D.H. Lawrence hated women writers. Now they get to speak

On the Shelf

Burning Man: The Trials of D.H. Lawrence

By Frances Wilson

FSG: 512 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

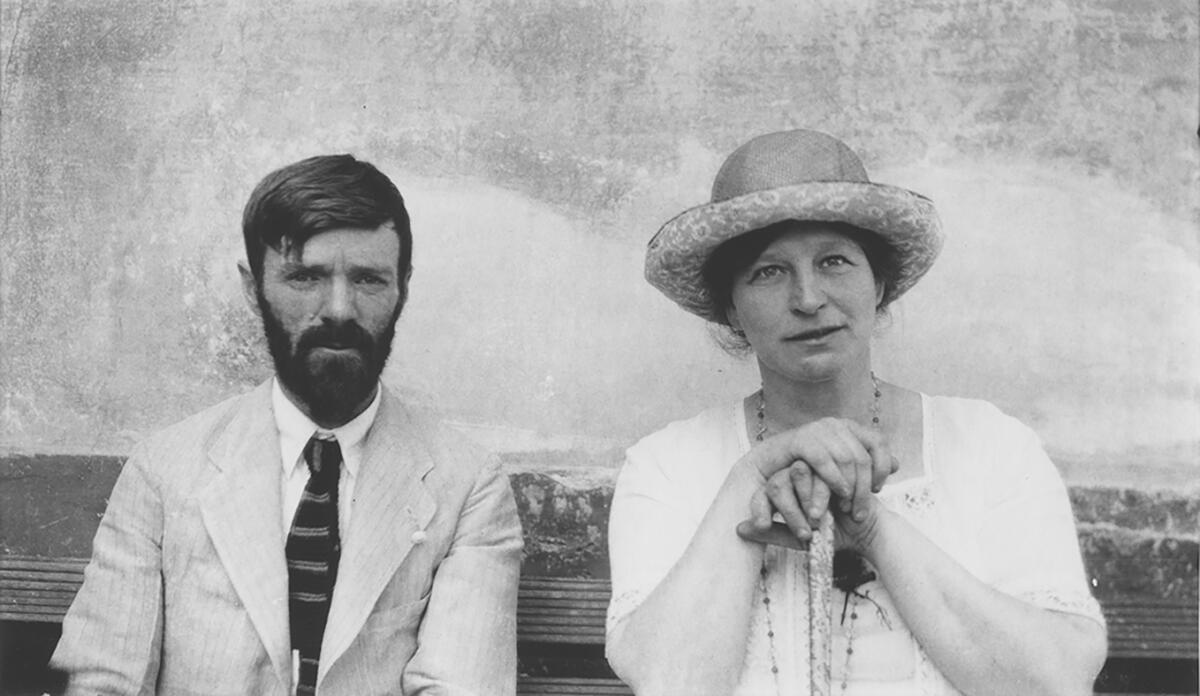

There was a time I would rather have endured minor surgery than read a 400-page biography of D.H. Lawrence, whose misogyny is canon. “The one vile man I have ever known,” wrote Virginia Woolf. When Hilda Doolittle, once a Lawrence acolyte, became pregnant by another man, Lawrence told her, “I hope to never see you again.” Most horribly, when his erstwhile friend Katherine Mansfield lay dying from tuberculosis (which she had most likely contracted from him), Lawrence wrote in his last letter to her, “I loathe you. You revolt me, stewing in your consumption.”

Yet for all his loathsome qualities, the novelist has remained a source of interest and inspiration for writers. When his widow Frieda’s memoir appeared in 1932, just two years after his death, there were already 16 books about Lawrence on the market. Though the pile of Lawrenceana has since grown to monumental proportions, Frances Wilson’s new book, “Burning Man: The Trials of D.H. Lawrence,” is a revelation, proof that a great biography has little to do with the greatness of its subject.

“Burning Man” follows close on the heels of Rachel Cusk’s latest novel, “Second Place,” inspired by another Lawrence study, “Lorenzo in Taos,” written by Mabel Dodge Luhan in 1932. Luhan, a self-proclaimed keeper of artists and a character of epic proportions, plays a big part in “Burning Man” as well. Believing she had the power to get artists to do her bidding, she called Lawrence to Taos, N.M., in hopes that he would capture the spirit of the place. He believed he would finally complete an American novel. Instead, it was all-out war. Lawrence came to the conclusion that Mabel, the domineering American woman, was the root of all evil. Mabel, for her part, believed that in Lawrence she had “seen the Devil.”

“Second Place,” Rachel Cusk’s first novel after the radical, brilliant “Outline” trilogy, follows a forceful woman who’s had enough of difficult men.

In both “Lorenzo in Taos” and “Second Place,” the female narrator is humiliated by the male artist, made to wear form-fitting clothes and scrub the kitchen floors at his demand. Any artistic impulse on the part of the women is quashed. “I am not going to think of you as a writer. I’m not going to think of you even as a knower,” Lawrence told Mabel. “You know and write whatever you feel like, of course. But the essential you, for me, doesn’t know and could never write.” Cusk’s fictionalized Lawrence (he is called “L” and the action moved to England) laughs at the books the narrator has written.

In “Burning Man,” Wilson discusses what Lawrence called his two selves, split between “the person” and “the artist.” Writing to his girlfriend Jessie Chambers, Lawrence explained: “There was a second me, a hard, cruel if need be, me that is the writer which troubles the pleasanter me, the human who belongs to you. This second me belongs to nobody, not even to myself.”

Writers and their inspirations are a perennial topic of news and gossip, especially today, when “autofiction” is the rage. Recently there was an essay by a young woman who discovered with horror that the author of a “viral” New Yorker short story, “Cat Person,” mined elements of her life to create a portrait of a disturbing sexual encounter that resonated with many readers.

Wilson describes Lawrence’s novels as “exercises in auto fiction, which genre he pioneered, in order to get around the restrictions of the genre. ‘Art for my sake,’ he quipped, but he was being entirely serious.” Contemporary writers like Karl Ove Knausgaard, Ben Lerner and indeed Cusk are lumped in under this term for a fictionalized form of autobiography. Novelists have always written from life, though this fact has not lessened some readers’ shock and dismay at the process.

Cusk has been vilified for mining her life in any genre. “When writing about her own life, Cusk often sounds depressed, and appears not so much selfish as self-involved,” wrote the reviewer of Cusk’s memoir, “Afterlife,” in the New York Times Book Review. “Maybe it’s an obvious point to make about a 45-year-old serial memoirist, but she finds herself disproportionately fascinating.” When this review was published, three volumes of Knausgaard’s extremely self-fascinated magnum opus, “My Struggle,” had been published to great acclaim.

Novelist Lynn Steger Strong on the revolutionary passivity of Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh and Sally Rooney — how we’ve misread them and what comes next.

While the use of personal details by Lawrence and Knausgaard is accepted in service of their art, when a woman writes, her work is deeply suspect: distasteful, narcissistic, even dangerous. When Mabel Dodge Luhan and the “Second Place” narrator dare to write in the wake of male genius, they are met with unrelenting hatred. “It was my suspicion that a woman’s madness represents the final refuge of the male secret,” Cusk’s narrator writes, “the place where he would destroy her rather than be revealed.”

Just what is that “male secret”? Wilson makes the case that much of Lawrence’s energetic vitriol toward women comes from his forbidden desire for “male friendship.” One of the most compelling parts of “Burning Man” is Wilson’s appreciation for Lawrence’s out-of-print memoir of his friend Maurice Magnus. Lawrence believed it was his best writing too. “Which means,” Wilson explains, “that D.H. Lawrence’s best single piece of writing is an unclassifiable document virtually unknown to the majority of his readers.”

Wilson also reveals that Lawrence was an early reader of E.M. Forster’s “Maurice,” whose gay romance (only published in 1971) he lifted and transformed into a straight courtship in his novel “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” As Mabel, the nonwriter of “Lorenzo in Taos,” writes, “Do we dare call his conception of his rôle on earth pure fantasy, a poetic avoidance of the real problem, which lay, really, within himself? I wonder.”

As a man who wrote his friends, lovers and enemies into his fiction, sometimes in hateful ways, Lawrence comes to be defined by the struggle between these two selves. Wilson puts it in a chilling way: “The effeminate adolescent ... had evolved into a young man whose poise was cool, hypnotic and threatening. The transformation in Lawrence was down to one thing: he had turned from a human being into a writer.” That threat — the writer’s threat — is at the core of “Second Place,” only in this case the cool, hypnotic threat is female.

“In the Land of the Cyclops” is the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s first essay collection in English, a refreshing shift from his epic, “My Struggle.”

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.