Ashes to ashes: What L.A. can learn from San Francisco’s 1906 disaster

- Share via

Well, crap.

No better way to put it. Here we are, with nature and circumstance teamed up for a natural disaster that has left Los Angeles sagging, flattened like an old party balloon, the breath sucker-punched right out of us.

The breath, but not the energy, nor the spirit. We want to be as resilient as one of those bottom-weighted old Joe Palooka toy punching bags that always pops back after a wallop.

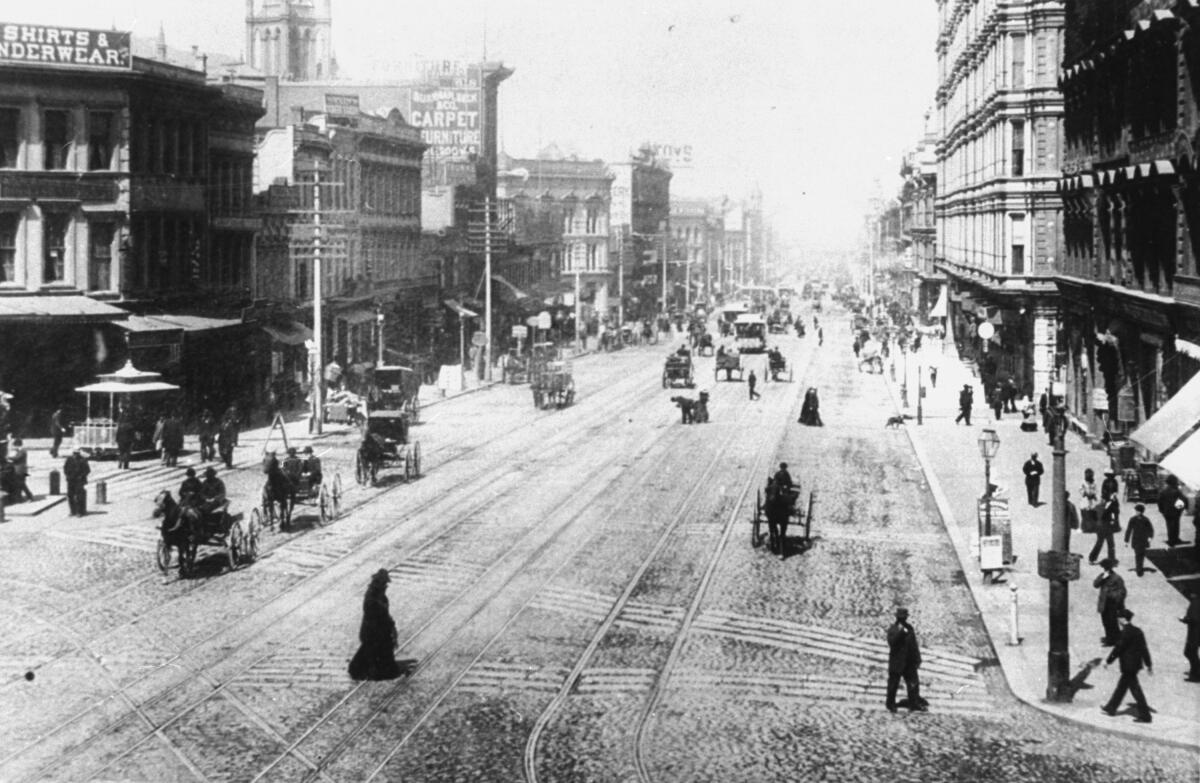

With that in mind, I began to think about our sibling city up the coast, and the near-death experience it had in 1906, the three or four days of fire roaring in on the heels of its earthquake: more than 80% of the city razed, 28,000 buildings and 500 city blocks gone, at least half of its people homeless.

The scale of the damage in Los Angeles’ latest catastrophe is just as stark: Nearly 40,000 acres burned flat and more than 12,000 structures, including many homes, damaged or destroyed.

My old friend Kevin Starr, the great historian of California, was a San Francisco native. He loved and often worked in L.A. but he loved San Francisco, with that particular zeal of people who call that city “the city.”

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And he told me one day, as we were driving across the plain of L.A., that the collapse of California’s premier city, which is what San Francisco was in 1906, had opened up an opportunity gap in our blooming state, and Los Angeles filled that void. It was as if San Francisco was throwing touchdowns until L.A. intercepted, and ran the ball back for its own score — over and over again.

San Francisco’s recovery is a heroic story, and it kept the city’s hands full for years.

But what Kevin told me was that in those years that San Francisco was sidelined, L.A. zipped into the breach, enticing investment and trade to come to California or stay in California — just to do it a few hundred miles to the south.

And so it happened. L.A. took over the lead from San Francisco and never let go.

There’s a solid book by historian Mansel Blackford, “The Lost Dream: Businessmen and City Planning on the Pacific Coast, 1890-1920.” It was written more than 30 years ago, and it’s more engrossing than you’d think from its title. What I learned from it is worth laying out at a bit of length here.

After 1906, Los Angeles merchants “took advantage of the confusion” to “penetrate” — presumably marketing its goods — north into the great Central Valley. When San Francisco’s frustrated businessmen asked the state’s railroad commission to give them a break on rates, to help San Francisco restore its fortunes, the commission — under who knows what influences — instead lowered rates for L.A., and used its business growth as a reason. The head of San Francisco’s Civic League complained in 1911 that the railroad system had essentially become “a large funnel … with its spout at Los Angeles.”

Oakland began enticing port business away from San Francisco, as did Seattle, Portland and L.A. Southern California companies that had prospered locally extended their reach way up north. The Simons Brick Co.’s logo-stamped bricks — still found in old patios and stairs here in L.A., including mine — were shipped to San Francisco by the hundreds of pallets.

L.A. took the lead from San Francisco, then leveraged it to barrel into new businesses: movies, aviation and, of course, oil.

Frances Dinkelspiel is an author and journalist who has written a lot about California, including the book “Towers of Gold,” about her forebear, the pioneering banker and landowner Isaias Hellman. Hellman practically founded the banking business in L.A., bankrolling big civic projects, and then he moved up north in the 1890s, at a moment when, as Dinkelspiel said, San Francisco had more millionaires per capita than anywhere else in the world. Hellman kept his faith and his fortune in San Francisco through its desperate years.

It was a slog, though. “San Francisco was taking a long time to rebuild,” Dinkelspiel told me, “and that’s why San Francisco was so keen on getting the exposition in 1915.” (She was referring to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a kind of world’s fair.)

“They fought really hard for that,” she said. “They were going to show the world that San Francisco had risen like a phoenix from the ashes.” Three buildings survive from the exposition, among them the spectacular Palace of Fine Arts.

In 1936, 30 years after the earthquake and fire, MGM released its prestige film “San Francisco,” starring Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Jeanette MacDonald. At the end of the film, as homeless San Franciscans camp in a park and mourn their dead, a kid runs up hollering, “Fire’s out!” People cheer. They stream out of tents and crest a hill en masse, singing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and gaze down on the smoky ruins of the city. A man among them hollers, “We’ll build a new San Francisco!”

“New” is a curious word choice. Would a “better” San Francisco have implied there was something wrong with the first one? San Francisco had burned often before — five times in two years, right after the gold rush began.

In 1905, scant months before the earthquake, San Francisco had been presented with the Burnham Plan, a park-centric model for an ideal reimagining of the city. The plan was welcomed before the quake but pretty much ignored after — an opportunity lost.

L.A. too once has a forfeited paradise in our past. The Bartholomew-Olmstead plan, commissioned in 1927 by the L.A. Chamber of Commerce, was called “Parks, Playground and Beaches for the Los Angeles Region.” It is a heartbreaker to see, for what might have been: an “emerald necklace” of mountains, rivers, parks and beaches. Present-day L.A. would, had it been adopted, be dramatically different, a more livable, human-scale place. After it was presented to the chamber in 1929, it sank, virtually traceless — too big, maybe, too expensive, too ambitious, too contrarian to the plans of real estate salesmen.

And so L.A. became … this L.A. And what will our next L.A. become after these conflagrations? Will it, like San Francisco, forfeit our world advantage as a powerhouse of the moment and also as a leader in thinking better about big things?

Those answers are still too big for this moment and this space. Before last week, I was already writing a column taking Los Angeles to the woodshed for not being and doing and thinking boldly enough. The moment for that one will come.

Adam Rose, a research professor of public policy and engineering at USC, is an expert in disaster economics, and he noted to me some differences that may be predictive in L.A.’s comeback: San Francisco’s mostly commercial fire damage, versus L.A.’s residential damage; L.A.’s manufacturing base and its big export business remain mostly untouched by the fires. The X factors in the revival, Rose says, will be altogether different ones: infrastructure, drought, climate change and our politics.

Not even hours had passed last week when an exchange of text messages between Gov. Gavin Newsom and President Biden put the full apparatus of federal disaster aid into motion.

Within a few hours, too, on social media, the incoming president, Donald Trump, also had a message for California’s governor “Newscum” and the “virtually apocalyptic” regions that were ablaze. His were not words of sympathy or support. He concocted grievances and falsehoods and accusations against Newsom and the firefighting situation. Newsom, Trump posted, is the one to blame.

In 1903 the vigorous, curious president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, visited California for two weeks. He camped for three nights in Yosemite with naturalist John Muir. He was cheered through the streets of San Francisco. He toured Los Angeles with his Harvard classmate, the ethnologist and writer Charles Lummis, and admired the natural beauty enrobing the city.

Three years later, a couple of weeks after the San Francisco quake, the Republican Roosevelt noted from the White House that help had already been forthcoming from “the Canadian government, with an instant generosity peculiarly pleasant as a proof of the close and friendly ties which knit us to our neighbors of the north … With a generosity equally marked and equally appreciated the Republic of Mexico, our nearest neighbor to the south,” from Guatemala, from the Empress of China, from Japan, and New Zealand, and Martinique, and other nations of the world.

By midday in Washington, D.C., on April 18, 1906, Roosevelt was telegraphing the California governor with unconditional support — a million dollars already coming our way, and the pledge of more: “You will let me know if there is anything that the national government can do,” and the news that the secretary of war had already been ordered “to do everything that you direct that it is in our power to do.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.