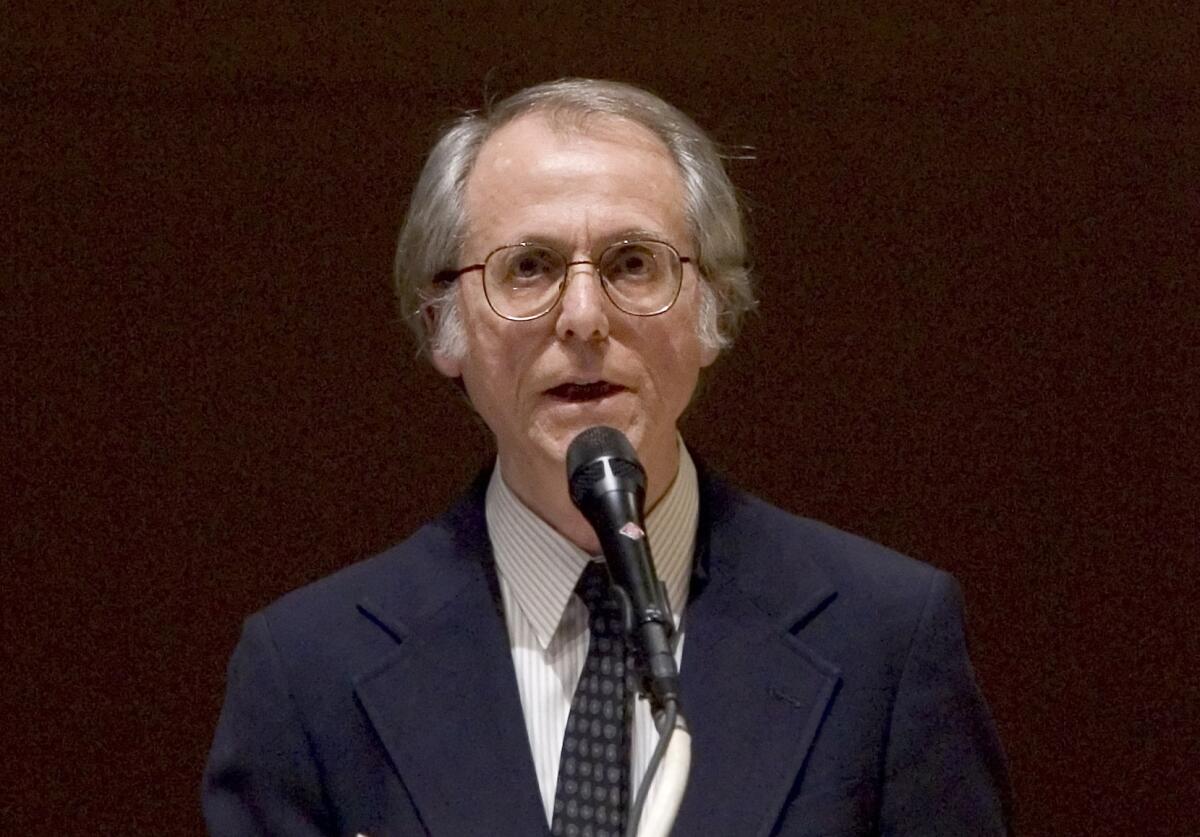

Don DeLillo’s prescience is a mystery even to his acolytes

On the Shelf

The Silence

By Don DeLillo

Scribner: 128 pages, $22

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Don DeLillo has written about America in the 20th century so acutely and capaciously that he’s become a fixed star in our literary firmament. His novels — think “Underworld,” “White Noise” and “Libra” — pack narrative, history and ideas into each line, with dialogue that sounds like no one else’s. His work is darkly funny, though it’s hard to extract a sentence that shows it. He’s also influenced some of the smartest writers of the next generation, but — as with the humor — it can be hard to explain how. Even for people who are good at words.

“What it was doing didn’t seem to be obvious on the surface,” Rachel Kushner says of “Great Jones Street,” one of the DeLillo novels she read when she was trying to learn how to become a writer. (Since then, she’s been shortlisted for the Booker Prize and a two-time National Book Award finalist.) “It didn’t seem like something you’d ever want to try to emulate because I couldn’t even figure out what it was doing, much less copy it.” And, she adds, “That was exciting to me.”

Jonathan Lethem did try. “Now I can confess it very freely because it was like some other person, it was so long ago,” he says. Readers might notice “slavish, DeLillo-esque” dialogue in his 1997 novel “As She Climbed Across the Table,” for instance. “It was a 26-year-old upstart who was doing that, not me,” he says, laughing. Three decades later, Lethem is a bestselling author; his many awards include a MacArthur; he teaches at Pomona College. He’s also got a book coming in November, “The Arrest,” a futuristic non-dystopia with a kinship to DeLillo’s new book.

If you want to reach Don DeLillo, don’t try to email him; he doesn’t email.

That’s right, a new book. “The Silence,” arriving Oct. 20, is a powerful, short novel begun years before the arrival of COVID-19 and set two years afterward. On Super Bowl Sunday, 2022, a virus has just taken hold. Hospitals are overcrowded, the electrical grid seems to have gone down and most Americans are left to what might be a state of panicked chaos. So it seems, anyway, to the characters in a lofty apartment waiting for the football game to start.

Kushner has already read it. “The thing that mystifies me the most, coming to a concentrated form in ‘The Silence,’ is how he reads the future in the weave of the present,” she says. “To do that, you have to be really interested in the historical moment in which you’re living.”

She and Dana Spiotta, another acclaimed author who counts DeLillo as a major influence, have talked about this; Spiotta calls it second sight. “He’s got a special receiver that we all don’t have. He can hear things in the culture, he can see things before everybody else,” Spiotta says.

Almost every reader I’ve spoken to first came to DeLillo via “White Noise,” his 1985 National Book Award-winning academic satire with an environmental catastrophe on the horizon — an airborne toxic event — that doesn’t quite disrupt the comfortable lives of its characters.

“It was my first experience of seeing a social critique that spoke to my moment,” says Joe Salvatore, a writer and professor at the New School in New York City. “It seemed so crisp and so perfect; there seemed to be a very clear, cynical, gravely observant force behind it. But I almost felt that the author of that book was calibrating the kind of message he wanted to send.” Salvatore went on to read all of DeLillo‘s novels and, in 2017, taught a seminar on his works.

“‘White Noise’ really resonated with them as I thought it might,” says Salvatore of his students. But in the first semester coinciding with the Trump administration, DeLillo’s 1971 debut, “Americana,” made a surprising connection as well. “Some of the men in ‘Americana’ are proto-Trumpians,” Salvatore said. “You can’t imagine how many times students were looking at the present moment through these DeLillo books.”

Perhaps no other medium has better helped us process 2020. Our fall books special brings you the books and authors who’ve helped make sense of it.

“He’s a master for me,” Lethem says. “Happily, his work has never stopped replenishing me.” This even though — or perhaps because — he hasn’t analyzed it. “I’ve never actually written about Don’s work,” he says, having crossed paths with DeLillo enough to refer to him by first name. “There’s a way in which I am still in a kind of awed relation to the work of his that overwhelms me. Something I’m tiptoeing around still.”

Associated with the “systems novel,” DeLillo often has (and earns) a reputation for approaching his subjects from a philosophical distance (that lofty apartment of the mind). When compared to the expressive realism of, say, Marilynne Robinson, DeLillo’s bracing intellectualism can seem like an alien intelligence. Some critics find his works cold. (I’m not one of them.)

Kushner vouches for his personal warmth — she considers him a friend and refers to his insistence that he’s just a boy from the Bronx. But, she emphasizes, he was a Jesuit-educated boy from the Bronx.

Spiotta, who teaches at Syracuse University, plunged into DeLillo as a young reader and aspiring writer. “The idea that I really took to heart is that it’s good to be at the margins, not the center of the culture, so that you can interrogate the culture. It’s this countercultural act to write a novel,” she says. “Writing is a form of thinking, writing is a form of seeing.”

She’s thought a lot about how his writing works — so much so that her explanation to me was long and recursive and informative and too long to fit here. The short version: “He does write sentences like nobody else,” she says. “Paying attention to the sound, the cadence and then to paragraphs and space breaks and chapter breaks. It leads to this structural density. The structural stuff with DeLillo is really big for me.

“I don’t just mean the structure of ‘Underworld,’ being able to use a preface or coda … it’s about the freedom to use structure to create meaning.” Even in his shortest books, she says, “you only can apprehend it once you get to the end and can see the whole thing; you have to go back and read it again.”

Critics are often cool to these shorter novels, of which “The Silence,” at 128 pages, is definitely one. Readers who embraced the vast sweeping celebration of America’s 20th century in “Underworld” or the brilliant historical inversions of the Kennedy assassination in “Libra” might be among the least receptive to the short, spare conversation with a general that makes up 2010’s “Point Omega” or the quiet, grief-filled “The Body Artist” of 2001.

But, I’d say, if DeLillo has been writing the American century, he’s also been writing the end of it. If that loss can be hard to read, it doesn’t make it any less true or the work any less powerful.

“Falling Man” (2007) remains one of the best 9/11 novels; everything DeLillo has done since the turn of the millennium, including “Cosmopolis” and “Zero K,” has pointed in one way or another to America’s dissipation.

In Don DeLillo’s new novel, “Zero K,” words have come unattached from the things they mean.

Kushner once asked him about his uncanny, unsettling futurism. “I said, knowing you and how mild you are, then reading your work, it’s very unnerving how much you can see into the future. And he said, ‘You think it’s unnerving for you.’”

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.