How ‘Parent Trap’s’ Hayley Mills survived kid stardom, bulimia and losing her Disney money

On the Shelf

Forever Young: A Memoir

By Hayley Mills

Grand Central: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Hayley Mills always knew Walt Disney played a formative role in her life. After all, the studio founder was the one to cast the then-unknown Brit in 1960’s “Pollyanna,” offering her a seven-picture deal that would make her one of the most famous child stars in the world.

But it wasn’t until she found herself inside the Disney archives five years ago that Mills realized just how profoundly her identity had been shaped by him. In 2016, during a visit to the Burbank lot, the actor was invited to explore three boxes that contained hidden treasure — previously unseen correspondence between Mills, her parents and Walt himself.

The Disney she saw reflected in the notes did not exactly resemble the genial father figure who’d once toured her around his theme park and gifted her a gold charm bracelet. He did not want her in any “heavy dramas or sex involvements” as a teenager — the starring role in Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita” was quickly shot down — and refused to let Mills’ parents “run the show.”

Back in London, Mills told her two sons about what she’d unearthed on the lot. For years, she’d mulled the idea of writing a memoir about her unique childhood. Now, her kids insisted she try again: “You really must do it, mum, before you forget your name.”

“I didn’t even know if I was capable of it,” Mills recalls. “But my eldest son, Crispian, said he would help me come up with a proper plan. And that made all the difference in the world, because I realized I wasn’t going to be alone.”

Even at 75, Mills is continuing to come to terms with how her girlhood reverberates — hence the title of her book, “Forever Young,” which comes out next Tuesday. In the memoir, she writes of “sleepwalking” through her early career, only now taking her “first real chance to understand and take ownership of the strange and remarkable things that happened to me.”

Mills focuses on her long struggle to shed the saccharine “Pollyanna” image, calling to mind recent Disney stars like Miley Cyrus and Demi Lovato who rebelled against the squeaky-clean Mouse House. And yet despite a bout with bulimia and a battle to keep her childhood wages, Mills somehow remains unembittered — an outlook she credits, in part, to “Pollyanna.”

Demi Lovato’s rebirth

In her home office, Mills sits peacefully surrounded by the ghosts of her past — acting trophies, framed photographs, a handwritten note affixed to the wall. It’s early evening in her home near the Thames River when she appears on a video screen, the same blond heart-shaped bangs curving around her temples that she wore as a girl.

“I ought to get a big Japanese screen and put it behind me so people can’t see,” she says with a laugh. “I’m not really a hoarder, but it’s difficult to get rid of things that one has associations with.”

Her hoarding tendencies aided her in writing the memoir, however, as she called upon the stacks of journals she began keeping at age 12. Then her son, Crispian — a screenwriter who’s worked with Simon Pegg, helped to tease out his mother’s stories; he also gave her a stack of index cards and told her to begin jotting her memories on them. Together, they arranged the finished cards on the floor and Mills set off to write on her own.

The initial pages were enough to interest Gretchen Young, vice president of Grand Central Publishing.

“She wasn’t holding back,” recalls Young, who went on to acquire and edit Mills’ book. “She faced a ton of challenges while maintaining this youthful public image that the adults around her were invested in. To me, that had echoes of today’s young child stars.”

Mills was born into a showbiz family. Her father, John Mills, was a well-known actor who’d starred in “Great Expectations” and her mother, Mary Hayley Bell, was a playwright. One day, when she was 12, Hayley was bouncing around the house singing TV jingles while her father was meeting with a director. The filmmaker was so taken with the girl’s charisma that he decided to cast her as the lead in his next project, “Tiger Bay.” Watching that performance, a Disney producer thought she might be right for a remake of a 1920 children’s classic.

The “American Beauty” star discusses her memoir, “The Great Peace,” and the abuse and shame she endured while seeming “too special to have problems.”

“Pollyanna” is the story of an orphan, first played by Mary Pickford, who is taken in by her wealthy, cold aunt. Despite her circumstances, the pigtailed protagonist maintains an upbeat attitude — optimism that’s tested when she falls from a tree and suffers possibly permanent paralysis.

The reboot was a massive hit and turned Mills into a household name.

“Walt described her to me as ‘the best talent to come into the picture industry in the past 25 years,’” wrote gossip columnist Hedda Hopper in a 1960 Times column. “Even then I wasn’t prepared for John Mills’ amazing little girl.”

Mills won an honorary Oscar for the role, becoming the last of a dozen kid actors to receive the Academy Juvenile Award; other recipients include Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland.

After she played a pair of long-lost twin sisters in “The Parent Trap” the following year, Mills’ popularity skyrocketed. At one point, she says, more than 7,000 pieces of fan mail a week were sent to her at Disney. One letter included a diamond ring; another offered to send an otter to live in her bathtub.

But back home in the United Kingdom, her life remained basically the same. Sure, everything seemed rather glamorous on her trips to Hollywood, when she was put up in the Beverly Hills Hotel. At boarding school, though, they were still feeling the aftereffects of wartime austerity; students weren’t allowed to leave the table until they’d eaten all of the food on their plates.

From the outset, Mills’ career was tied to her father’s. Disney promised her dad a major role in “The Swiss Family Robinson” if she accepted the terms of its contract. (10,000 pounds for “Pollyanna” — or about $235,000 in 2020 — with a 10,000 pound increase each year. No residuals.)

“I knew Daddy was proud of me, but he never spoke of it,” Mills writes in the book. “By glossing over things that were real and important, like being awarded an Oscar, they were unwittingly denying milestones in my life. … I was left with the overwhelming conviction that somehow my lucky break had been a mistake — and I started to feel guilty about my success.”

Compounding the drama, Mills lost the statue — which was half the size of a grown-up Oscar — decades later. After working on a three-month-long job in America, she returned home to find it had either been misplaced or stolen. When she asked the academy for a replacement, she was rebuffed.

“After they gave me my little statuette, they stopped doing them,” she explains. “From then on, when children like Tatum O’Neal won, she got a good, ol’ big-sized Oscar. They broke the mold of [my] Oscar.”

It’s been more difficult to shake the reputation that came along with the role for which she won it. Mills speaks with both immense gratitude and mild frustration about “Pollyanna.”

“It did seem to kind of slow my development into being an adult,” she acknowledges. “Actors are so much braver today. You look at Daniel Radcliffe from ‘Harry Potter,’ how brave he’s been with his career. He’s really gone out on a limb, and I admire that so much.”

Everyone is ignoring Daniel Radcliffe.

As a girl, Mills says, she was more preoccupied with pleasing the adults around her — terrified of disappointing all of the grown-ups who didn’t want her to grow up. So she began vomiting after every meal, developing bulimia in a bid to stay little and childlike. In 1964, Hopper, the same Times columnist who had written about “Pollyanna,” noted Mills’ shrunken figure: “Hayley Mills, 18, Thinner and looking like the million stashed away for her,” read the headline.

“Seven pounds thinner than when I last saw her, her 112 pounds are distributed in the correct places,” wrote Hopper. “‘I’m trying to shrink my stomach to peanut size,’ [Mills] said.”

The actor was terrified of following in the footsteps of peers like Garland. Once, while sharing a bill with “The Wizard of Oz” legend at a “Night of 100 Stars” taping, she listened as fellow performers gossiped about how Garland had just emerged from the hospital following a suicide attempt. Standing in the wings, Mills says she watched in shock as John Lennon yelled: “Show us your wrists, Judy!”

The comment wasn’t meant to be cruel, Mills surmises in her memoir: “His own life’s experiences had left deep fissures of anger in him and I’m sure he recognized another’s pain.”

Nevertheless, Mills felt a kinship with Garland. “I could relate to those same feelings of powerlessness, of being a studio ‘asset,’ and the intangible pressure and expectation a child feels,” she writes. “Judy’s was a cautionary tale and I started to worry that unless I broke out of my own little straitjacket, I could end up in a similar place.”

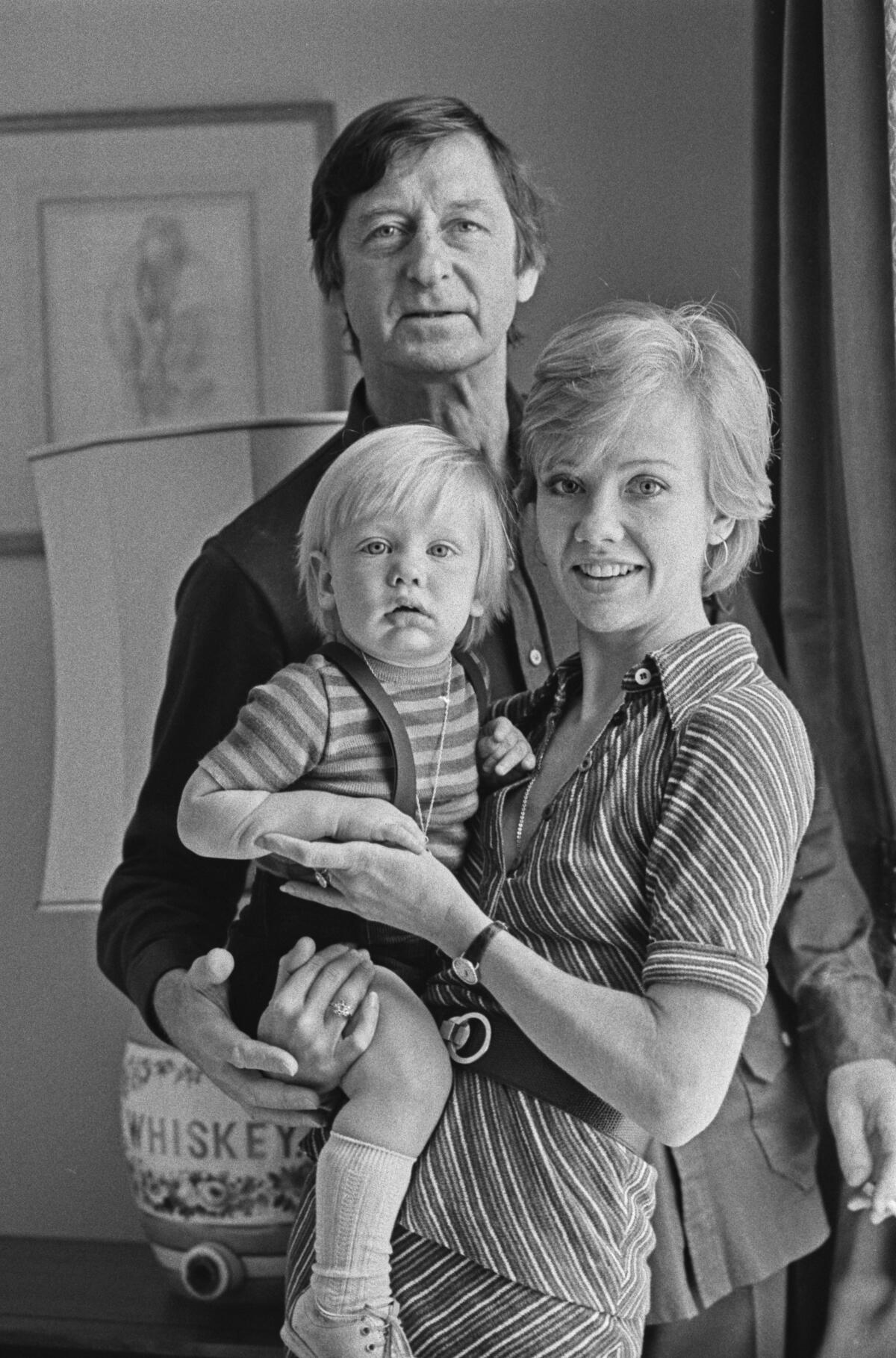

The solution was to escape Disney. When she turned 20, her contract expired and she opted not to renew it. The following year, she fell in love with Roy Boulting, one of her directors on 1966’s “The Family Way” — a movie that also featured her first nude scene. The filmmaker was 53 years old, and the couple’s age difference disturbed both loyal fans and her parents, though that did not stop her from marrying Boulting in 1971.

“They could have handled it differently,” Mills says now, reflecting on her family’s reaction to the unconventional romance. “And how were they to know that this wasn’t the love of my life? I was so absolutely adamant, and I kept reminding them of the example of Oona Chaplin, who married Charlie Chaplin when she was even younger and there was an even larger age difference.”

Mills and Boulting had one child together — Crispian — before divorcing in 1977. The split occurred just a couple of years after a devastating ruling from Her Majesty’s High Court of Justice.

When she turned 21, Mills was finally given access to a trust that had been set up to house her childhood wages. But there was barely anything left in the account. Her savings had been subjected to a 91% tax rate set up by the Inland Revenue to build England back up after the war. She pleaded her case to the British government for years, but her appeal was shot down for good in 1975. If she’d won, she says she would have been able to keep roughly 2 million pounds — well over $17 million today.

“I never saw it,” Mills says, clearly now resigned to the situation. “I knew it was there and one day I would have it, but it was just sort of a dream, and then one day the dream was gone. Occasionally, I think: It would have been nice if I had the freedom to say no.”

Renée Zellweger is making her way through a bowl of potato chips in the lobby of Casa del Mar, the beachfront Santa Monica hotel she used as an office for a couple of years while she was developing a television series, “Cinnamon Girl,” about four young women coming of age in Los Angeles in the late ’60s.

After she became a mother, Mills did some stage work and then took a handful of television gigs in the U.S. — like playing the beloved teacher Miss Bliss on “Saved by the Bell.” It wasn’t until Crispian helped his mother put together “Forever Young” that he realized how badly his mother had been “robbed.”

“The way she describes the experience of having all that money taken away is very innocent — like, how can you feel sad for something you never had,” Crispian says. “And I think people will now realize that there is an element of Pollyanna in her that is very real. That was truth coming across on screen.”

True to that spirit, Mills insists that even the discovery of those salty Walt Disney letters hasn’t colored her view of the man to whom she owes her career.

“He was a father figure, and fathers do that — say, ‘No, you can’t go to this dance. You can’t go on a motorbike with that boy,’” she says. “That’s life. I was extremely fortunate to be under contract to a studio like that. To a man like that. I was not exploited in the way that we understand that word.”

Mills still acts occasionally, most recently shooting a few episodes on an Acorn TV drama called “Pitching In.” She says she’s really only looking for character parts that don’t require her to “worry about what I look like at 6 in the morning.” She’s primarily interested in spending time with her five grandchildren — to whom her book is dedicated — especially because working to make up for her lost wages took so much time away from her own kids.

“The more I wrote this book, the more I realized I was talking about everybody’s struggle to grow up,” says Mills. “I think there was a bit of Pollyanna in me to start off with, actually. I do tend to look on the bright side of life.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.