Individually, each of these five red flags doesn’t usually mean there is avalanche danger, Keating said. But when observed in multiples, the risk has increased, and discretion is called for.

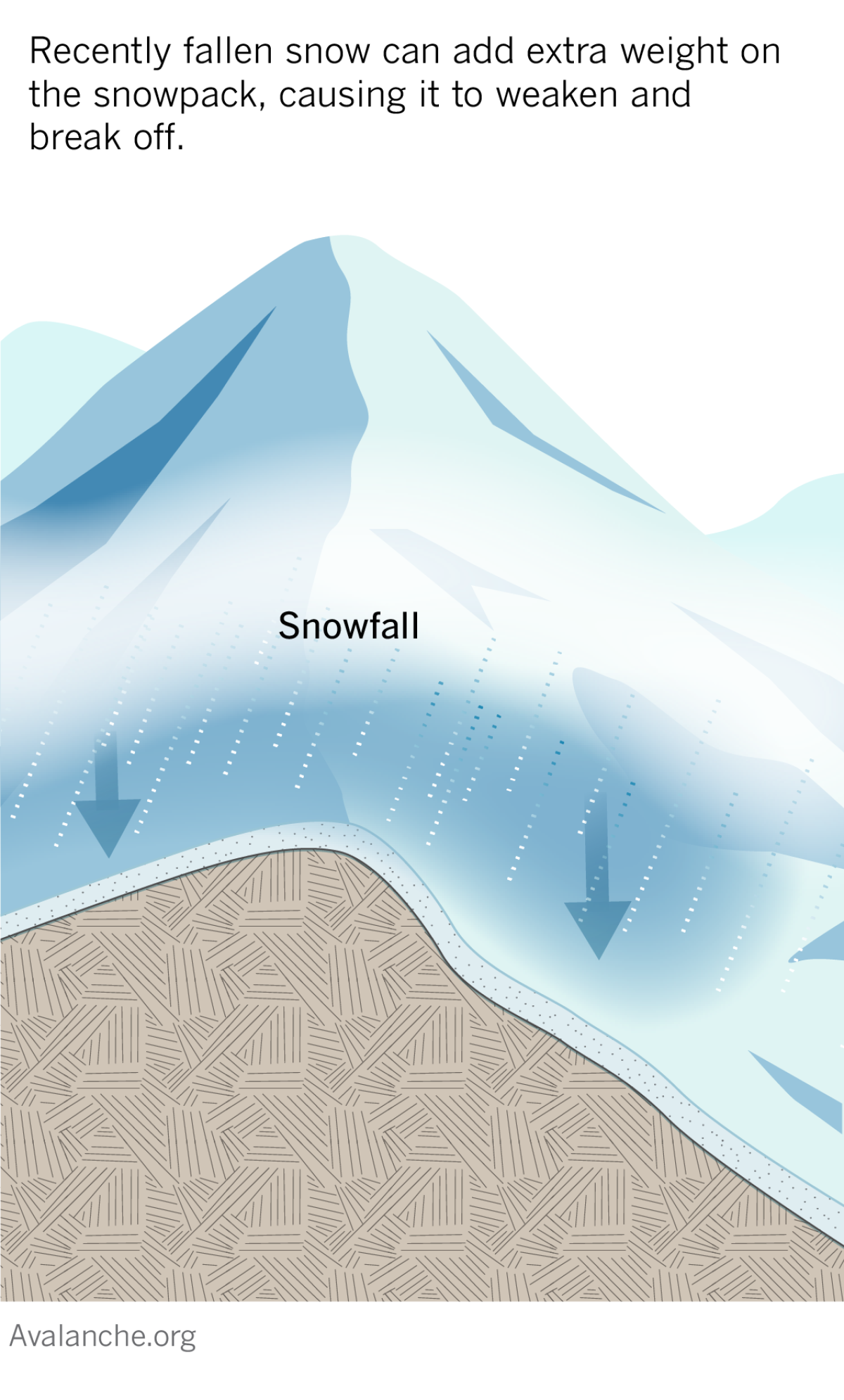

Rapid snowfall: There’s no scientific formula, but Caleb Burns, co-owner of SWS Mountain Guides, suggests that any significant snowfall in a short amount of time can be a red flag.

“If we’re looking at 10 inches in a day, 20 inches in a day — that’s a lot,” he said.

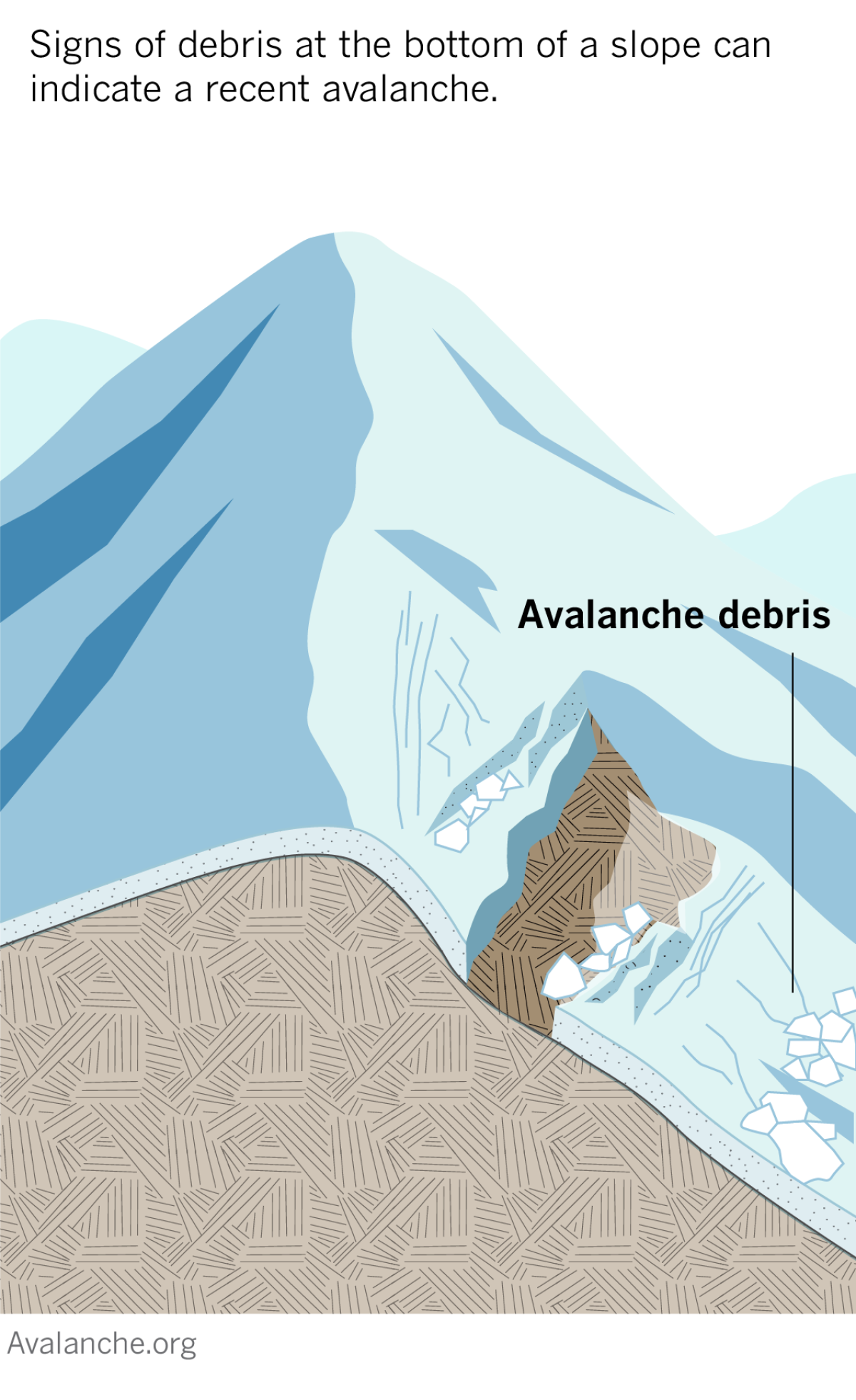

Signs of recent avalanches: Burns referred to avalanches as a “herd species.”

“If you see signs of an avalanche, there are probably more to come,” he said.

They may not be obvious to an untrained eye, but an old avalanche can look like “a still photo of a waterfall” or a mudslide that’s been painted white, he said.

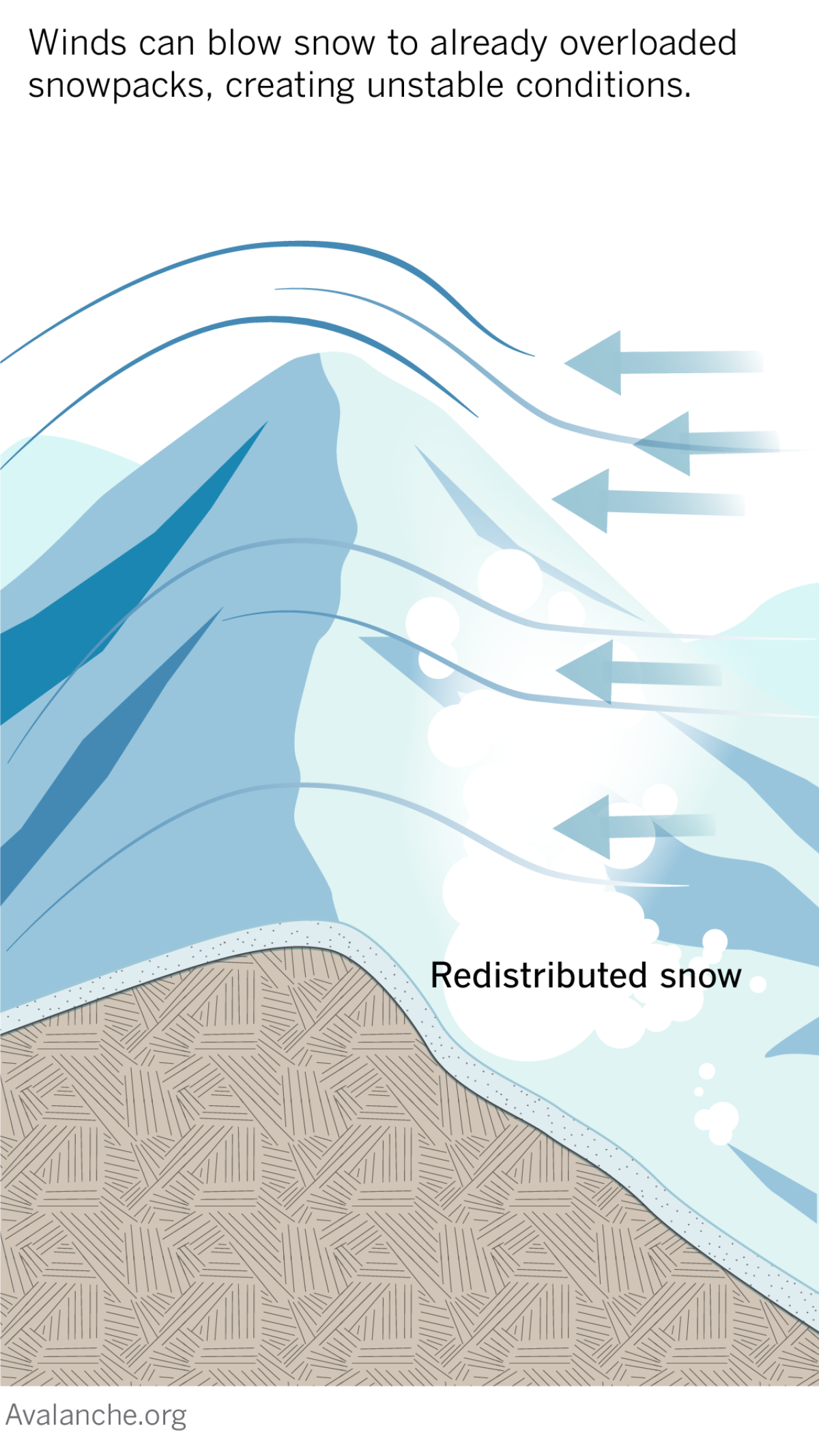

Strong winds: These can move and shift snow easily, Burns said, and pile up a thicker layer of weak snow in areas.

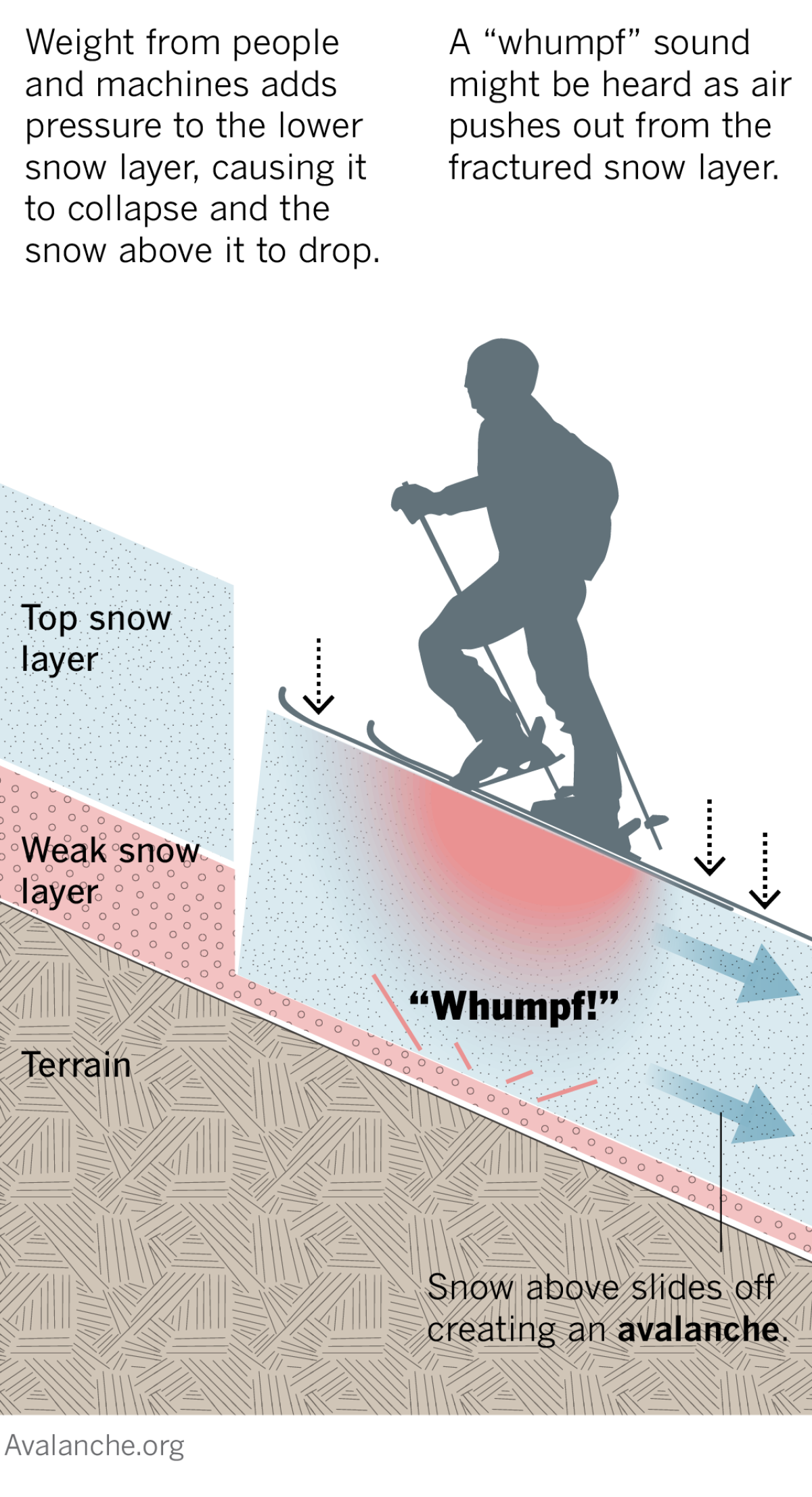

“Whumpfing”: This is the sound that can be heard when snow begins to collapse, showing cracks next to snowshoes or skis.

The sound is made when air escapes through the snow because of the crack, Burns said. It’s common to see small cracks when you’re walking or treading new snow, “but if a crack runs 10 feet away from you, that’s not normal,” he said. “It’s a sign of instability. The snowpack is not happy, and something is going on.”

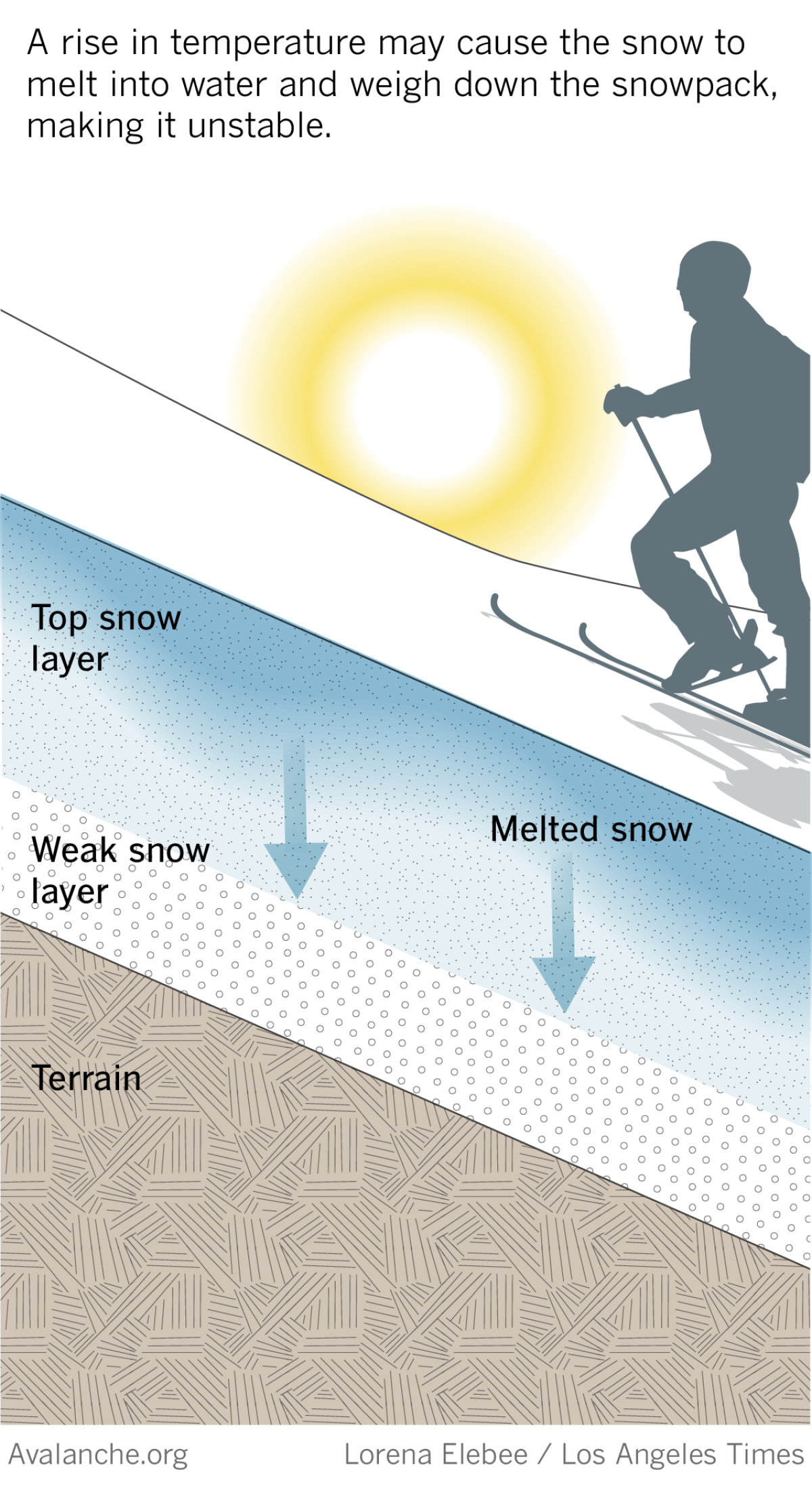

Rapid warming: Sunny skies after a storm that dumps several inches of snow can be welcome but could also be concerning, Burns said.

Rapid, significant warming after a cold start can make snow less stable.

“If you go in the morning and you have your layers [of clothing], and then midday you’re down to a T-shirt, then the snowpack is changing,” he said.