Brazil’s lost movie palaces find new life in ‘Pictures of Ghosts’: ‘Cinema has a way of mythifying’

The first time Brazilian writer-director Kleber Mendonça Filho (“Neighbouring Sounds”) visited L.A.’s historic Broadway Theater District, he plotted a return with a camera to record the dozen movie palaces there, built between 1910 and 1931. Instead, he went local, digging into his collection of self-shot VHS, Betacam and Hi8 tapes, as well as capturing new footage of his hometown of Recife, Brazil, now the star of “Pictures of Ghosts,” his poignant, deeply personal documentary. A huge hit in Brazil, it’s split up into three chapters, beginning with the modernist apartment featured prominently in his early work, then the once-elegant movie houses where he fell in love with moving pictures, and last, a meditation on the future of these neglected architectural gems. It’s a project he’s been thinking about since he was a teenager standing in a supermarket, suddenly realizing it was a former cinema. “I looked up and I could see the portholes for the projection,” said Filho. “And I realized how much it says about time, the industry and how society behaves.”

We’ve mapped out 27 of the best movie theaters in L.A., from the TCL Chinese and the New Beverly to the Alamo Drafthouse and which AMC reigns in Burbank.

Did you always know that someday your old footage could be put to use?

I always had it in the back of my mind. I was also aware at an early age that things you keep — a piece of paper, photographs, video — become more interesting as time passes. Time is usually generous. A picture of two friends this afternoon will be more meaningful in 15 years, because they’ll change physically. I consider myself an amateur archivist. I’ve done quite a good job with the tapes. I kept them in a vertical position in my office over the years. In 2002, I copied everything to MiniDV, because I was afraid that the VHS would go bad. Recently, I went back and re-digitized everything again from the original tapes. I wanted to do it myself. I wanted to re-discover the material.

There’s a sense of you finding your way in “Pictures.” Did it take a long time to figure out a structure?

We always feel lost making films at some point. This was a very tricky film, because it doesn’t have a script. Sometimes I knew where I was going, then I’d find something and it’d take me to the right or the left. But once I thought about beginning the film with [my family’s] apartment, I thought that’d be strong. I thought, “I have a film.”

You’ve said that during the research phase, you discovered that every household has an archivist.

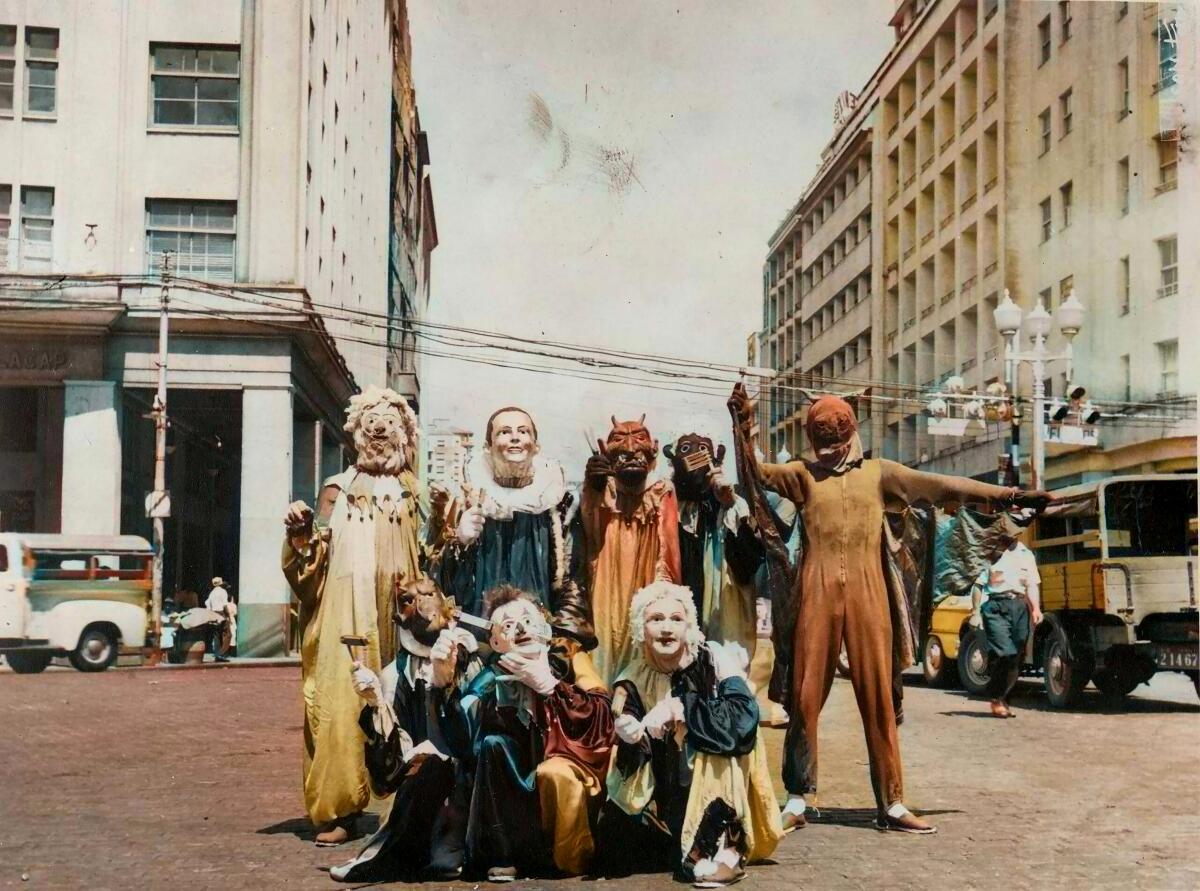

It’s true. But it isn’t always someone you expect. The obvious role would be played by a grandmother or grandfather, because they’re older. But sometimes the archivist is a 50-something aunt or a 24-year-old nephew who happens to love photographs. I wrote on my Instagram account that I was making a film and needed images of Recife in the past. I opened a special account on Gmail, and the pictures began to pour in. It was beautiful. It was like, “You have 16 new messages,” and each message came with a picture.

From ‘Barbenheimer’ to ‘Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour,’ people are going to cinemas again. But a post-pandemic, post-strike Hollywood has its work cut out for it.

What images instantly sparked joy?

Pictures [where] people were just happy to be in front of cinemas, with the marquee or a poster or a line of people in the background. That was precisely what I needed. I’m fascinated looking at old pictures, because someone is standing there, but I’m actually zooming past the main character and looking at the street or at the lady with a dog or the cars in the background, because it says a lot about time and life in society.

Talk about Los Angeles from the perspective of a dedicated moviegoer.

As an outside observer, I think Los Angeles has amazing options to discover films. I’ve been to the AFI. Last night I was at the Egyptian. The Vista is reopening. I was at the New Beverly on Sunday to see “Touch of Evil.” I think it’s only natural that a place like the Egyptian should be renovated every 30 years, because it’s part of history. I think L.A. has the obligation to keep its heritage going.

What about as a film critic and festival programmer from elsewhere?

What my American friends don’t realize is when you come to the U.S., like I did for the first time 30 years ago on a holiday, it really felt like I’d been here. You’re bombarded with Hollywood images from an early age, they’re burned into your brain as a non-U.S. citizen. So when you come to L.A., you’re very much inside a physical vision of cinema. What I’m trying to say is that I was emotionally connected to L.A. even before I came here.

How did the residents of Recife respond to “Pictures”?

It’s funny: The crowds in the city think it plays better for them than for anybody else. But I was in France three weeks ago for the French release, and, of course, they get it. It’s like saying, “You’ll never understand ‘Chinatown’ because you’re not from L.A.” Cinema has a way of mythifying. Like, with [my second feature] “Aquarius,” we shot in a building about a mile and a half from where I used to live. Now, because of the film, the place has become a tourist site where people take selfies. Or Matthew Perry’s death now, people are taking flowers to the “Friends” [apartment] building in New York City, but it was just a facade. [The “Friends”] never lived there. But they lived there in imagination and fantasy.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.