A beloved Beverly Hills burger joint mysteriously closed 27 years ago. What happened?

It’s a kinda-sorta memory. About the char of a cheeseburger from my childhood. I can almost taste it.

It came to mind during a terrible stretch for the Los Angeles restaurant industry.

More than 65 notable eateries closed last year, and the trend hasn’t let up: Spartina, Manzke, Pearl River Deli and others shuttered in the first few months of 2024. It seems harder than ever to run a successful restaurant, amid the rising cost of ingredients, labor, rent and utilities.

The bleak news got me thinking about the first eatery whose closure left me bereft. Jeremiah P. Throckmorton Grille — a casual spot in Beverly Hills — was a real-life “Peach Pit” that for years served devotees burgers, hot dogs and egg creams, until it shut down suddenly in 1997.

For many, Throckmorton — or Throck’s, as regulars called it — offered a taste of adolescent freedom: You could walk there after middle school and order a burger, fries and a milkshake, without anyone saying it’d spoil dinner. Sitting at the long counter, you hatched plans with friends. You worried about a math test. And you savored your independence.

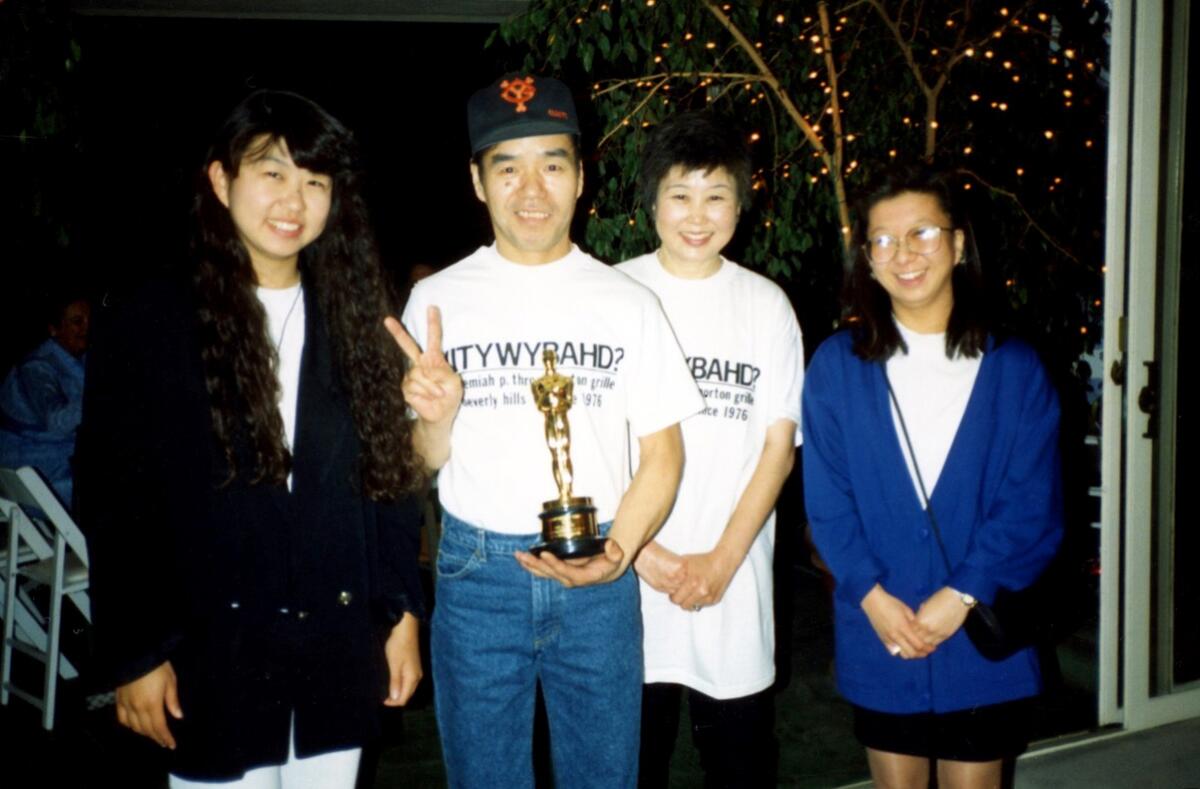

The South Beverly Drive restaurant had its quirks. There was the peculiar name, which conjured visions of a fusty baron. Then there was the inscrutable acronym — IITYWYBAHD? — emblazoned on workers’ shirts. Knowing its meaning was like a secret handshake. But the most interesting thing about Throck’s was its owner: Sadao Nagumo.

An enigma in an apron, he was generous with his wide smile but not with conversation. Still, the Japanese immigrant conveyed his affection with a fake bottle of ketchup he’d squeeze at diners. The unsuspecting would recoil — then dissolve in laughter when they realized they’d been hit with red string.

His burgers were basic, but among adherents, polishing one off as Nagumo looked on was something close to communion.

“I have been chasing that burger and that feeling for the rest of my adult life — and just have never found it,” said former “All My Children” star Matt Borlenghi, who started going to Throck’s around 1980. “It felt like home when I was there. I’ve pretty much given up ... on trying to find another Throckmorton.”

It was clear how much Throck’s meant to people. On more than one occasion, when an interviewee for this piece paused for an extra beat, I wondered if he was crying — or at least trying not to. But the restaurant’s story seemed clouded with questions. Who was Jeremiah P. Throckmorton? What was the source of that acronym? And, most important, why had the place closed with no warning?

Throckmorton’s shuttering occurred in the era before the internet conferred immortality to even the humblest of establishments. Unlike today, when closures are announced with heartfelt social media posts, restaurants used to shut down quietly. Then as now, the rare ones that coalesce into beloved gathering spots can leave holes in a community that linger for years. For a generation of kids from Beverly Hills, that spot was a simple diner run by a humble man of few words at a grill.

Tracing the arc of the man behind a treasure map revealed a story that entangled a forgotten film star, an “Andy Griffith Show’’ obsessive and other intriguing characters.

After Throck’s closed, my teenage friends and I were dismayed. Without any solid information, we spun wild theories about the shuttering.

Twenty-seven years later, I decided to find out what had actually happened.

The restaurant, I soon learned, was founded by March Schwartz, the late publisher of the Beverly Hills Courier. Two of his sons filled in some of the history. Jef E. Schwartz said that he also recalled Throck’s closing mysteriously — and that even his father, a city insider, was in the dark.

‘Would you buy a hot dog?’

March Schwartz loved to spin a story. He loved food too. His passions collided at Throckmorton, which he opened in spring 1976 on Little Santa Monica Boulevard, a brief Times story announced.

I’d heard that the restaurant’s name could be traced to a figure in a Charles Dickens or H.G. Wells story. But Sande Schwartz, another of the publisher’s sons, understood Jeremiah P. Throckmorton to be the name of a character his father had invented. There is, however, another with the name: A character who appeared in 1994’s “Red Skelton: Bloopers, Blunders and Ad-Libs” was called Jeremiah P. Throckmorton.

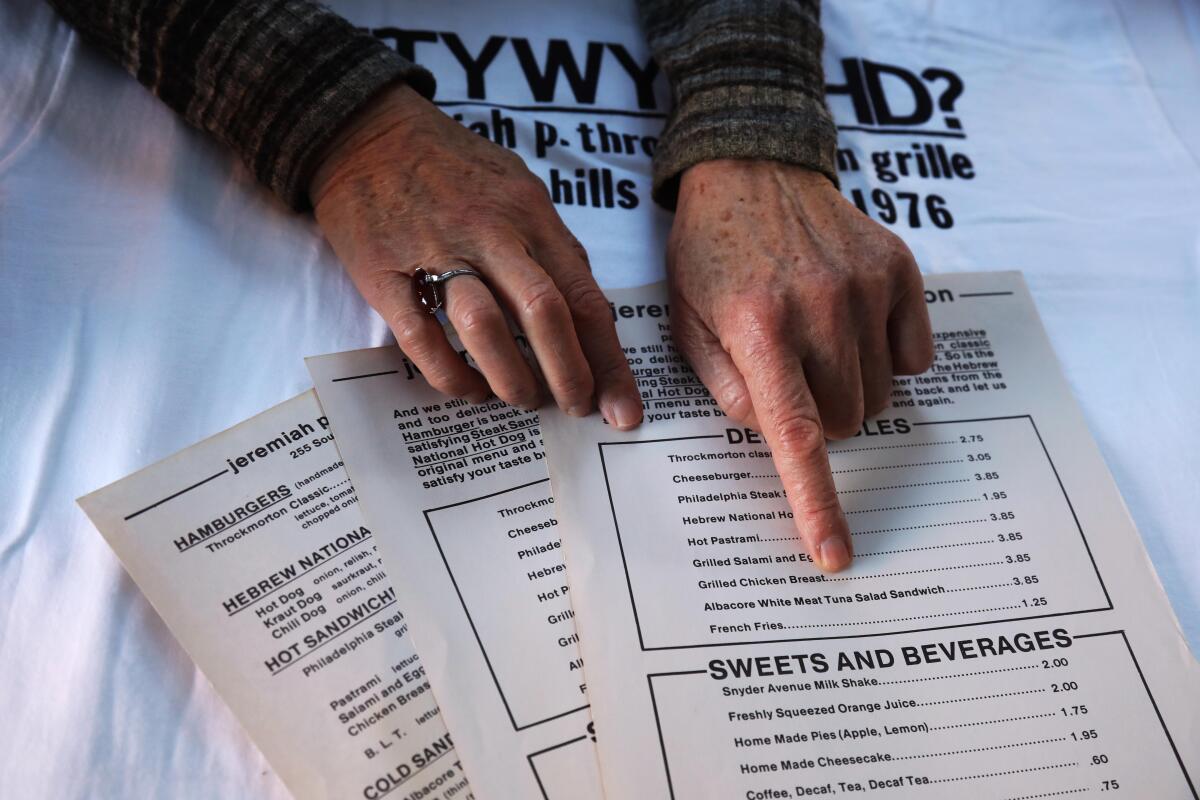

Jef said the restaurant’s IITYWYBAHD? slogan — it stood for “if I tell you, would you buy a hot dog?” — also sprung from his dad’s imaginative mind. The line, he explained, was a joke: “You’d get people to ask you what it is, and then you could sell them.”

Beverly Hills Car Club and co-owner Alex Manos have built a following, but lawsuits accuse the dealership of selling vehicles with undisclosed damage, defective parts or other issues.

Within a year, Schwartz put the restaurant up for sale. This was how Nagumo came to own it. But there was little on the internet about the man — besides an obituary. Nagumo died at 78 in 2016.

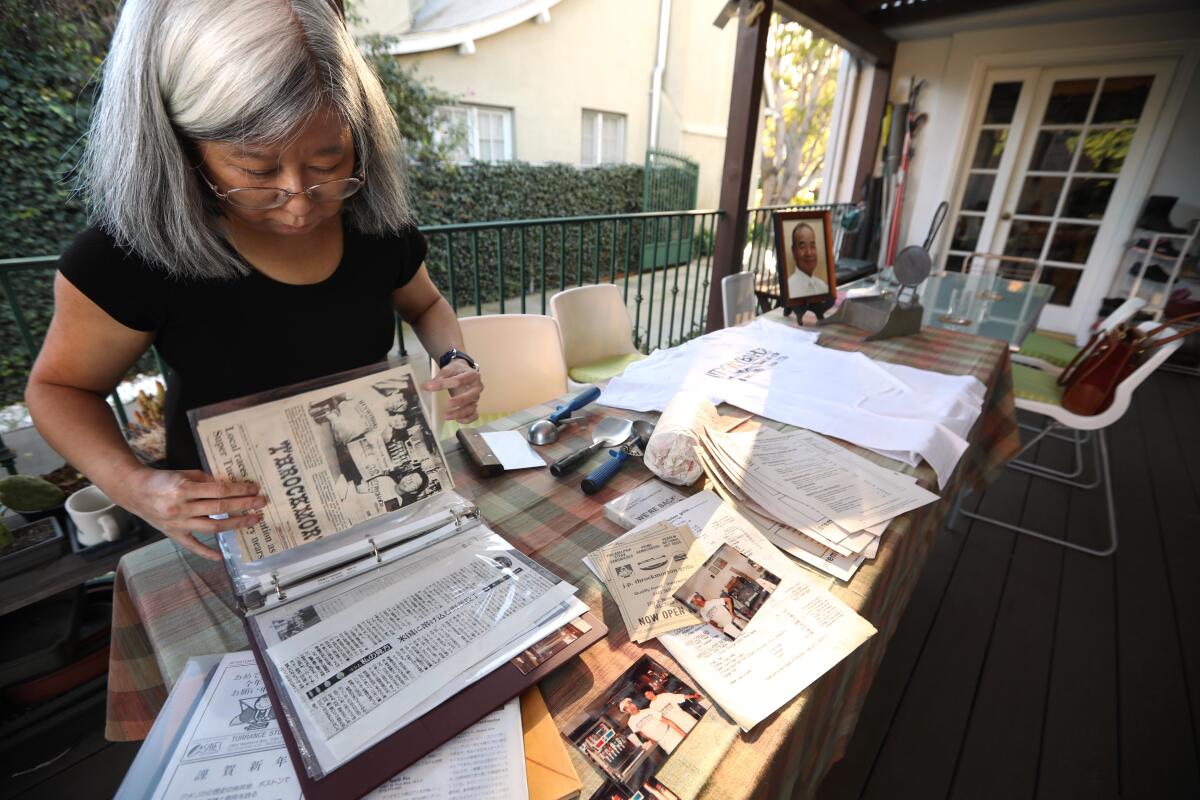

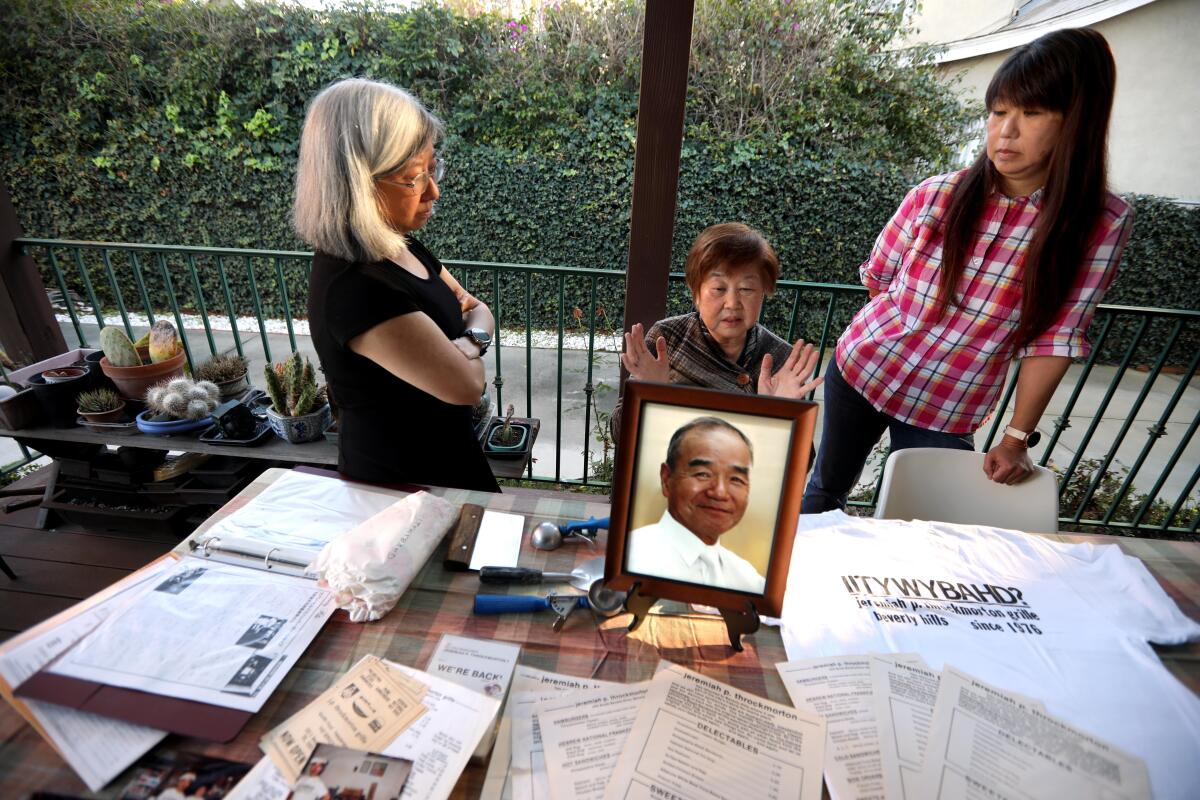

“He served his customers with diligence, honesty and humor until 1997,” the notice said, noting that Nagumo was survived by his wife and two daughters. They agreed to meet with me.

We convened at the Beverly Hills home of Nagumo’s widow, Atsuko, who told the story of Throck’s alongside daughters Takako and Nori.

In 1975, the Nagumos, who hailed from Tokyo, visited the U.S. on a six-month holiday. When they returned to L.A. a year later — this time with designs on an even longer stay — they learned that buying a local business could help them secure green cards. They scoured Times classified advertisements for restaurants.

They had no experience in the business — Sadao’s family owned a Tokyo pachinko parlor — but figured it would be easier to master than other trades.

An ad for Throck’s caught Atsuko’s eye because it mentioned Beverly Hills. So the family checked out the restaurant in December 1976.

They didn’t know much about hamburgers. But even with their limited English, Sadao and his wife grasped the essence of Schwartz’s spiel: “This is a place where you make the hamburger patties every day, fresh,” he told them, according to Atsuko, 80.

The Nagumos struck a deal to buy Throckmorton and set out to learn the restaurant business.

This was decades before Father’s Office put caramelized onions, blue cheese and arugula on its burger, and the one at Throck’s was a mostly traditional affair. It came with shredded lettuce, tomatoes, pickles, relish, chopped onions, mustard and mayonnaise. My order: Hold the relish, easy on the mayo.

Regular Rick Schwartz liked the burger, but for him, it was all about the steak sandwich — with onions.

“It was really the first time I started to have a relationship with onions — we never knew each other until Throck’s,” said Schwartz, who is not related to the restaurant’s founder. “They say when you get bar mitzvahed, you become a man, but I think you’re not a man until you learn to like onions.”

Throck’s became a beloved neighborhood spot. It attracted Hollywood types such as Elton John and Bette Midler, the Nagumos said. And there were the kids who went on to achieve fame — including Borlenghi.

“I used to talk to Sadao about wanting to be an actor,” said Borlenghi, whose recent work includes “Cobra Kai” on Netflix. “I really would’ve been proud for him to see me on ‘Cobra Kai.’ I’d love to be able to walk in and talk to him about that.”

The heir

After more than 10 years at its original location, Throck’s moved to South Beverly Drive around 1989. This was the version of the restaurant that I’d known.

The Nagumo daughters worked there alongside their parents when their schedules permitted. Nori manned the fry station, Takako took orders, Sadao tabulated checks, and Atsuko dressed the burgers as they came off the flat -top grill.

“You could always see the bond with his family — and what his family meant to him,” Borlenghi said.

But family ties were what led to the restaurant’s closure.

Sadao’s father was diagnosed with cancer in 1997. It was then that Sadao made a decision — one wrapped up in a sense of duty. In coming to America years earlier, he had forsaken his birthright: As the oldest son among five children, he was in line to inherit the pachinko business.

“There was a lot of hope for him: This is the child that is going to take over,” Atsuko said. “But he couldn’t.”

The Nagumos stayed in L.A. much longer than anticipated — and it was time for Sadao to return to Japan.

“I need to go back home and take care of him,” he told his wife.

He asked Atsuko to permanently close Throck’s. She offered to keep it open, but he felt he had to be there himself.

Sadao left for Tokyo, where he stayed until his dad died. He was gone for about six months.

Celebrity chef Matthew Kenney, who once boasted an empire of dozens of restaurants worldwide, has closed at least 12 spots since 2022 while fending off lawsuits.

Within days of his departure, the restaurant closed. Takako said they put a sign in the window explaining the shuttering, but I — and apparently others — missed it. For younger patrons, the closure meant the loss of a kind of father figure.

Throck’s had lasted 21 years. By the time Sadao died in 2016, it’d been gone for nearly as long.

“I regret that I never got to take my kids to have a burger there, but I did take them to his funeral,” Borlenghi said. “I was honored to be able to say goodbye. He had opened his heart to us for decades.”

In interviews, patrons took pains to articulate precisely why the place meant so much to them. It came down to a feeling.

“Never was there a man who meant so much who said so little to all the kids of Beverly Hills,” said Steven Fenton, another regular. “There was this understood love of cheeseburgers, back and forth, between myself and Sadao.”

The Throckmorton way

A Japanese restaurant inhabits the space that once was home to Throck’s. Sushi Kiyono has been there for 26 years, making it a rare small-business stalwart on Beverly Drive, which is glutted with chain restaurants such as Jimmy John’s and Chipotle.

Throck’s, Rick Schwartz said, “represented a very different time in Beverly Hills.”

“I guess people’s haunts eventually all fade away,” he added. “But there was something about sitting at that counter.”

The interview with the Nagumos wound down. I made a move wrap things up, but Atsuko had a question: Did I want a cheeseburger, made the Throckmorton way?

I hadn’t counted on this. Moments later, she brought out a burger, with apologies. The lettuce wasn’t shredded. And she’d run out of pickles. But it was wrapped in paper, just like it had been at Throck’s.

I took a bite.

It didn’t taste like the burger from Throck’s. How could it? Nothing can compete with nostalgia.

But it was delicious.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.