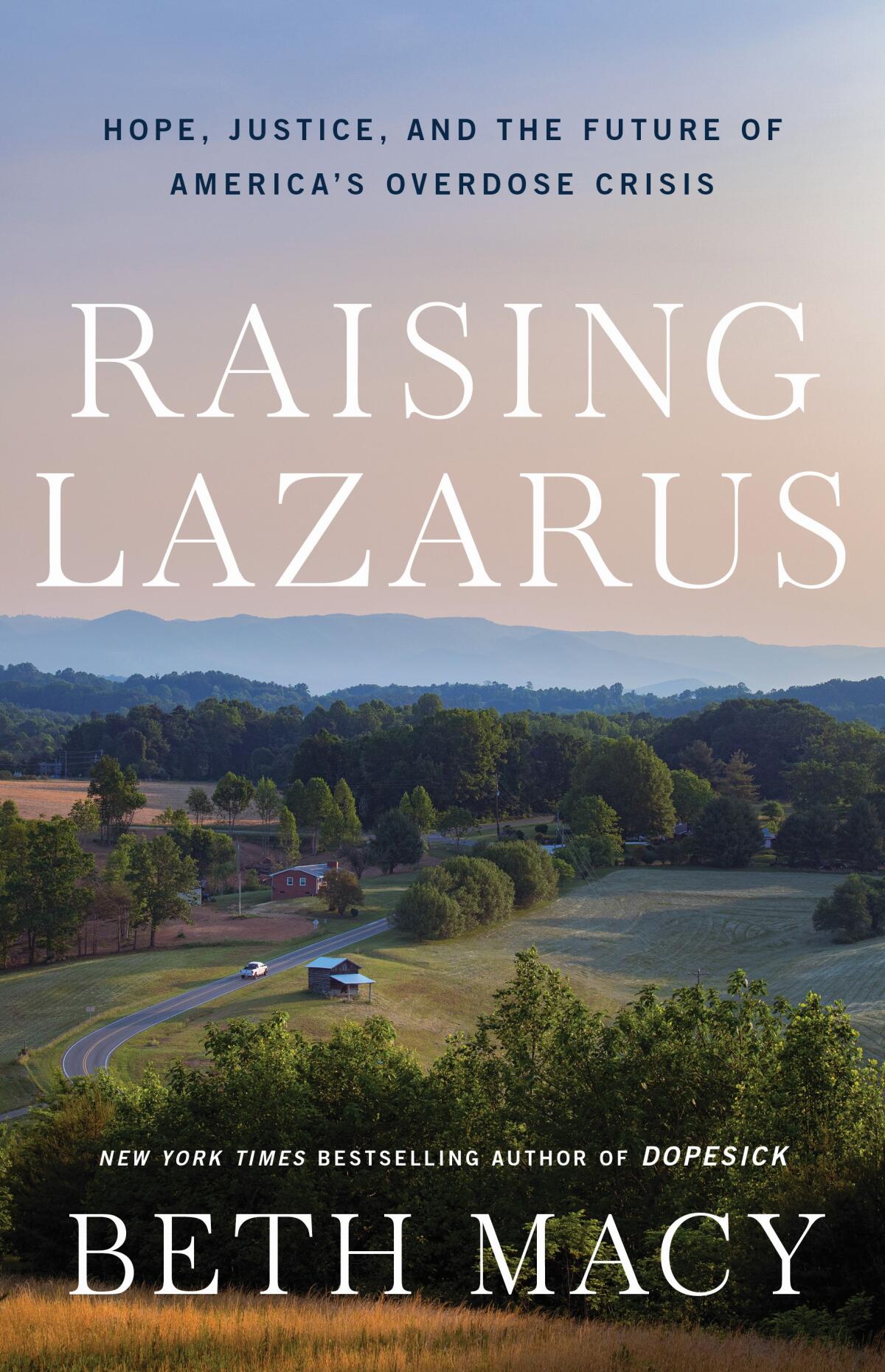

‘Where the soul meets the bone’: Why ‘Dopesick’s’ Beth Macy stays on the opioid beat

- Share via

On the Shelf

Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America's Overdose Crisis

By Beth Macy

Little, Brown: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When Beth Macy finished her 2018 book, “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America,” she was done with the subject.

“There was no way I could do another book on opioids. I felt emotionally battered. I was so depressed and didn’t see any hope,” Macy says by video from her home in Virginia shortly before the publication of, yes, her new book on opioids, “Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America’s Overdose Crisis.”

Macy couldn’t shake the crisis in part because it has never let up, but also because she approaches her work with a journalistic passion that can cross over into advocacy. Driven by corporate greed, piled on top of bureaucratic mismanagement and indifference, the opioid epidemic has ruined millions of lives via addiction, death and the trauma of families ripped apart — and that number grows daily.

Macy was neither the first nor the last to tackle the subject. Barry Meier’s book “Pain Killer” started the conversation in 2003, and Sam Quinones contributed “Dreamland” in 2015. “Dopesick” was followed by Ryan Hampton’s “American Fix” and Patrick Radden Keefe’s bestseller “Empire of Pain.”

Nor is Macy alone in pursuing the beat beyond her first book. Between follow-ups and screen adaptations, all these journalists are still involved in a subject that’s become wrapped up in their identities, pushing the story forward in hopes of one day ending the crisis.

Capturing both corporate corruption and on-the-ground tragedy has been especially hard on Macy, who in her years of reporting on life in Appalachia has prided herself on getting up close and personal with the people she’s covering. When she worked on a previous book, “Factory Man,” she recalls, an editor told her that he’d never had a journalist get so close to their subjects. “He said it in a chiding way,” she notes. “I thought, ‘Dude, how do you think I get this material?’”

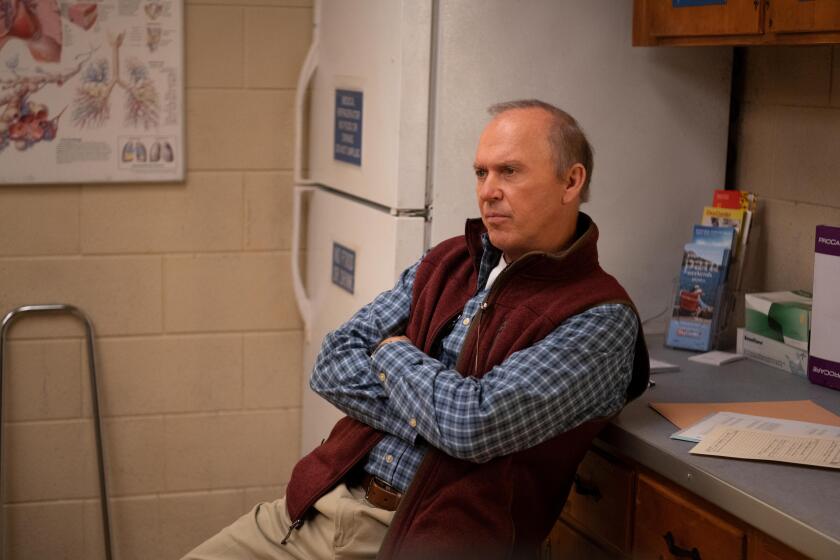

A ‘Spotlight’ for the opioid crisis, starring Michael Keaton as a small-town doctor ensnared in the epidemic, ‘Dopesick’ is schematic but effective.

Macy cites Walt Harrington, author of “Intimate Journalism,” as saying, “You’re not getting close enough unless you’re right on the line, struggling with it every day.” She drove one “Dopesick” subject to her Narcotics Anonymous meetings, interviewing her along the way, although she took her husband’s advice and declined to fetch that same woman from a trap house (she called someone else to help). “I’m always right on that line,” Macy says.

Macy re-immersed herself in “Dopesick” as a writer and executive producer for the Hulu adaptation that starred Michael Keaton and that recently earned 14 Emmy nominations.

“A couple hundred thousand people bought my book and I’m grateful to each and every one, but 10 million people watched the Hulu show,” Macy says. “Not everyone reads books or the New Yorker. The show reached the ordinary person. People in Appalachia went nuts for it.”

Macy pushed to ensure that the series emphasized the importance of methadone and buprenorphine (also called “bupe”) in treatment, which “Empire of Pain’s” Keefe says was crucial to moving it beyond just a condemnation of the Sackler family, owners of Oxycontin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, and those who enabled them.

“The episodes about medication-assisted treatment are hugely important, given the reach a TV show has,” Keefe says. “That gave people the vocabulary with which to start that conversation.”

Macy’s new book comes on the heels of Quinones’ drug-epidemic follow-up, “The Least of Us,” and will soon be followed a Netflix limited series, “Painkiller,” based on the work of Meier and Keefe.

As these journalists beat on against the current of an epidemic made still deadlier by fentanyl, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic turmoil, Keefe believes each new project has something to offer. “There’s nobody whose life hasn’t been affected in some way,” he says, adding that each person has found a different part of this massive story to tell. “It takes a village with people figuring out a way to tell different details in a compelling fashion.”

Macy was pulled back in in 2019, when she started hearing small bits of good news. “They were outliers, but there were people finding ways to bring treatment to the most marginalized people, and I thought, ‘This is a story I could have the heart to tell,’” she says.

Sam Quinones, author of ‘The Least of Us,’ a followup to his prophetic addiction chronicle ‘Dreamland,’ talks about meth, homelessness and defiant hope.

In the book, Macy also tracks activists like photographer Nan Goldin as they pressure the courts and government to make the Sackler family pay for its behavior instead of hiding behind Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy. The author is less optimistic on that front: “They’ve been vilified, but they still have their wealth, and wealth equals power.”

Traveling alongside those seeking to disrupt the patterns of addiction, Macy gravitated toward controversial approaches. “I got to witness cutting-edge medical care in a McDonald’s parking lot next to a dumpster that smells like soured French fries,” she says. “I was really in that place where the soul meets the bone, and I was seeing things no one else was seeing, and now I get to tell other people. I feel energized right now, not like I did after ‘Dopesick.’”

Macy’s book differs from both memoirs of people in recovery and traditional journalistic approaches. She follows individuals doing yeoman’s work but also watches reluctant government officials and conservative communities fight change — particularly on anything that deviates from a cold-turkey approach ill-suited to severe opioid addiction.

“A very small percentage of Americans really understand that abstinence-only thinking is wrong where opioids are concerned,” Macy says. “It’s sad that some of the hardest-hit places, especially in the South, are the most resistant.”

Keefe, the author of the acclaimed nonfiction books ‘Say Nothing’ and ‘Empire of Pain,’ talks about his new collection of gripping pieces, ‘Rogues.’

With payments starting to flow, as the result of lawsuit settlements, from pharmaceutical companies into state governments to aid with the epidemic, Macy hopes her book will “be a guidebook for people in power to see what they can do with the money.” (She also has speaking engagements lined up in the South with various government officials and judicial groups.)

“Start with the low-hanging fruit,” she says. Although major changes like “Medicare for all” would have a huge impact, important first steps could include expanding drop-in clinics for medication-assisted treatment. “There are maybe 20 of those across the nation, and every community should have one. The main thing is to make the treatments easier to access than the dope.”

As Vancouver, Canada, is dispensing fentanyl and New York City has set up the nation’s first “safe consumption sites,” Macy knows many rural places may not even feel politically ready for needle exchanges or methadone and buprenorphine treatment in jails.

“Raising Lazarus” offers even more incremental starter ideas, such as fielding community surveys to build a clearer picture of public opinion and share it with risk-averse public officials.

Macy believes her advocacy is an extension of the work she and her peers have already done in books and onscreen. All are striving in different ways to reduce the stigma around addiction, make it easier for people with addictions to get help and place the weight of the blame where they believe it belongs — on the corporations that were effectively the first drug dealers of the crisis.

“What we really need is to keep getting little bits of change,” Macy says. “I’m hoping to give communities that are struggling glimmers of light and practical tips so they can change hearts and minds.”

OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reached a settlement over its role in the nation’s deadly opioid crisis that includes U.S. states and local governments.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.