Why Lidia Yuknavitch aims to ‘unwrite an Americanness’ with a new novel about America

In Lidia Yuknavitch’s novel “Thrust,” a myriad of species across different points in time conceive an ocean of characters. The multiple points of view, ranging from a girl named Laisvė who can time-travel to laborers and immigrants who worked on assembling the Statue of Liberty, stems from Yuknavitch’s curiosity “in what is possible with the polyphonic voice,” she says, “Because I am deeply uninterested in and dismayed by the universal subject that follows a singular hero’s journey that mimics or reflects the patriarchal order.”

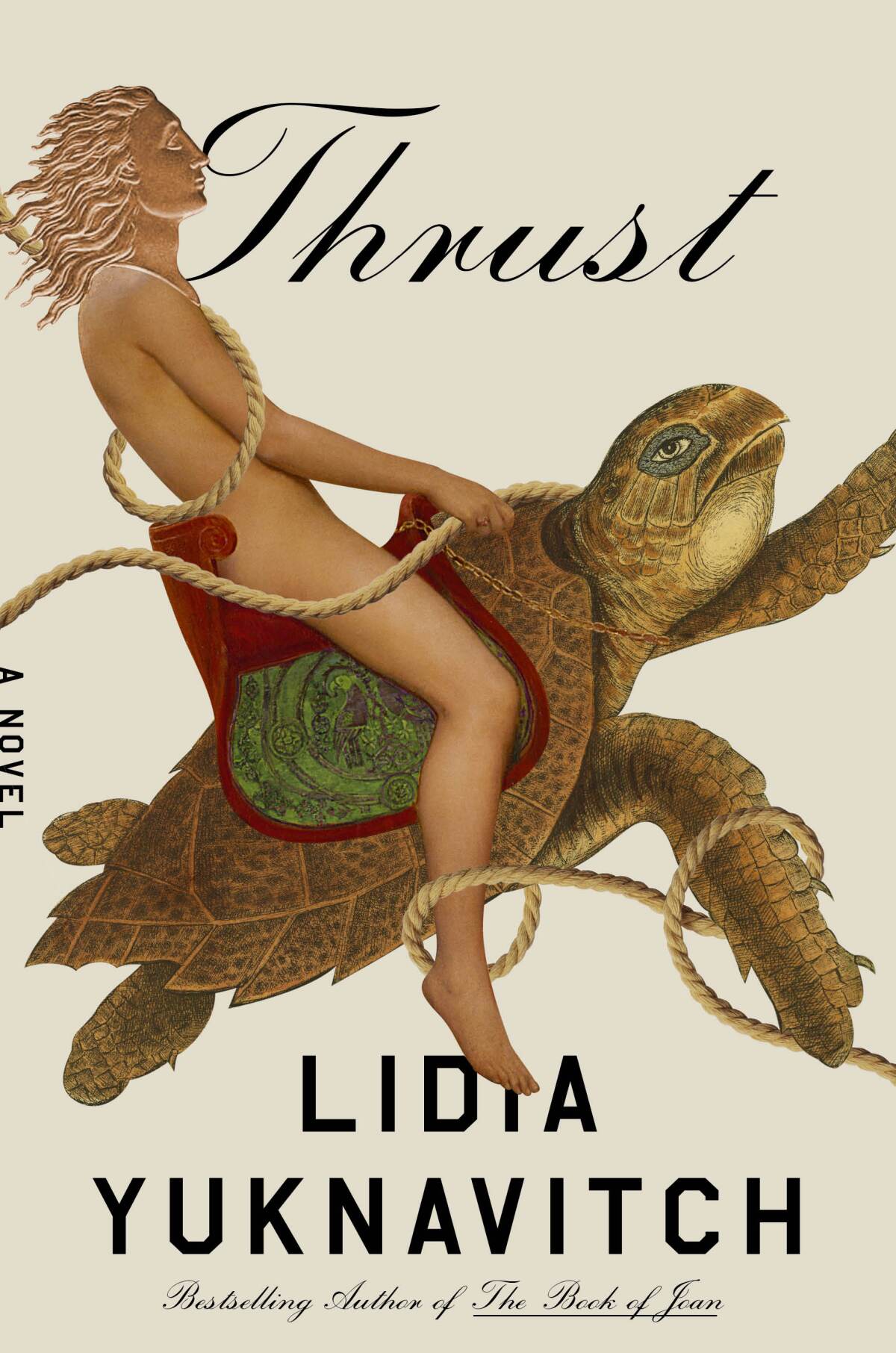

Out on June 28, it’s a book that uses history and America as a jumping-off point to dissolve borders and boundaries, as Laisvė journeys from the wrecks of a city overrun by a police state in the near future, using objects as a way to carry her across two centuries and conversing with animals along the way. “Whether I am succeeding or not, I’m actually trying to unwrite an Americanness,” Yuknavitch says. “And I’m trying to write toward a set of global possibilities, where nations fall away, and national definitions turn back into sediments.” In a chapter that deals with the injustices of child labor, for instance, Yuknavitch writes about “the sunk cost of mechanizing America, creating the fiction of freedom, including the slashing of woman and child bodies.” “Thrust” unveils the illusions that America was built on and continues to perpetrate, and how those beliefs can lead to bodily harm.

The Portland, Ore., author of six other books, including “The Book of Joan” (a reimagining of Joan of Arc) and the lyrical memoir “The Chronology of Water” is known for corporeal writing, a method she teaches that is “writing by and through the body.” “Thrust” is the culmination of everything she has been writing toward, a blistering excoriation of power structures that also honors the resilience of those who fight back. I recently spoke with her about the book’s origins, the slipperiness of language, and why she doesn’t believe in linear time.

While reading this novel, I was struck by how much research you wove throughout, from facts about canning to linguistics. What was the first spark for this book?

I may have missed my calling to be some kind of researcher or librarian where you sit in a room and treat all of human history as an archaeological dig, because I love research. But when I say research, I mean I’m going in there with a creative mind and heart. So I don’t have an allegiance to facts, I have an allegiance to the imagination. The idea for the book definitely came from the conditions of our present tense. And it also came from ideas about children and young adults. And ideas about climate change. And the predicaments we find ourselves in that feel so dire. They’re not in the future, it’s not something to be afraid of in the future, it’s already happened. What needs to shift? What has happened over time and space that echoes each other? What is liberty anymore, if it ever existed? If you loosen history up into particles, anything can be part of the story.

All of your books form their own kind of universe centered around recurring themes, including bodies and water and storytelling. Aurora, one of the characters in “Thrust,” says “I bring stories to life, so that we might recover our own bodies. I am wholly narrative, I am the hole of narrative, I am the holy narrative.” What is it about repetition that speaks to you, as a writer?

I love and delight in the relationship between words. And so when one word hints at, or echoes, or carries the trace of another word, I’ll follow it. So that’s one way to talk about it, is just semiotics. The relationship between words interests me or even obsesses me. But another way to talk about it would be to say, I can’t write a poem to save my life. But I think I have a poet’s heart, and a poet’s desire to be inside language, in its rhythms and sounds. And so I think I’m often trying to create a poetics of prose. I’m trying to make waves and circles and patterns and rhythms.

The third thing to say would be I think of language like I think of the ocean. Language, kind of like the imagination, isn’t ordered. It’s ordered by humans. So language as a sign system could be thought of as free-floating and wavelike and filled with all the symbols and words and ideas. But then we bring grammar and syntax and diction and meaning making and connotation and denotation, we take the ocean of sign system and make it into sentences and words, meanings. But I still believe they could be shaken back up and rearranged.

Freedom is at the heart of this novel, and with that, captivity. Immigrants and children being forced into labor, as well as the violence that is inflicted on humans by other humans, not just through physical means but even through the loss of language or the rigidity of language. If language can confine us, how can it also free us?

The thing about language is that one could rearrange it at any moment. And so a concrete example is Gertrude Stein. She was showing us something about the fluidity of language. And she was showing us something too, which is a central theme of “Thrust.” Is it possible to loosen our grip on binary organization in language, like male, female? And it may mean words getting set free and made more fluid again, and changing how we speak to each other and how we describe experience.

Words, like patriotism, have become befouled. We’re in a particularly fraught time where words and meanings are sliding all around. That’s a crisis space, but it’s also a possibility space. If we could get rid of the terms “man” and “woman” as biologically essential, and a binary that divides humans, other stories of who we are could emerge.

So much of “Thrust” has to do with breaking up artificial or forced borders or labels that have been placed around space, time and history. It’s a book that is both timeless and very much of this moment too — existing in a liminal space. What is it about the threshold that compels you to dwell there?

Well, I don’t believe in linear time. I’m willing in whatever’s left of my life to imagine time as something different than the definition I have inherited. And so in the book, one question I gave myself was, how are time periods in dialogue with one another? How do they echo each other? How do they crash into each other? How do they resist each other? How do meanings change across time and space?

Can you talk about the different meanings behind the title?

So there’s the Statue of Liberty, her arm. That’s a version of a kind of thrust. And it’s not phallic. It’s not a penis. Then there’s a sexual connotation that we ordinarily or have in the past associated with maleness or men, which is the crass thrusting motion of phallocentrism. And I wanted to give that back to the hips of women and queer people and non-gender binary people as a means of pushing desire out in unending ways into the world and each other. It’s about, you know, the hips of a woman giving birth or the hips of two queer women coming together so differently than heterosexual intercourse, or desire and empowerment and imagination, never stopping, always thrusting forward or backwards or anywhere. The imagination thrusts forth in children. The symbolic thrusts I tried to see in this novel are about relational energies transferring between people and releasing and calming and releasing in waves.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.