Is Trump our fault? Two authors spar over citizenship, identity and complicity

On the Shelf

Laila Lalami and Ayad Akhtar

Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America

By Laila Lalami

Pantheon: 208 pages, $26

Homeland Elegies

By Ayad Akhtar

Little Brown: 368 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In Laila Lalami’s “Conditional Citizens,” the Moroccan American author tells a story both sweeping and intimate about what it means to be American. It’s her first book of nonfiction, a swift intellectual history that nails the present moment in the context of our nation’s pockmarked past.

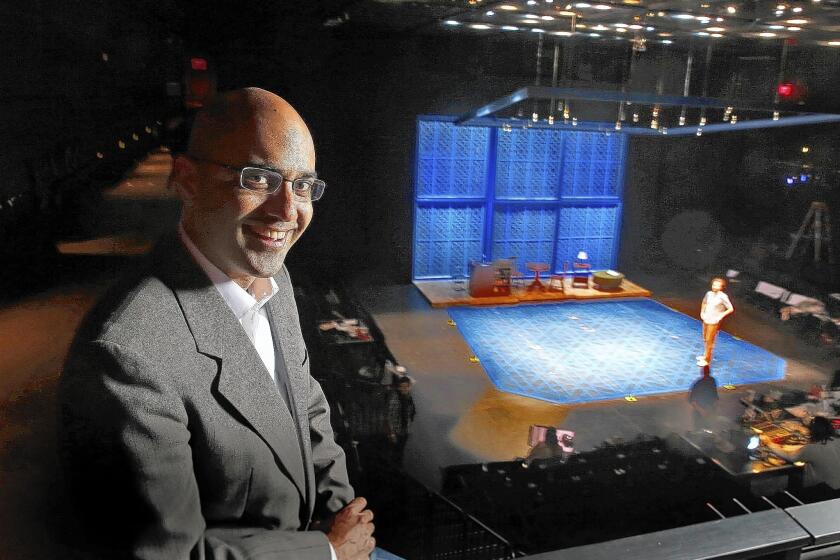

Ayad Akhtar, who won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for drama for his play “Disgraced,” is mirrored in the narrator of his new novel “Homeland Elegies.” The multilayered narrative features a prize-winning writer, his Trump-loving father, his disenchanted mother, the frustrations of being a broke artist and the seductions of neoliberalism. Akhtar’s creative interests are part of his public life; in September he was named President of PEN America.

They joined The Times via Zoom to talk about their new books and more; the conversation has been edited.

Laila, your book is nonfiction but you’ve included more of your life than you typically do.

Laila Lalami: There really was no other way to write about the experience of citizenship and the boundaries of Americanness.

AA: I can’t imagine the book without that. I felt connected to the struggles that you were articulating. Without that personal point of view and the poignancy of those episodes, it would be a very different book.

LL: Thank you very much. Ayad, I started reading “Homeland Elegies” this week. It’s the sort of book that arrived at the exact time that I needed it.

The solitude of social distancing gives the faithful an opportunity to reflect on the core principles of Ramadan.

Both of your books deal a lot with how America has defined who is “us” and who is “them.” What inspired you to begin?

LL: I was watching the Democratic National Convention in 2016 and Khizr Khan and his wife, Ghazala, showed up to talk about their son. When he pulled out his pocket Constitution, it got me thinking about citizenship — who gets to be American and under what circumstances. It was very clear that for people like him, and people like me, who are naturalized citizens, you get to be American when you are grateful. But if you exercise other freedoms, like the freedom to criticize, then everything changes. Suddenly you hear things like “Love it or leave it,” “Go back to your country,” and so on. That’s where the adjective came from, that we’re conditional citizens.

AA: The overture of “Homeland Elegies” is the argument of the book. Yes, I’m Muslim, whatever that means. And yes, it’s been hard for folks like us post-9/11. But it wasn’t the exclusion on the basis of identity or race or religion that awakened an understanding of the sources of our crumbling republic. We are in a situation which transcends the individual dilemma of even this Muslim writer, who’s going to tell you about all the consequences of America’s inability to deal with its own tragedy. Even though that’s the narrator’s perspective, there is still even a bigger perspective when it comes to us as Americans, which is that our country is crumbling. And so the argument is less about belonging and more about what’s happened to us as a nation. Which is not to say that the belonging thing isn’t an important part, but I think I’m trying to straddle both things.

When you say trying to straddle both things, what do you mean?

AA: I knew that no matter what I write, everyone’s going to be like, Oh, it’s about some Muslim thing. [Laila laughs] I could write about the interiority of a snail brilliantly, and it would be, Oh, it’s some reflection of Muslim consciousness, right?

LL: You can say “this shirt is red” and people say, how does that relate? [laughs]

AA: Yes! And so I had to own that, and I wanted to write a book that spoke to my fellow American citizens, all of them. By enfolding the dilemmas of belonging and the contradictions of American identity into the substance of the book, it enabled me — I hope, I believe, I devoutly wish that that is a conveyor to a bigger picture.

Lawyers for a woman who accused President Trump of unwanted kissing and groping in 2007 say records from his own calendar help prove her claim.

Ayad, you weave in questions about America’s history as a site of wealth extraction, which is basically about capitalism. The father in the book is enamored with Donald Trump, who has tricked everybody into thinking he’s rich and now taken over the nation.

AA: You know, I think of Trump as the expression par excellence of contemporary capitalism, because he’s the expression of what debt makes possible. His career is an impossibility without the franchise of debt. The gap between real value and perceived value in debt is actually the exact same gap between truth and appearance in Trump. In a way the book makes a case that America is a casino and my dad and I are marks.

LL: [laughing] I love that!

AA: To me, Trump is not the problem. He is our president. He is who we have watched for 14 seasons pretend to be a boss. We are the people who have somehow substituted entertainment for thinking, and entertainment for politics. He didn’t do that. We’ve done that. So this idea of blaming Trump to me is just — it’s not going to get better until we understand what we’ve done.

LL: I like the fact that the father is a Trump supporter, because I recognize this character. Even though Trump overwhelmingly is rejected by American Muslims, he still managed to get a small portion of Muslim votes in the last election. One of the things that I was amused by as the father here is a cardiologist, obviously a very educated man. So you wouldn’t expect that he would fall for Trump. My parents happened to be visiting me during the last election and they didn’t go to college, and they were onto him. They saw right through the whole thing — and that’s because they have experience with crooks! [laughs]

AA: Right. [laughs] That’s great.

Playwright-novelist Ayad Akhtar, whose work has dealt with religion, tradition and sexuality, now offers ‘The Who & the What’ at La Jolla Playhouse.

LL: The appeal of Trump doesn’t necessarily have to do with education. It has to do with familiarity and what people see in him. My parents saw a crook but the character in this novel sees a highly successful businessman, someone who, in some sense, he hopes to replicate. I do agree that Trump is very much a symptom. He didn’t come out of a vacuum. But I don’t know that the blame for him can be laid squarely at the foot of some “us.” You can’t really talk about his success as a reality television star without talking about all reality TV, the corporatization of media. All of these things are connected. It’s not entirely the choice of consumers or citizens.

AA: I think it’s an important distinction you’re making, and I think it’s an accurate one. Trump doesn’t represent everybody. Right? His vulgarity is not reflective of the personal vulgarity of the entire American nation — though I think there’s a case to be made for that. But I think the wholesale changes — politically, legislatively, economically, at the level of ideology — we are responsible for those things. We are responsible for the fact that we sit on our phones and our consciousness is monetized upward of seven hours a day now. I do believe we have a greater responsibility. Now maybe, as human beings, we have limited agency. Well, then let’s stop calling ourselves an enlightened democracy. If that’s the truth, then let’s start calling ourselves a corporate totalitarian system, or whatever it may be.

LL: I think we both agree and disagree. If we are all responsible, all it would take would be: I delete Facebook, I delete Twitter, I delete Instagram. I stop watching TV. I have freed myself! I think that’s idealistic and admirable; I don’t know how practical it is. We are hitched to everybody else in the social contract, we are all stitched together.

AA: Sure, but I don’t think I’m suggesting that social media is the only reason that we have the political situation that we do. Maybe a more synoptic way of putting it is that we seem to evince less and less interest in citizenship and more and more interest in consumerism. We are less citizens of the republic now and more customers to reality. That’s on us. And yes, there’s no way to just stop that. It’s been so many years in the making. But I think I can’t absolve my own participation, my parents’ participation; all of that has gone into the country we have become.

LL: Yes, our status and our duties and our roles as citizens are the only things that stand between us and being essentially only consumers and nothing else, basically having no other rights.

AA: On my end I only hear agreement.

LL: We did actually agree!

Over the last three months, 17 writers provided diaries to the Times of their days in isolation, followed by weeks of protest. This is their story.

Both your books include incidents of white audience members asking not-smart questions at literary events related to being Muslim. How often do you face those kinds of questions?

LL: To go back to something we were talking about earlier, it’s impossible for me as a writer not to come across questions about being Muslim, or at the very least questions about politics. That is the lens that is applied because of accidents of birth: the fact that I’m a woman, the fact that I’m brown, the fact that I’m a naturalized citizen. I sometimes feel envious of writers who get to go to literary festivals and talk about craft.

AA: The way that I deal with that is the general strategy of answering the question you wish you were asked. That requires a bit of rhetorical gymnastics from time to time.

Ayad, one of the characters tells the narrator that he wants him to stop telling complicated stories about Muslims because they are so under attack in America.

AA: I think his critique is valid. I mean, I’m not going to listen to it but I think it’s valid. It’s a debate that happened between Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston in the Harlem Renaissance, where Langston was very clear about the responsibility of artists of color to represent their own kind in ways that the white folk were not going to take advantage of, and Zora’s response was no, the only thing that matters to me is art. I think there’s a third position, something like social and philosophical truth. We all stand in the light of truth; we are all implicated; we’re all flawed, we’re all capable of great goodness. To me, that’s the purview of great literature.

LL: I think this is something nonwhite communities go through. The idea is that you’re writing for everyone else, first of all, is an interesting assumption. Ayad’s work engages with issues that are relevant to American Muslims, but it’s also very different from my experience growing up in Morocco, my experience of being Muslim. The writer Viet Thanh Nguyen has this concept of narrative plenitude. When you have only a handful of stories, there’s so much pressure on them to represent everybody’s expectations. You can easily have Sidney Poitier syndrome, where people want you to have characters that are perfect in every way. That is not real.

AA: If I could just add something to what Laila said very eloquently, I think that increasingly we’re in a dilemma. Artists are being asked, increasingly, to become cheerleaders or advocates for points of view. Audiences are increasingly reading work for its representational politics, as opposed to the aesthetics of craft or narrative storytelling, and that what is good is no longer necessarily a good story. And I think that is dangerous for me creatively. I’ve been trying to figure out how to do something good my whole life, not how to do the right thing my whole life. It’s a very complicated moment.

From ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ to ‘The Birth of a Nation,’ stories that flatten usually falter

Kellogg is formerly books editor of the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.