Hepatitis A scare at Men’s Central Jail led to more than 1,500 vaccinations

More than 1,500 people were vaccinated last year after an ailing inmate worker at Men’s Central Jail unwittingly exposed thousands of detainees to hepatitis A before medical staff discovered what was wrong with him, according to a report released this week by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the time, Los Angeles County officials said no one else caught the virus, and the CDC report attributed the successful containment to the county’s quick response. Within 48 hours of detecting the highly contagious virus, officials identified nearly 6,000 people the infected man had potentially come into contact with and offered free vaccinations to more than 2,500 of them.

“This exposure response highlights the importance of initiating a rapid response to hepatitis A exposure in a jail setting to minimize risk for transmission and help prevent an outbreak,” said the report, written by several members of the Los Angeles jail’s medical staff.

In a statement Thursday, the county Sheriff’s Department emphasized that jail officials worked with medical staff members to make widespread vaccinations possible.

“The health and safety of our entire incarcerated population as well as our custody personnel is very important to us,” the statement said.

The county’s Correctional Health Services did not immediately offer comment.

Because of the communal living and crowded conditions, jails and prisons are typically high-risk environments for infectious diseases, including COVID-19, influenza and hepatitis A. Even outside of jails, health officials say, hepatitis A outbreaks have been increasing in recent years — especially among men who have sex with men, people who use drugs and people experiencing homelessness.

As Jay D. Aronson and Dr. Roger A. Mitchell explore in their recent book ‘Death in Custody,’ that lack of data is a national problem.

The man who fell ill in Men’s Central Jail was initially incarcerated on April 27. He reported a history of injection drug use and homelessness and said he was in withdrawal from alcohol, according to the CDC report.

Nearly a month later, on May 25, he visited the jail clinic and told the medical staff he’d been vomiting for two days. They gave him nausea medication and antacids, and he reported feeling better later that day, according to the report. But over the next three days, he got worse. When he saw medical staff again on May 28, he appeared jaundiced and said he hadn’t eaten in four days because of stomach pain, nausea and vomiting — all symptoms of hepatitis A. He was sent to a hospital for emergency evaluation, and testing soon confirmed his infection.

On May 30, public health officials told the jail about the test results and determined he may have been infectious as early as May 9. Because the incubation period for hepatitis A is so long — 15 to 50 days — it was unclear whether he caught the virus in jail or before his arrest, according to the report.

Though officials immediately began identifying whom he may have been in contact with in his housing area, it wasn’t until May 31 that the Acute Communicable Disease Control branch of the county Department of Public Health interviewed the man and learned that he’d been an inmate worker assigned to meal preparation in the jail kitchen.

Once county health officials relayed that to jail medical staff members, they expanded the list of possible contacts to account for his jail job.

The state board that inspects jails is asking the L.A. County sheriff to address their concerns at a February meeting.

By June 1, officials launched a mass vaccination campaign, starting with the people who had been housed with the infected man. Over the next two days, they offered the vaccine to other kitchen workers and eventually to anyone who’d been in Men’s Central Jail during the infectious period.

In total, officials identified 5,830 people who had been housed in the jail during that time frame, 4,128 of whom were still incarcerated. Of those,1,362 had been vaccinated or had the virus previously. By June 12, officials offered vaccinations to the remaining 2,766 people, nearly 55% of whom accepted them. Kitchen workers who refused and had not previously been vaccinated were reassigned until the end of the incubation period.

Jail employees and medical staff were notified about the possible exposure and offered vaccines. And though officials said last year that the timing of the incubation period coincided with a large group tour that included a federal judge, U.S. Department of Justice officials and attorneys with the American Civil Liberties Union, leaders in the Sheriff’s Department said they did not believe the visitors had been exposed.

“They did not visit the housing area involved, nor did they eat any food,” Assistant Sheriff Sergio Aloma said at the time.

As of October, no additional cases of hepatitis A had been reported or identified in any of the county’s jails.

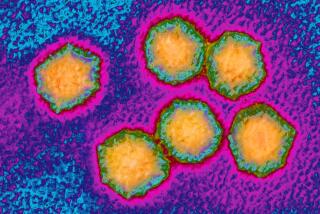

Hepatitis A is highly contagious, and people can spread it before they feel sick, according to the county Department of Public Health. The virus causes a short-term liver infection and is found in the stool and blood of infected individuals. It’s usually transmitted by eating contaminated food or through close contact with someone who is infectious.

The trove of jail security footage was released after The Times and Witness LA asked a federal judge to make the videos public.

There is no specific antiviral therapy for the infection, which is part of why officials focused on a mass vaccination campaign instead.

This isn’t the first time that Los Angeles jail officials have rapidly vaccinated large numbers of people for hepatitis A, according to Thursday’s the report. From 2007 to 2010, the Los Angeles jails had several hepatitis vaccination campaigns targeting gay men, and from 2017 to 2019 jail officials offered vaccines to the entire population after a hepatitis A outbreak in San Diego.

This time around, improvements in electronic health records made it easier for officials to identify people who had been vaccinated and focus outreach efforts on those who didn’t have any immunity. The report said that because jails present “a unique opportunity to reduce hepatitis A transmission and disease through vaccination,” Correctional Health Services “might consider a more comprehensive routine vaccination strategy, including offering vaccination at intake.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.