Punk saved Sasha LaPointe’s life. Her memoir on her Native roots helped her heal

On the Shelf

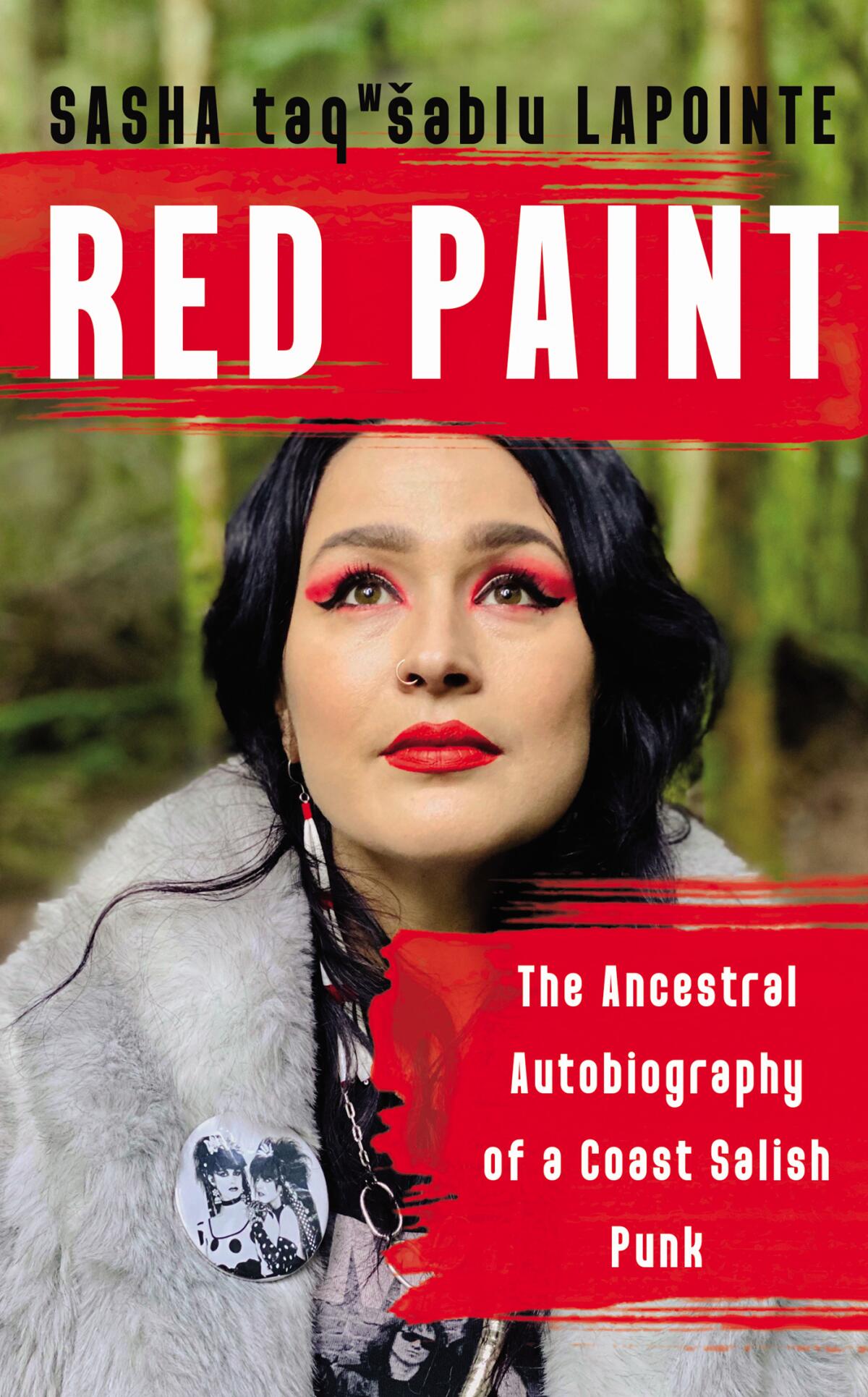

Red Paint: The Ancestral Autobiography of a Coast Salish Punk

By Sasha LaPointe

Counterpoint: 240 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Sasha LaPointe is a Coast Salish woman who grew up on a reservation north of Seattle. As a tween, she discovered punk; the feelings expressed by powerful punk groups like Bikini Kill resonated with her own. As a teenager, she ran away frequently and found her own community among the artists of Seattle. But something was still missing; her new memoir helped her find it.

“Red Paint” weaves together the story of LaPointe coming of age and coming apart with that of her ancestors, especially the women. One of them, Comptia, was the sole survivor of her family after smallpox was introduced by white settlers.

Retracing Comptia’s steps leads LaPointe, now 38, to harrowing discoveries about her family — and herself. Her legacy as a Coast Salish became a tool on her way to recovery; she was sexually assaulted as a child by a trusted adult and then later by a companion. She gestures toward those memories with lyricism, avoiding re-creating the trauma. In grad school, she writes, “I had excavated the bones of these memories, unaware that they would reanimate, that they would chase me into my dreams.” She was diagnosed then with PTSD.

LaPointe has been a member of the punk band Medusa Stare and is currently headlining a new project, Fleur du Louve. Also a poet and an essayist, she spoke with The Times via Zoom, in a conversation that has been edited for clarity and length.

Had it been 25 years? Twenty-three? No, wait — 22. Right?

What is it about punk that lines up with who you are?

I felt very isolated. I remember looking through magazines like Rolling Stone and Sassy, seeing all this cool stuff that looks nothing like my experience out in the middle of the woods. We had a little boom box and I would take it into the bathroom and be the moody little tween listening to the college radio station. I have this very, very vivid memory of hearing a Bikini Kill song for the first time. I had never heard a song about sexual assault before that was so angry and powerful and charged. And it really impacted me. All of a sudden, I felt not alone.

I very much wanted that. I remember going to Bellingham [Wash.] and Seattle and seeing these DIY bands and spoken word and performance art, and that sort of opened the gateway for me. That started way back when I was 13.

Even though western Washington is your ancestral home, your book conveys the sense of discombobulation that I often see immigrants describing.

As a Coast Salish person, these places are my ancestral home. But it’s like existing in the aftermath of settler colonial trauma. I’m deeply connected to these places, but there is this sense of loss. Growing up on Swinomish — it’s truly breathtaking. It’s beautiful. I think about it when I look back on my childhood, and it was like a paradise to me, but then I think that it’s also strange knowing that I come from a lineage that was literally taken.

Do you find that you have in any way recovered that sense of connection?

I think it’s in process, but it’s getting better. I have this home in Tacoma and I’m around the corner from my parents, which is amazing, because I hadn’t lived in close proximity to my parents in a very long time. My mom and I walk our dogs together, and in those moments, I have this massive gratitude [for] walking with my mom in the woods as she’s literally harvesting medicine [from plants]. In those moments, that connection is there, that safety is there.

There’s been a lot of discussion in recent years about trauma narratives. To tell the truth in the book, you have to recount some of the traumas, but there’s always the worry that it’s some kind of weird entertainment for the reader.

It’s something I feel really strongly about. Early on, even when the writing was in baby stages, I wrote about trauma in my body [in a way] that’s very lyrical and dreamlike. I had a professor who kept saying, “You need to show us what happens.” That felt gratuitous and exploitative. Because of my background, it’s hard for me to stand up and say, “I’m not going to do that.”

I’m going to write this in on my terms. I’m not a Lifetime series. I’m not going to show trauma as entertainment. And this is the art that I’m wrestling onto the page.

The new comedy, set on an Oklahoma reservation, uses its rich, highly specific sense of place to offer a refreshing take on contemporary teen life.

White people sometimes seem to treat Native culture as if it weren’t lots of different tribes and nations. And the appropriation can feel kitschy: turquoise and dream catchers and Pendleton blankets. This is not your responsibility to figure out, but do you have any inkling of where this impulse comes from?

That’s a layered and loaded question. When I see the Coachella girls with their big dream catcher tattoo or their Indian princess tattoo, I think it comes from the idea that we, as Native people, are gone. We’re like an antique you can find at the vintage shop and think, “That’s cute.”

They want the Hollywood buckskin Native. It’s like we’re frozen in time as Native people because we lost. I think that’s slowly changing. I have friends who work on [the TV series] “Reservation Dogs,” and these representations of contemporary Natives will eventually shift that. That’s why I love to see these narratives that are saying, “Hi. We’re still here.”

One of the moments where I knew I wanted to tell my story was while I was on tour with Medusa Stare. We were in Chicago playing a punk venue. Outside the show, my bandmates were in the van, and there were these two white women smoking and talking, up in arms because there was this girl [me] walking around with “war paint” on her face. They said they were going to tell the club owner our band shouldn’t play because I was being culturally inappropriate. My bandmate burst out of the van and told this woman it was a Native woman she was talking about, and if you want to know why she’s wearing paint, you could ask her, although it’s none of your business. They didn’t even know what a Coast Salish woman looks like.

This book is for those ladies.

You write, “Call me a girl who loves Nick Cave, and night swimming, and ramen, and old Bikini Kill records … Call me anything other than survivor.” What do you mean by that?

People tell you you’re so brave, so resilient, but they expect you to be broken. I think about other people who don’t come from generational trauma and how they never have to worry about being brave. I remember having this moment, standing in front of Comptia’s house [in Ilwaco, Wash.]. I was weeping, and I got really angry at all those who say I’m so brave for telling my story. It was this longing to be anything other than brave.

Memoirist Melissa Febos attacks the gender dynamics of the anti-personal-essay crowd in “Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative.”

In your music, what part of you are you expressing? The vulnerable part? The angry part?

I think that is an amazing question because we just played a show a few nights ago. We had this new song I was really excited about called “Tulips.” It’s about growing up on the Swinomish reservation and how angry we got because of the Tulip Festival. When the settlers showed up, they made dikes and changed the waterways where ancestors gathered shellfish. There was this rich abundance there, and then settlers showed up and they were like, “We’re changing this. And every year we’re going to throw it in your face and do this big tulip festival.”

We ended our set with “Tulips,” and I was jumping around and just yelling. I wasn’t worried about how I was sounding. It was just anger, but in a very good way, a really healthy way. In my writing, there are tender moments where it’s very vulnerable and raw and honest. And there’s a place for that. But in my music, I get to celebrate my rage as an indigenous person.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.