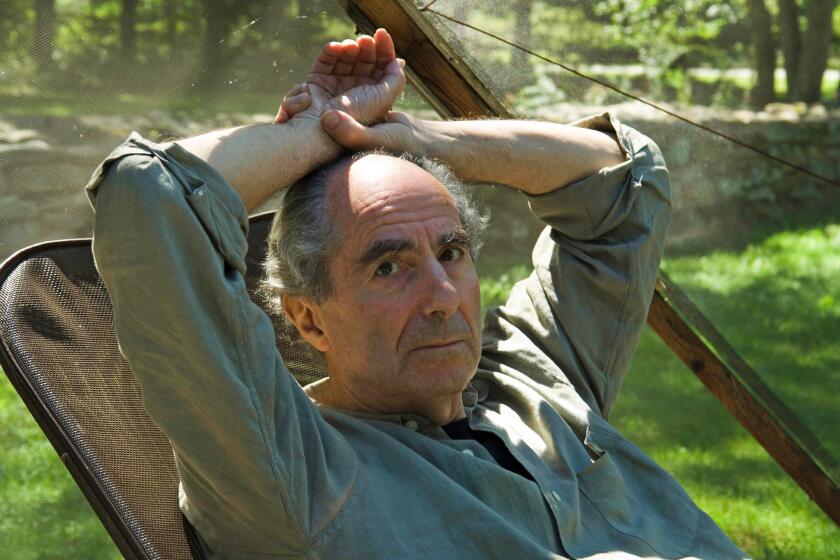

‘That was harsh’: Philip Roth’s biographer defends his book and his subject

On the Shelf

Philip Roth: The Biography

By Blake Bailey

W.W. Norton: 912 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When literary biographer Blake Bailey met with author Philip Roth in 2012 he was asked, “Why should a gentile from Oklahoma write the biography of Philip Roth?” Bailey responded, “I’m not a bisexual alcoholic with an ancient Puritan lineage but I still managed to write a biography of John Cheever.” “Cheever: A Life” was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and won the 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography. Bailey’s other volumes charted the lives of 20th century lions Richard Yates and Charles Jackson.

For the record:

2:06 p.m. March 31, 2021An earlier version of this article misquoted Bailey twice, first by omitting quotation marks around “bitch of a wife” — those were Roth’s words — and second by stating “actual lie” instead of “actual life,” in reference to Cheever.

Next week, three years after Roth’s death, comes “Philip Roth: The Biography,” weighing in at a comprehensive 900 pages. Bailey examines the author’s two bitter marriages and the circumstances surrounding the creation of his most memorable works, from his 1959 National Book Award-winning story collection, “Goodbye, Columbus,” his breakthrough at the age of 26, to his death of heart failure in 2018.

“I was a huge fan of his writing. But it was my fourth literary biography,” says Bailey. “I didn’t have enormous human expectations for writers of the first rank.” The author’s death came just in time to skirt the #MeToo movement, which likely would have scorched him for his casual sexism and prodigious philandering — sometimes with his students while teaching at prestigious institutions.

Regardless, Roth was one of the last century’s most vital literary voices; he captured the American identity as it was, in contrast to the country’s idealized self-image. Bailey’s biography balances Roth’s personal flaws and enormous gifts. It is the portrait of a lech, a mensch and a virtuoso.

Roth was concerned about his public profile and in the 1990s began work on a biography with Ross Miller, but the two parted ways in 2009. For “Roth: The Biography,” Bailey had ample access to the author, his acquaintances and his private papers. He spoke to The Times about harsh reviews of his book and Roth’s formidable self-interest — as well as his loathing for Woody Allen.

How would Roth have fared in 2021?

He gets a pretty hard rap. I understand the ways that Philip has brought this trouble on himself and I don’t hesitate to portray that. You have to bear in mind what Philip would say and did say on his own behalf: “It’s ridiculous! My lifelong friendships have been with formidable intellectual women, Hermione Lee, Judith Thurman, my agent’s a woman, my favorite editor’s a woman, my lawyer’s a woman.” That said, he did not have a monogamous bone in his body. And he was quite capable of sexually objectifying women and making tasteless jokes about it, which he wrote down in his novels.

What do you think of the critical response to your book so far? Laura Marsh had some issues in the New Republic.

That was harsh. I mean, wow. I never thought that a biography of Philip Roth was going to please everybody, and I have not been disappointed. People tend to love him or hate him. And if you are in the latter category, which I think Laura decidedly is, then I cannot be hard enough on Philip Roth. David Remnick of the New Yorker says that I’m “uncowed,” that I let the repellent in, that I present an extremely flawed man. And if you weigh the reviews so far, most are on the David Remnick side.

Philip Roth keeps at full tilt, prying into delusions of immortality and fears surrounding the inevitable in his latest novel, ‘Everyman.’

Yours isn’t the first attempt at a Roth biography. How did Ross Miller’s project fall apart?

The more I learned of the arrangement with Ross Miller, the more appalled I became. Essentially what [Roth] was trying to do with Ross was write his own biography by proxy. My arrangement with Philip is the same arrangement I made with the estates of my three previous subjects, that I have complete independence. He has to provide to me any pertinent documents that I request. He has to make himself available for interviews, he has to encourage his friends, his lovers, etc., to cooperate with me, in exchange for which he gets to vet my manuscript for factual accuracy only. It was radically different than the arrangement he had with Ross.

At one point he approached Judith Thurman to write it, and then Hermione Lee.

Judith never had any illusions about what a steaming pile of [crap] that proposition was. Only Ross could be bamboozled that way. Hermione wanted to do it, but she kept saying, “Philip, I have to honor my obligations.” He wanted her to drop everything and write his biography.

And did he live up to your agreement?

In every conceivable way Philip was extremely proactive those first two or three years of our collaboration. He would send me bulky envelopes two or three times a week. We would meet at his apartment on the Upper West Side or at his house in Connecticut. And he would call me, and sometimes he would call me in an agitated state because he was fretful about something. What you have to understand is that Philip is an obsessive personality at the best of times. And his biography, his only authorized biography and his legacy in general, was foremost on his mind those last years. So, I sort of bore the brunt of that.

How did your image of him change once you got to know him?

Philip never really disappointed me. He was wonderful company. He’s the funniest guy alive. Even at his worst, when he was ranting and raving at his “bitch of a wife,” he was charming and funny and essentially benign. He was very obsessively devoted to promoting his own interests. I can live with that. That’s a very human quality. Later, Philip became something else. But I have to emphasize that core sweetness and decency never entirely left him.

What you have to understand is that Philip is an obsessive personality at the best of times.

— biographer Blake Bailey

Did he lie to you, or only dress up the facts?

Cheever was a deliberate compulsive fabulist, i.e., a liar — and was charming. He was constantly improving on actual life. A lot of good writers do that. Philip meant to be accurate, it was very important to him, but always in his own interests. With Philip particularly, he had transmuted the raw material of his life again and again in his fiction and that had affected his memory. So, he remembered it as it happened in the fiction and not as it happened in real life.

Despite their similarities in tone, Roth had little love for Woody Allen.

Claire Bloom was in “Crimes and Misdemeanors.” She said, “This is a man who doesn’t exist as a human being. There’s something deeply wrong with this man.” Philip thought Woody Allen was a phony pseudo-intellectual who had never finished a book in his life and made all these highfalutin allusions to Strindberg and whatnot. It was all bull—. Anyway, I can assure you they were not kindred spirits. Woody Allen started by being a phony and a bad artist, to Philip, and once Philip became friends with Mia [Farrow], he knew that [Allen] was a truly despicable human being.

What was he like toward the end?

Philip would tell you anything. You would sit there and think, “I can’t believe he’s telling me this. Does he know I’m his biographer? Does he know I’m going to write this down?” Toward the end, he knew he wasn’t going to live much longer and he would say that life was great and he’s going out on a high note. I’m getting verklempt just thinking about it.

Paul Simon was about to take the stage Tuesday night at the Hollywood Bowl when my 26-year-old daughter looked up from her phone: “Philip Roth died.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.