Static camera angles, minimal lens changes and limited lighting sets this ‘Barry’ scene

The final season of “Barry” left viewers with many indelible images. The giant, sand-filled, human-devouring NoHo Hourglass. The rocket grenade attack gone wrong in one masterful, hillside shot. A standoff that left dozens dead in the wink of an eye.

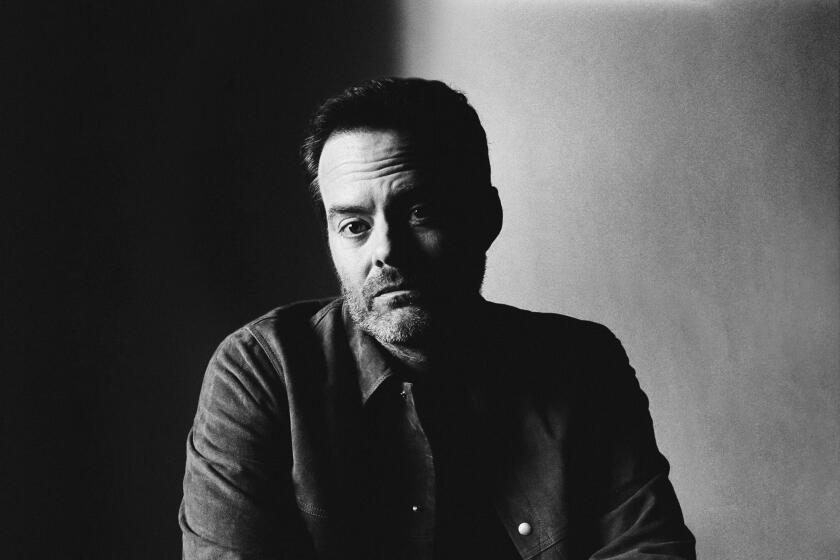

Though cinematographer Carl Herse shot all those scenes, none appear in the “tricky legacies” episode for which Herse earned an Emmy nomination. That’s the one that shows Bill Hader’s hit man Barry and Sarah Goldberg’s actor Sally abruptly living under assumed identities in an isolated house on the Great Plains (actually shot in Lancaster, its surrounding hills digitally removed) with their 8-year-old son John (Zachary Golinger). They’re hiding from the law, the Chechen mob and whoever else wants to kill them.

Herse, who’s lent his expressive yet naturalistic eye to such shows as “The Last Man on Earth,” “Nathan for You” and “The Afterparty,” applied a more refined artistry to the time-jump piece. The idea was to understatedly imply that things had changed. It worked so well that, friends he watched the episode with thought it was one of the dream flashback/fantasy sequences Barry had had in the season’s earlier episodes rather than a narrative leap forward.

The characters on HBO’s brilliant comedy-drama never stopped evolving. As the show wraps its four-season run, the main cast sits down to reminisce.

“It’s pretty ridiculous how subtle we are with the look of our show,” Herse says. “Almost the entire series is shot on one lens, a 27 millimeter focal length, and we like to move the camera in and out to create compositions. For this particular episode, we wanted to feel a little bit of a shift, so we made the incredibly subtle change to shooting most of the episode on a 32 millimeter lens — that’s basically a one-lens increment difference. It has a little bit more of a formal sensibility to it and is a little less comical than the show tends to look. Though we’re showing these big, wide-open landscapes, I wanted to feel a bit of a claustrophobic sense working against that. I was hoping that the specter of Barry and Sally being discovered would hover over the whole thing.”

Reduced camera movement and more static shots created the sense that our paranoid pair were stuck in the middle of nowhere. A sequence in which a knock on the door drives an armed Barry out into the night employed no light except that coming from the house, another stripped-down choice that represented the character’s struggle to face the darkness.

The house’s interiors were filmed on a Sony soundstage. A 360-degree backdrop showed the horizon outside of any window. Times of day were expressed through controlled lighting.

“We never would’ve achieved that eerie dusk scene where Barry’s actually talking about tricky legacies on location,” Herse notes, “because you’d never be able to shoot the entire scene in that one, five-minute window when the sun sets. That took a lot of effort with grip and lighting. We blacked out the back side of that backdrop so there was a clean silhouette line of the landscape. We had something like 100 lights encircling the set that had fiery pink and orange hues, then faded that up into the deep blue dusk. This helps tell the story that Barry is locked into this idea and Sally is totally indifferent, so no one’s turning the lights on to this ever-darkening atmosphere while they’re eating dinner.”

Another side of Barry’s fears comes out when he tries to discourage John from playing baseball with local kids by showing his son videos of boys getting killed on Little League diamonds. Hilarious and alarmingly realistic, they’re a visual element Herse is happy to share credit for.

“Those had to be staged; I don’t think there’s an ethical argument for showing real child fatalities on screen,” he wryly states. “They were primarily choreographed and shot by our stunt coordinator, Wade Allen. We shot them for real on an iPhone, the way a parent shooting a video would do it, just running around with it handheld. The hope was that that would feel like an authentic, found footage piece of sad material.”

Other screens within screens helped advance storytelling: a pullout from a TV preacher to indicate Barry’s newfound, if self-serving, religion; Sally’s suppressed fury watching former colleagues praised for their popular shows, while the part she now plays every day must remain secret; a Warners executive walking past huge soundstages (actually, again, on Sony’s Culver City lot) adorned with video billboards, one promoting the latest sequel to a movie that was in production during the previous episode.

Season 4 of the HBO series spotlights, the actor’s growth as a filmmaker. He and co-creator Alec Berg talk about how he came to trust his own lens.

“That’s the kind of formal approach we tend to take with camera on the show,” Herse says. “We try to fit as much into a single shot as possible. That wide shot takes us across these giant walls where you get all of this near-future technology up there. You see that billboards aren’t static but these bizarre, repeating, TikTok-like videos. You learn that enough time has passed for ‘Mega Girls 4’ to exist. There’s this interesting use of scale with this tiny character played against the giant walls; that was a 200-foot dolly move that we had to set up.”

Overall, Hader brought out Herse’s storytelling skills while the cinematographer contributed to the director-star’s growing reputation as a visually savvy auteur.

“I’ve been looking for a filmmaker like Bill to work with for my entire career,” Herse says. “We both have similar filmmaking idols. Anytime I was asked what kind of project I’d like to work on, I always kind of joked a Coen brothers movie. I know that will never happen, but the tone of ‘Barry,’ to me, is as close as I’ve gotten to that expression of how, within a short period, a person can experience comedy, tragedy, absurdity and existentialism. It’s a very layered experience to be human, and that’s what I love so much about ‘Barry.’ Anyone that reads the slug line for the show — ‘Hitman that wants to be an actor’ — would never anticipate just how much this show touches on in terms of the human experience.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.