How racism haunts America, and other lessons from Tananarive Due’s ghostly speculative fiction

Ahead of Juneteenth, the author opens up about the emancipatory quality of speculative fiction and the setting that connects several of her books.

Welcome back to the L.A. Times Book Club newsletter.

I’m Jim Ruland, a novelist and punk historian, and in today’s newsletter I’m going to take a look at Black fiction that reimagines the past and speculates about the future.

Science fiction writer Octavia Butler, who was born and raised in Pasadena, opens her 1993 novel “Parable of the Sower” in the year 2024. In it, income disparity and climate change bring society to the brink of collapse, which doesn’t exactly bode well for what will likely be a fractious presidential election.

“Octavia was deeply offended by the societal ills she saw around her: poverty, racism, political oppression, and disregard for our natural environment,” Tananarive Due wrote in her essay “The Only Last Truth” part of the anthology in “Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories From Social Justice Movements” edited by Adrienne Maree Brown and Walidah Imarisha

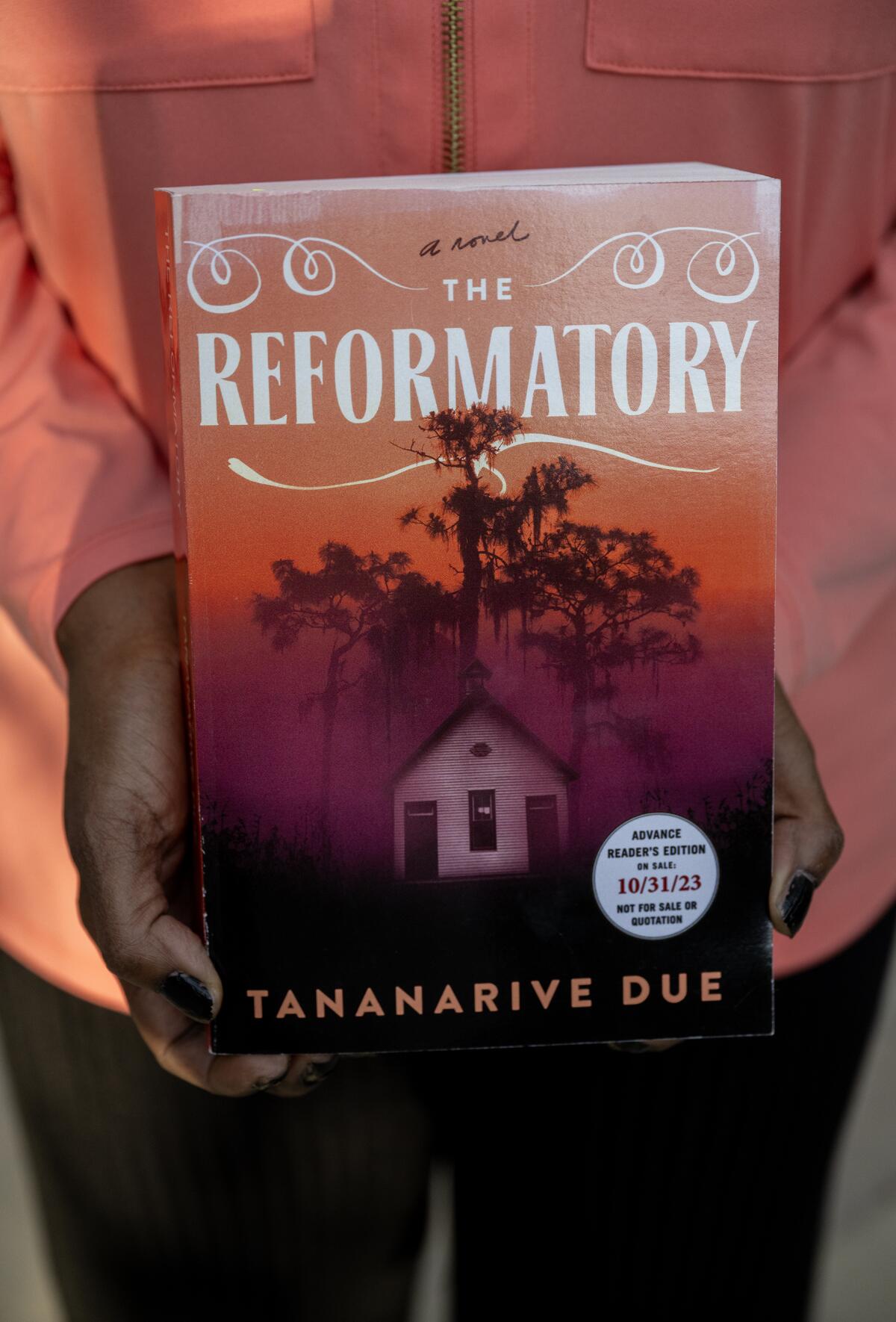

Due’s novel “The Reformatory” wrestles with the horrors of a segregated reform school for boys in northern Florida during the Jim Crow era.

Ahead of Juneteenth and following her Bram Stoker award win, I talked to Due about her new book and the power of speculative fiction to address historical inequality.

In your essay in “Octavia’s Brood,” you discuss Octavia Butler’s use of speculative fiction to get at larger historical truths. “The Reformatory” does something similar, no?

Yes, that’s a great observation. That technique is so effective when Octavia uses it to create science fictional worlds that also reflect our own. So while “The Reformatory” is a ghost story, and it’s set during the Jim Crow era, I really did hope that readers would see how it resonates with issues that persist in the here and now, especially as it pertains to the criminal justice system and the ways that white supremacy dictates different outcomes for different people depending on the color of their skin.

Is “The Reformatory” rooted in family history?

The personal story of the Reformatory is actually a heartbreaking one: My great-uncle Robert Stephens died at the Dozier School for Boys in 1937. He was buried in an unmarked grave and largely forgotten by his family. My mother never told me about him, and I suspect she did not know that he existed. I have a relative who was named for Robert Stephens but didn’t realize for whom he had been named.

How did a story that engages in the supernatural emerge from such a personal story?

As soon as I heard of his existence in 2013, I knew I wanted to write about him. I knew that I wanted people to remember his name, and most of all I knew that I wanted to give him a different story. And since I couldn’t stomach the idea of writing a novel about a place where we’re constantly seeing children being murdered or assaulted, I knew the only way I could tell this story would be to use ghosts.

Ghosts would signal that there have been violent acts in the past and that children died, but we wouldn’t have to be subjected to killing after killing after killing. The fantastic elements of a ghost story gave me the freedom to delve into the more mundane horrors and indignities people suffered during the Jim Crow era.

You’re reading Book Club

An exclusive look at what we’re reading, book club events and our latest author interviews.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Juneteenth is next week. Can you talk about the emancipatory quality of alternate futures and counterfactual narratives?

There are aspects of American history that are so horrific that politicians and school boards across the country are scrambling to ban students from even learning about it. Unless people understand how forceful economic and racial oppression has been, there is no framework to understand why there is so much poverty in our community, or why the criminal justice system still has so many biases against Black people in particular, but people of color in general. So it is incredibly freeing to be able to use a fantasy element like ghosts to walk through that history while also giving readers peeks at a better future.

“The Wishing Pool” is coming out in paperback in October and has stories set in Gracetown, the setting for “The Reformatory.” Do they all take place in the same universe?

Yes! I began writing Gracetown stories about 15 years ago with the premise that it was a rural town in the South where children are more sensitive to acts of magic or future sight. I created Gracetown after my parents moved back to my late mother’s hometown of Quincy, Fla., as a way of embracing that part of my family history. I grew up in the suburbs, so I didn’t know anything about rural life and wanted to explore that in my fiction the way William Faulkner did with Yoknapatawpha County. They are the same town, the same universe.

One character vows never to go to Gracetown again. Will you continue to revisit Gracetown?

My next novel will also start in Gracetown … although most of it will be set in California. I am always tempted to write Gracetown stories with child protagonists, but I also want to be careful about returning to that well too many times.

(Please note: The Times may earn a commission through links to Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.)

More Black fiction in the L.A. Times

Maurice Carlos Ruffin explores the lives of a mother and daughter who are sold into slavery and sent to work in the French Quarter in “The American Daughters.” Lauren LeBlanc writes: “Ruffin creates an intimate and atmospheric portrait of life in New Orleans through interior scenes divided between opulence and abuse.”

Time is out of joint in Phillip B. Williams novel “Ours.” In Ilana Masad’s review, she quotes the author’s intention “to write an epic taking place during the antebellum period where slavery is not the main antagonist without disregarding or disappearing the enslaved.”

Percival Everett has been exploring Blackness in America his entire career, but the adaptation of his novel “Erasure” introduced his work to a wider audience. His latest novel, “James,” is a reimagining of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” through the lens of the enslaved character Jim.

And if you’re dying to know more about Tananarive Due’s trailblazing career in Black horror, Paula L. Woods’ profile is a must read: “There can be something strangely comforting about horror when you’ve actually been through trauma,” [Due] says, “because on one level a book or a film is a validation of your emotions and fears.”

The Week(s) in Books

A.D. Carson on Questlove’s new book “Hip-Hop Is History”: “Histories can claim to be definitive, but they will always raise questions about what was left out and why.”

Lorraine Berry talks to Patrick Nathan about his new novel “The Future Was Color”: “I was focused in writing this book on the kind of balance between being politically committed and wanting to have a life.”

Bethanne Patrick visits Harlan Ellison’s house and talks to J. Michael “Joe” Straczynski, the literary executor of Ellison’s estate: “When you walk into this house,” he says, “you are walking into Harlan’s brain.”

Ever wondered how much Supreme Court Justices earn for book advances? David G. Savage has the verdict.

Support independent Black-owned bookstores in L.A.

Eclectuals Bookstore: Online bookstore based in Lakewood.

Malik Books: 3650 W. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Suite 245, Los Angeles 90008-1700. Open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday through Saturday.

Octavia’s Bookshelf: 365 N. Hill Ave., Pasadena 91104. Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. Closed Monday.

Melanin in YA: Online bookstore specializing in books for young adults.

Reparations Club: 3054 S. Victoria Ave., Los Angeles 90016. Open 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday to Saturday; noon to 5 p.m. Sunday. Closed Monday.

Shades of Afrika: Two locations, 1001 E. 4th St., Long Beach 90802, and 1390 W. 6th St., No. 100, Corona 92882.

The Salt Eaters Bookshop: 302 E. Queen St., Inglewood 90301. Open 1 to 6 p.m. Wednesday through Friday; noon to 5 p.m. Saturday. Closed Sunday through Tuesday.

Thanks for reading. I hope your Father’s Day weekend is full of good books! I’ll be back in two weeks with a dispatch from South America.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.