Divorce, quarantine, Stage 4 cancer? Annabelle Gurwitch has to laugh

- Share via

On the Shelf

You're Leaving When? Adventures in Downward Mobility

By Annabelle Gurwitch

Counterpoint: 224 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When Annabelle Gurwitch was in her 30s and 40s, her peak-earner days, she assumed her later middle age would resemble a Nancy Meyers movie. Like Diane Keaton’s character in “Something’s Gotta Give,” Gurwitch expected to while away her sunset years in a well-appointed summer home. Exactly how she’d mount this summit, Gurwitch didn’t know, nor did she dwell on it much.

The problem: Accumulating wealth wasn’t a priority. Though handsomely paid as an actress and host of several TV shows, including TBS’ “Dinner and a Movie,” Gurwitch had been imprinted by her financially unstable Southern childhood. Decades later, the Squirrel, as her friends called her, hung on to every old tatter. Money didn’t dictate her life. In the early aughts, she turned down a lucrative position with a daily radio show because the hours would’ve deprived her of mornings with her then-kindergarten-age child, Ezra.

Gurwitch tackles the hilarious and humbling consequences of her retirement non-plan in her new book, “You’re Leaving When?: Adventures in Downward Mobility,” which is a lot more upbeat and plot-driven than it sounds. She sees herself as part of “the never-tirement generation,” and she has no plans to leave her one asset, her longtime home in Los Feliz, constructed over a literal fault line.

“I made my choices,” she says over a video call from her art-packed living room, “and we’re lucky if we get to make choices at all in life.” At 59, Gurwitch has realized her true identity: “I’m not the owner of the summer home; I’m the guest at the summer home” — though her fuzzy black sweater and tousled bob still project Meyers’ shabby chic.

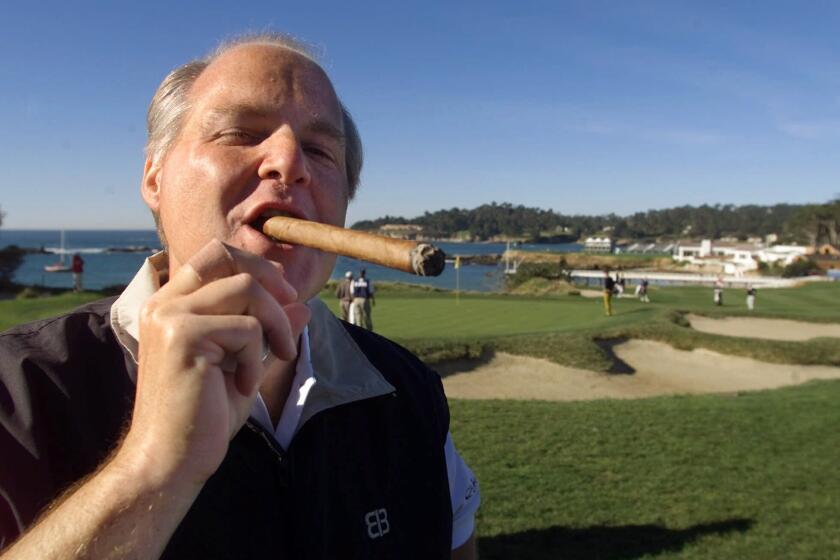

Like most of us in this pandemic, she’s not going to the Hamptons for a while: She’s too busy navigating life as an empty nester, divorcée and, most recently, a cancer patient. Initially going in for a COVID test, Gurwitch was diagnosed last year with Stage 4 lung cancer, an experience she chronicled for the New York Times. “It’s the same diagnosis as Rush Limbaugh,” she informs me. “I’ve asked to get transferred to a different diagnosis.”

How does a country react to the death of a man who spent much of his life leveraging and exacerbating political, social and cultural divisions? Right along party lines.

When Limbaugh died a few days after our interview, Gurwitch’s response was “complicated.” She’s holding steady with her treatment plan: gene-targeted medication to suppress the growth of her tumors and scans every few months (“the term ‘scanxiety’ is a real thing,” she says).

Since 2006, she’s written and edited one anthology (“Fired!” inspired by her experience getting canned by her one-time idol Woody Allen), and four comic memoirs, including the bestselling “I See You Made an Effort,” nominated for the Thurber Prize, and “You Say Tomato, I Say Shut Up” with then-husband Jeff Kahn, which they also developed into a play that toured more than 30 cities.

Gurwitch calls “You’re Leaving When?” “a love letter to the city” of L.A. and “a book for those who have reinvented themselves at least a dozen times.” In chatty, gimlet-eyed prose, she explores a certain glamorous but down-at-the-heels existence that SoCal’s house-poor but friend-rich know all too well. Want to eat at a world-class Chinese restaurant in the San Gabriel Valley with all your besties? Easy, but good luck finding the money to repair the plumbing. She’s now logged 30 years here — not bad for a person who used to call herself “an expatriate from New York” in every bio.

But by the time she was 55, life had destabilized. “I wasn’t sure who I was anymore,” Gurwitch writes in the book. “So many of the daily activities that defined my identity — my life as a daughter, wife, and mother — had fallen away.” First came the divorce, then Ezra went to college and adopted they-them pronouns in the process. (They also celebrated four years sober in February.) With a mortgage to pay and no interest in moving, the Squirrel had only one survival strategy: She’d rent out her spare bedroom. That would solve the financial problem, but not the looming philosophical conundrum, which in COVID times is a near-universal one: “How do you intentionally create a meaningful life when one way of life completely ends?”

That’s when she had what she calls “my Blanche DuBois moment. All I had left as a solo person was the kindness of strangers.” It was a kindness she returned. “I thought opening up my house was going to destroy me,” Gurwitch says, “but instead it turned out to be a huge salvation.”

After a few years of renting to various friends of friends, she put up two housing-insecure people in their 20s, a couple with matching face tattoos, through a program called Safe Place for Youth. Gurwitch is honest about her initial impressions of Keyawna and Jesse. With one hand, she’s setting out fresh towels and flowers for their arrival and with the other she’s hiding jewelry and gobbling up a high-end steak she doesn’t want to share.

The closer Gurwitch gets to their lives, which she shared with their permission, the more she sees how limited their options really are. She looks back at her own narrative — of having “singlehandedly overcome my chaotic childhood” — and finds the odds have been stacked in her favor. “It was a transformational experience for all of us,” she says. Gurwitch is turning “You’re Leaving When?” into a pilot for HBO, fictionalizing her time with Keyawna and Jesse.

Not all of the author’s post-divorce pursuits are quite so high-minded. She learns that some of her peers have opted for “a facelift down there,” and so, in an uproarious chapter called “Lubepocalypse Now!” she treats herself to what the clinic calls the Mona Lisa. Preparing for her first post-surgery liaison, Gurwitch heads to Lassen’s for organic lube but forgets her glasses. A clerk reads ingredients to her aloud and she heads home with an armful of samples. A few hours later: “Houston, we had liftoff.”

Emily Rapp Black lost her toddler to Tay-Sachs disease. She talks to a fellow griever about ‘Sanctuary,’ her follow-up memoir about rebuilding a life.

When Gurwitch isn’t taking classes in ukulele or Awareness Through Movement or writing coffee shop style with her “regulars” on Zoom, she records the “Tiny Victories” podcast with co-host Laura House, which celebrates such triumphs as a Silver Lake enclave banding together to catch three escaped chickens. After her diagnosis, it’s become all the more crucial to hold close the small pleasures. But don’t you dare call cancer “a gift” that has opened her heart.

“If I ever say something like that, you’ll know I’ve had a mental breakdown,” Gurwitch says. As an atheist, “I’m not going God. The only thing I really need is a good doctor.” Choosing an oncologist, “I went with the one who has the bedside manner of an open grave. I prefer that kind of honesty. I want it straight.”

There are a few other things she requires: “I need kittens,” she says as a smoky gray fellow dashes onto her keyboard (and later disconnects our Zoom). “And a good glass of Pinot Noir.” So far, she’s avoided seeing “the guy in Topanga who has a machine in his garage that emits Tesla currents” that purportedly heal cancer. “I was like, ‘No, I’m not even going to date this guy,’ which I might’ve done a few years ago.”

For “You’re Leaving When?,” Gurwitch was determined to avoid one of the workhorses of memoir, the divorce book. But what about the other perennial?

“I have some thoughts about the cancer memoir,” Gurwitch says. “I’m thinking of titling it, ‘I’m Sorry I Don’t Look Sick Enough for You.’” I blush, remembering how I told Gurwitch she looked great at the beginning of our call — she did!

For a moment, our conversation turns emotional. “I hope I live long enough to write that,” she says. “I really don’t know the future,” she adds, wiping away tears, “but I’m accepting that. I really don’t know how long I’ll be here.”

I ask how often she allows those thoughts in. “At some point, I think about it every single day. And I just try not to get teary. Or to normalize the thinking” that, as the saying goes, life is short and you could be hit by a bus, so YOLO. “I’ve been hit by the bus and now I’m getting dragged,” Gurwitch says.

Later in the day, she will push away those thoughts and summon her inner Jewish mother — “actually, I’ve gone full grandmother” — and drive to Ezra’s a few blocks away. Ezra had moved back home after school, but left again to mitigate the risk of COVID. Sometimes the two just chat, but the other day she delivered latkes in a street corner handoff “like it’s a drug deal in the ‘80s” — kindness not for a stranger, but her child — and herself.

Out with the essay collection ‘No One Asked For This,’ David talks candidly about nepotism, Pete Davidson and a terrifying, hilarious web of neuroses.

“Life has changed and the universe did not provide the perfect parking space,” Gurwitch says with a shrug. “So what are you going to do? These are the moments when the real humor begins.”

Wappler is the author of “Neon Green.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.