Newsletter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Jason Allen Lee / For The Times

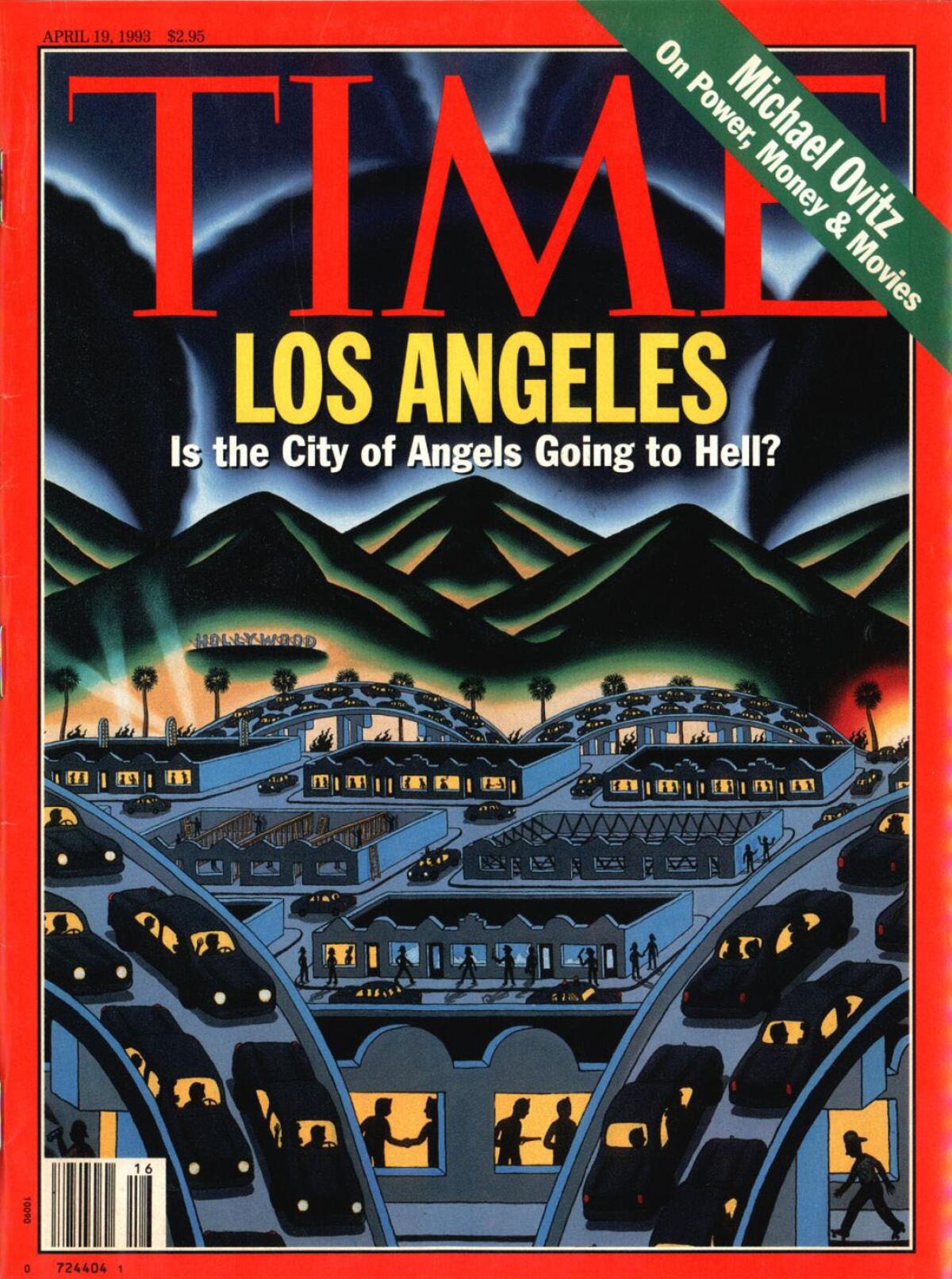

The freeways are clogged with cars. Criminals point guns at the unsuspecting. A fire burns near shadowed foothills.

The April 19, 1993, cover of Time magazine depicts a dark vision of Los Angeles. And the question it asks is even more ominous:

“Is the City of Angels Going to Hell?”

The accompanying story, titled “Unhealed Wounds,” is a portrait of a divided city in the wake of the 1992 riots sparked by the acquittal of the Los Angeles Police Department officers who had beaten Rodney King. The piece paints a bleak picture: the collapse of the local aerospace industry had wiped out tens of thousands of jobs, an initial effort to rebuild after the violence of the prior year had sputtered, and there was a tense race underway to replace longtime Mayor Tom Bradley.

“Much of what seemed modern and alluring about Los Angeles now seems terribly shortsighted and ugly,” the story said. “The ethnic patchwork appears to be a map of bunkered enclaves. Its center cannot hold because the city doesn’t have one.”

The story points to a few bright spots, such as the work of Homeboy Tortillas, a program of Homeboy Industries, which works to rehabilitate ex-gang members. But the magazine mostly looked ahead with angst: the second trial over the King beating had yet to conclude, and its outcome, the story said, would “determine just how much anger is pent up in the city’s poor districts.”

(A companion piece focused on the then-ongoing follow-up trial for the officers who brutalized King. Guilty verdicts were later handed down in the federal case.)

A lot has changed in 30 years.

There are new rail lines, museums and stadiums, and renewal in downtown’s Historic Core and Arts District. Those identifying as Latino or Hispanic now make up nearly half of L.A.’s population. A space shuttle paraded through the streets, the Lakers racked up six championships and the Dodgers won a World Series.

Yet there’s still a sense that L.A. is teetering on the edge.

Soaring income inequality and a housing crisis have widened the gulfs between classes. Climate change has brought on searing heat and megastorms that disrupt daily life and claim lives. Smash-and-grab and follow-home robberies have contributed to a feeling of lawlessness. Outrage over police brutality prompted the widespread social justice protests of 2020.

Read our full coverage of the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots.

And the homeless epidemic continues to spiral: the 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count estimated that more than 75,000 people experience homelessness in the county on any given night.

The question posed by Time was a provocative one. Is this hell?

To find out, we asked 17 prominent Angelenos to weigh in.

There was consensus that this is a fraught time for Los Angeles — nearly every participant mentioned the scourge of homelessness when contemplating the issues affecting the city. That’s in stark contrast to the 1993 Time story: homelessness wasn’t mentioned. Even once.

Chief executive of Union Rescue Mission, a Skid Row-based, privately-funded provider of homeless services

Homelessness is absolutely the biggest issue Los Angeles faces. Homelessness was increasing, unaddressed, right in front of our eyes in the 1990s and no infrastructure was being set up. We were too late to the game to address it in the way that was needed. We never kept up — and then we were surrounded by a tsunami of people suffering on the streets. They are certainly living in a hell on earth.

Homelessness is hell.

— Rev. Andy J. Bales, chief executive of Union Rescue Mission

For the six people who die per day in L.A. County from complications of homelessness, it has been hell. For the family members who have lost their loved ones to the streets, it’s been hell. Homelessness is hell. There is no suffering like hoping the sun comes up so that you don’t shiver anymore, or hoping that you can find a restroom before you get a urinary tract infection. We have really let people down, and we can do so much better.

We certainly won’t solve it the way we are going, with very expensive units for a few, and tens of thousands still on the streets. We need immediate shelters for everybody on the streets and innovative affordable housing. The city is not stepping up to do enough. There is still a chance to turn things around. But we are not going to get there the way we are going about it.

UCLA professor, Nickoll Family Endowed Chair in History, specializing in race and gender studies

In 2020, when we saw the protests around the killing of Breonna Taylor and others, one of the things that was more positive was that people of many backgrounds participated. It wasn’t just Black Lives Matter; it was people of all ethnicities, races and classes. The people who were protesting were more peaceful, as compared to the uprising of 1992. Still, I think most people of color remain wary of the police. This is not just an L.A. problem — this is a national problem.

Are we living in hell?

A reader may find that one topic or another was not covered by the respondents. That’s where you come in: leave a comment below with your take on the question.

When we look at the Black population in Los Angeles 30 years later, we still see a very large and disproportionate number of people incarcerated. The largest proportion of unhoused people are Black. You also see the policing problems, with more Black people — and people of color in general — being stopped and frisked by the police.

I am always hopeful for improvement in L.A. — and I do think it is in a better place than it was in 1993. There are still things we are struggling with: homelessness is the most devastating social problem we have in Los Angeles. But I train students at UCLA — the best and the brightest in Los Angeles — and that’s a hopeful place.

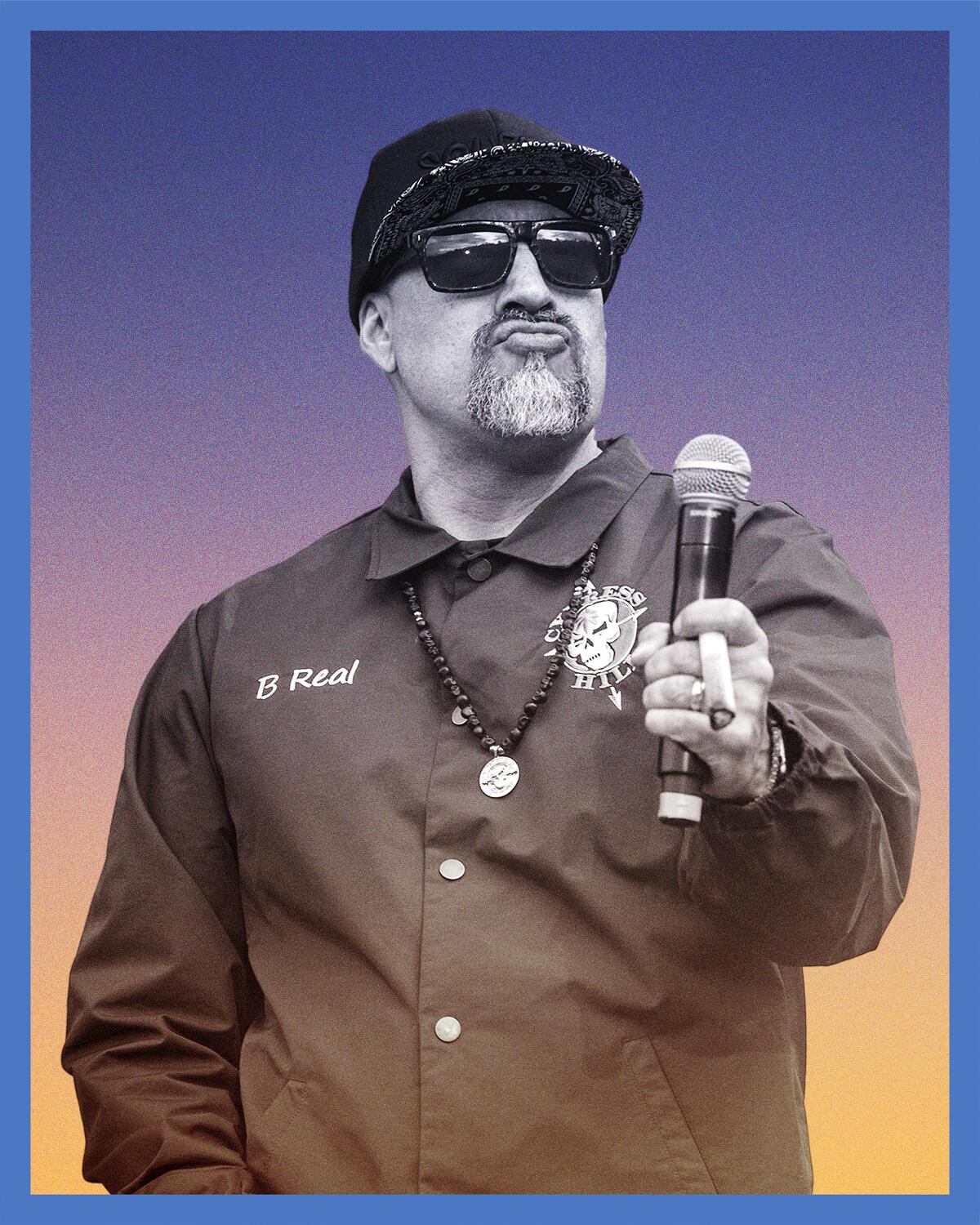

Rapper, founding member of hip-hop group Cypress Hill

I remember coming back from a Cypress Hill show in Humboldt County when the riots had just started — I was living in Venice at the time — and we were seeing smoke clouds everywhere. it was almost apocalyptic. They lost control of the city, from the authorities to the people who lived within it.

Growing up in L.A., you know about the problems. Like being profiled by the Los Angeles Police Department because of how you look and where you’re from. You didn’t have to be a gangbanger to get that kind of treatment.

With hip-hop, a lot of us were talking about things we experienced growing up in L.A. Music became a platform to speak about what we went through. We became voices for people in those communities. It also gave those outside the community an understanding of what it was really like. We found allies who understood what we were going through instead of judging us. Songs throughout our catalog — “How I Could Just Kill a Man,” “Throw Your Set in the Air” and “Illusions” — included significant messages that related to the communities we came from and how we were treated. Because of music I found a way out of gang activities. Hip-hop was taking youth and giving them an opportunity to be something other than a drug dealer or gangster. Essentially, it saved our lives.

Los Angeles is beautiful — and it’s dangerous. Today, it feels more dangerous than it was back then. Gangs and drug dealers have gotten smarter. Technology has helped them do what they do in stealth. And we still have social injustice, police brutality and a lack of opportunities for people. If you’re keeping it real, you are going to talk about the ugly things. Because that’s life. But we can make it better. For things to change, people will need to wake up and not be in denial about what happens here.

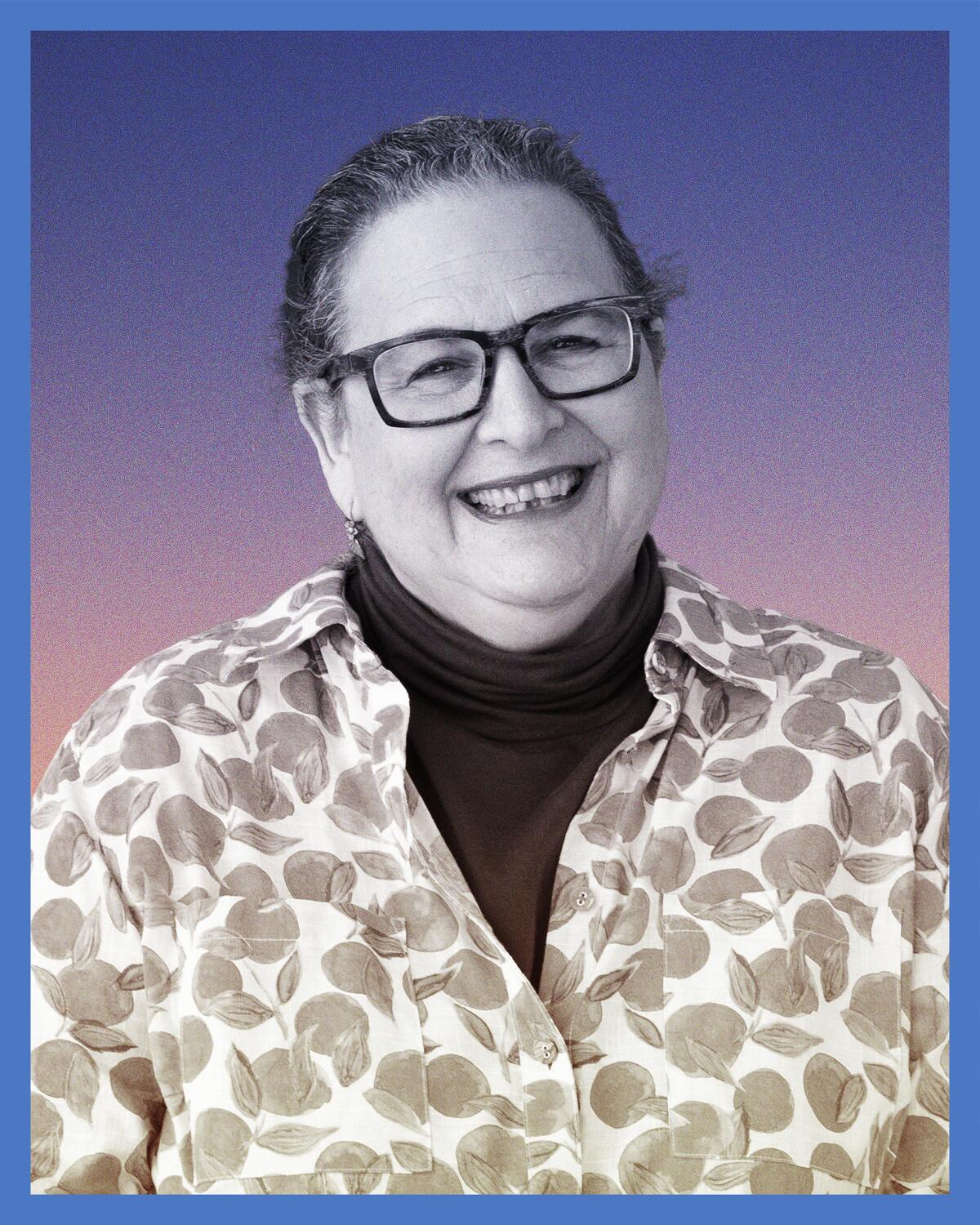

Chef and co-founder of Mundo Hospitality Group, whose restaurants include Border Grill and Socalo

L.A.’s biggest issue is homelessness — it undoubtedly causes the most daily angst. But I am proud to be an Angeleno — and there is still something very positive about our city. In my industry, restaurants are more diverse and exciting than at any point since I moved here 43 years ago. We continue to find ways to delight guests with a variety of cuisines at a variety of price points.

And change is coming — the food-service industry needs to come together and help consumers understand they are eating food that is artificially priced and often made by immigrants, single moms and people of color who work two jobs to survive. It isn’t fair and it isn’t sustainable. I’m glad restaurant workers are demanding more — and living wages for low-wage workers are improving. When communities decide everybody must be paid a living wage, it makes it easier, because then the prices all go up and consumers understand: OK, now it costs more.

In 2020, eight women restaurant operators/chefs and I started a nonprofit called Regarding Her — and over 60% of our 750 members are women entrepreneurs of color. I am proud of the ways we’ve been able to bring our historically siloed community together in three short years.

I am always going to find the silver linings. I love L.A. — I don’t think it’s gone to hell.

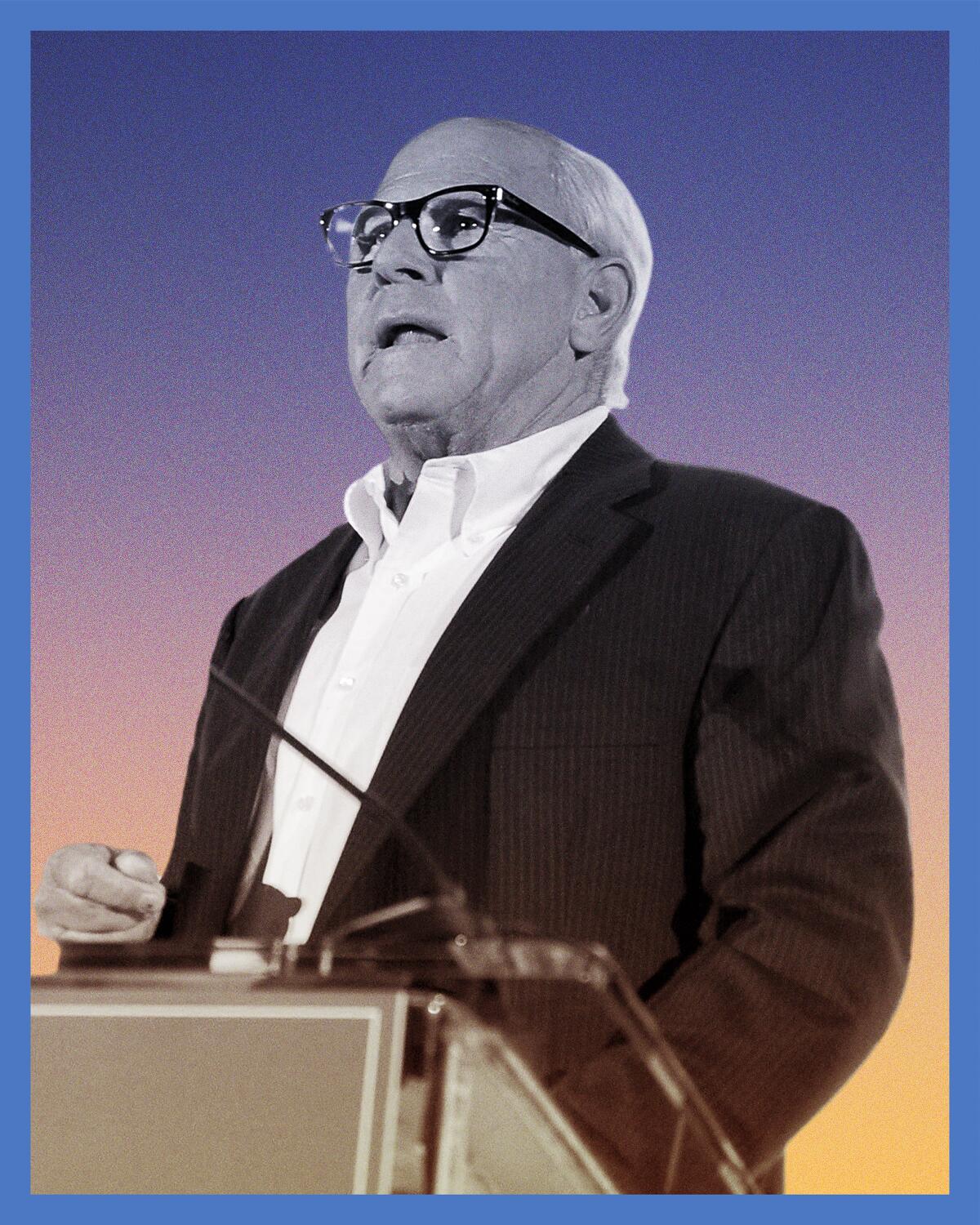

Former chief of the Los Angeles Police Department and a Los Angeles City Councilman from 2003 to 2015

In terms of local politics, local government and the City Council, we may not be in hell but we are close enough to it to where you can feel the heat and smell the smoke. There are many things that are broken. The corruption is overwhelming in society. You have multiple investigations and indictments of elected officials at every level. Many law enforcement officials are being investigated, disciplined for serious misconduct or imprisoned. L.A.’s Ethics Commission, which was established to monitor and investigate the actions of public officials, is dysfunctional, as it is too dependent on elected officials for funding and operational policies.

Our redistricting processes have been manipulated by the city council for self-serving reasons and fail to fairly represent constituents. Recently, three City Council members and a union head showed that they had not learned from prior redistricting mistakes. They too, tried to cut the boundary lines to their liking, while expressing an extreme dislike and thoughtlessness for the ethnic diversity that makes this city great. And, it was all caught on tape. Now, the state’s attorney general is investigating Los Angeles’ redistricting process. We used to think that corrupt redistricting was only done in the South — places where they had to have the Department of Justice keep an eye on things.

You compound the troubles in politics with the corruption at our universities, nonprofits, corporate offices, banking institutions and government work forces, and it’s very clear we are not going in the right direction. And there is little that gives you the sense that there are a large number of people in positions of authority looking to go in a different direction.

Film director, writer and composer behind the “Halloween” franchise and many other movies, including 1996’s “Escape From L.A.”

I fell in love with L.A. when I came here in 1968. I would go to the movies downtown. Oh God, I loved the old theaters down there. I’ve been in love with the city ever since.

“Escape From L.A.” was a movie made with enormous love for the city. We were this nihilistic, dark look at L.A., and the lead character shut the power off on everything with an electromagnetic pulse. A nuclear weapon detonated 25 miles above L.A. would do that — a nuclear physicist told me that. The movie was set in 2013: that’s the problem with doing a near-future dystopian film. It’s going to catch up with you.

These days, homelessness really concerns me a great deal. The housing is way too expensive. We have mountainsides that are crumbling. We have water problems — the droughts. There’s corruption in the government. There are always going to be traffic issues here. I’m having a hard time believing they’ve got the 10 Freeway repaired so quickly. I’m waiting. And the earthquakes — we live on the edge. It makes us feel special about ourselves. It’s ridiculous because at any moment we could topple over — topple over into doom. That’s L.A. for you — there’s nothing like it.

We do have problems, but they don’t rise to the level of hell. The weather is nice — this is our winter. If you read the papers, they say a lot of the population is leaving California. Well, I say, “Bye! Take off.” We need more room here. It’s always been crowded.

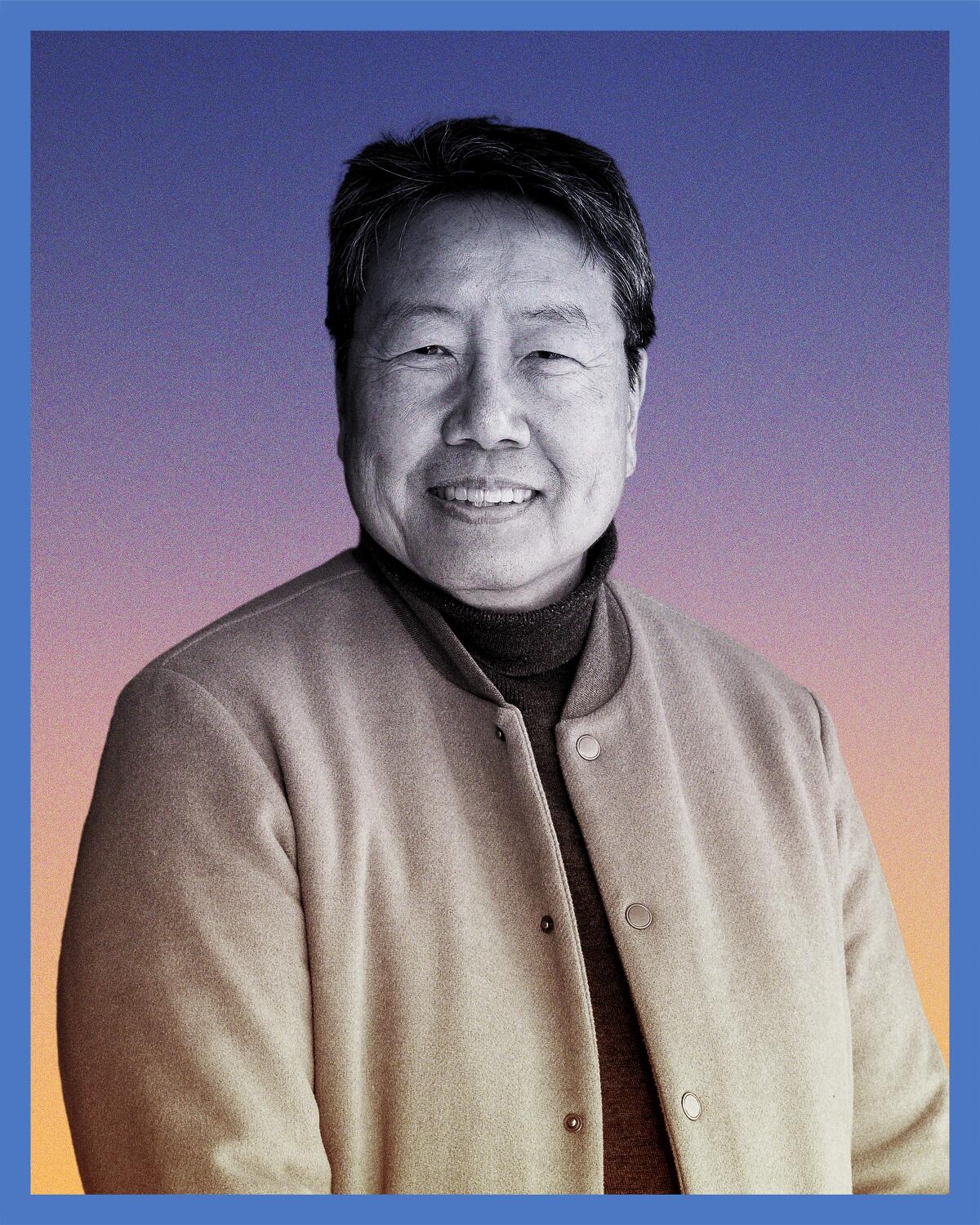

Chief Executive of Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California, a legal and civil rights organization

As a Korean and Asian American who grew up in L.A. and lived through the 1992 uprising (known as Saigu in Korean), there’s no doubt there were deep racial tensions. And racial tensions continue to be a problem in L.A. today, as we saw all too well when the City Council audio leaks came out last year. That being said, I think L.A. is still one of the most amazing places to live as a person of color. This is a majority minority town. Latinos make up about 50% of the population and Asian Pacific Islanders are the fastest growing racial group. L.A. embraces historically marginalized communities, whether you’re a person of color, an immigrant or LGBTQ+.

Things have vastly improved since 30 years ago, when Korean Americans were still a fairly new immigrant community, struggling with language and cultural barriers. Today, a whole generation of us were raised in the U.S. and have successfully navigated systems. We’ve had City Council members like David Ryu and now John Lee who’ve entered positions of power and leadership and speak up for our community.

And we’re not just accepted for being Korean, our culture is now celebrated. L.A. loves its Korean BBQ and fried chicken. Roy Choi’s Kogi Truck sparked a food truck revolution across the US. Koreatown is a 24/7 mecca for food and nightlife. This is a far cry from how Korean culture was viewed in the early 90s, when I wouldn’t be caught dead eating kimchi in front of non-Koreans.

It’s not perfect living in L.A. I still feel like Korean and other Asian Americans get overlooked — we’re not as civically engaged, nor are there enough of us in positions of political power. And I hate all the multimillion-dollar homes when we have tens of thousands of unhoused Los Angelenos. But when I think I’ve had enough — of the traffic, skyrocketing living costs and other issues — I’m drawn back by our diversity, progressive values, and being surrounded by so many Korean and Asian Americans. It’s far from hell; this is home.

Founder of Homeboy Industries, a gang-intervention, rehabilitation and re-entry program

Anybody who suggests we haven’t made progress isn’t paying attention. Because there is no comparison. When the Time article was written, things were really horrible in terms of policing. Now, police are meant to serve as guardians as opposed to warriors. That article partly focused on gangs, but gangs would not be on anybody’s top three list of biggest concerns. Now they would say homelessness, but that wasn’t even on the radar then.

In communities like mine in Boyle Heights, we still feel the impact of gang violence, but not like 1993, when the Time article appeared. 1992 had the highest number of gang-related homicides, and since then it has been cut in half. On the gang front, the collective imagination changed. Homeboy Industries became an exit ramp from gang life. My hope is that we now have a broader sense of trauma, mental health, poverty and despair — all the things that impact behavior. In the story, there were mentions of gang conflicts and truces. But gang violence is about something else — it’s not about conflict. It is certainly not about bad people doing bad things. It is the language of people who are stuck in despair.

One of Homeboy Industries’ social enterprises, Homeboy Tortillas, was included in the Time article, I suppose, because we had started to get support that we hadn’t gotten previously. Back then, Homeboy Industries had three social enterprises — now we have 10 more, along with about 500 employees. May we never again repeat the decade of death, which was 1988 to 1998.

President and chief executive of the Los Angeles Conservancy, a nonprofit focused on historic preservation

When I first joined the L.A. Conservancy in 1992, the Herald Examiner Building on Broadway was one of many buildings threatened with demolition to make way for a parking lot. The Conservancy assembled a coalition to advocate for its preservation, resulting in having the demolition put on hold. The Herald Examiner building was recently restored to become the Los Angeles flagship for Arizona State University.

One of our toughest battles was the fight to save St. Vibiana Cathedral in 1996. To preserve one of L.A.’s most important historic landmarks, we had to go up against the city power structure —including then-Mayor Richard Riordan and Cardinal Roger Mahony. The cathedral was ultimately saved through several lawsuits and the offer of a different downtown location.

For more than thirty years, we have worked hard to build a preservation ethic in Los Angeles, so that historic buildings are perceived as resources that preserve our history, foster our identity and help meet community needs, such as housing. Only a few years after Vibiana, the Adaptive Reuse Ordinance of 1999 was a major milestone for the city that has since resulted in 14,000 units of housing created in historic downtown buildings.

It’s incredible to see Angelenos preserving the historic places they love; the places that tell their stories. The cliche that L.A. doesn’t care about its history has never been further from the truth than today.

President and chief executive of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce

Thirty years ago, I was working at Rebuild L.A., the organization that came together after the 1992 uprising to help aid the city’s restoration. The effort was led by business, civic, and philanthropic leaders. My role was to help support efforts to bring business into South Los Angeles to be a part of the recovery. That moment in time just showed the determination of Angelenos to engage diverse voices to come together to address challenges. I remember thinking, the residents of Los Angeles are resilient and care deeply about their city and they will not let this city fail.

Over the last 30 years, our business community has evolved. The aerospace industry, for example, had been a key economic driver and job creator; today, our economy boasts diverse industries and is the epicenter of innovation and creativity.

The residents of Los Angeles are resilient and care deeply about their city and they will not let this city fail.

— Maria S. Salinas

Small, diverse businesses are one of Los Angeles’ greatest assets, and their ingenuity and resilience ushers our economy forward. I am very optimistic about the future for the L.A. region. Business leaders can help solve problems today just like they did 30 years ago.

Director for labor and community partnerships at the UCLA Labor Center

Of all the major cities in the U.S., L.A. has the largest gap between the rich and the poor. And yet, at the same time, we have seen tremendous advances in working-class communities that have organized and created change over the last 30 years.

Historically, Los Angeles was never a union-friendly city. But it’s been changing. A little more than 30 years ago, the SEIU launched the “Justice for Janitors” campaign, which demonstrated to unions across the country the potential and power of organizing the new Latino immigrant workforce. And after a 10-year campaign, 74,000 Los Angeles home-care workers successfully unionized in 1999.

Thirty years of organizing set the foundation for the “Hot Labor Summer.” This year, we witnessed the power of worker solidarity embraced by hotel workers, actors, writers, city employees, university workers, teachers, and school employees.

During the pandemic, massive economic and racial inequities were laid bare. We saw workers on the one hand being celebrated as “essential” and yet on the other hand treated as if they were disposable. At the same time, the suffering and death was most pronounced in working-class communities of color. This set the foundation for the tremendous upsurge in workers mobilizing, organizing and demanding change. The national labor movement has benefited from the revitalization of L.A.’s labor movement — especially with regard to the emergence of more women, young people, immigrants and workers of color joining unions.

Essayist and author of books including the memoirs “Excavation: A Memoir” and “Hollywood Notebook”

In 1993 I was finishing community college at Los Angeles Valley College, and I had just taken classes like Chicano studies, political science and sociology. One of my professors was a Marxist and another a Socialist. It made me much more politically conscious, and really angry about what I was witnessing in L.A. Hell was Rodney King being beaten and watching police behave like sanctioned gangs.

All cities encompass both heaven and hell.

— Wendy C. Ortiz

That year I moved to Olympia, Washington, to finish my degree. In 2001, I moved back to L.A. — to a part of the city I’d never lived in before, East Hollywood.

Coming back to L.A. was a new shock. I hadn’t realized when I moved back here: Oh, I have to drive 15 minutes to find a parking spot every single time I move my car. Rent was at least three times more than what I paid in Olympia. I expect this in many major metropolitan cities. Still, I loved it. This is where my family is, where I’m from.

All cities encompass both heaven and hell. I don’t know where my mom picked this up, but she once said hell is where some of the most interesting people are. And I agree. There are going to be more interesting characters in hell than in heaven. And Los Angeles is the hell I’ve chosen.

Host of KCRW’s “Good Food,” chef and owner of Angeli Caffe, which operated from 1984 to 2012

Thirty years ago, most restaurant food was about a national culinary tradition, usually French or Italian. Now it’s more common for food to be an expression of identity. Clearly, the change from then to now is a story of greater inclusion and diversity, which equals more deliciousness.

This city’s culinary landscape grew up in Jonathan Gold’s image. He opened us up to the idea that there is more to eat out there, and that we should get out of our comfort zones to go eat it. He told those stories. Now people of those communities are rightly telling their own stories.

And of course the way we consume those stories has changed, too. An individual on TikTok can have as much impact on what people eat or where they dine as a critic may have had 30 years ago. That is a monumental change. Discovery is a good thing. When I think about all the work Jonathan did — he was out front, like a scout, pointing out the landmarks. But we have to do the work of sitting down to eat ourselves.

Former president of the Los Angeles Police Commission and managing partner of real estate company Soboroff Partners

L.A. may not be at the footsteps of heaven, but we are a long way from hell. In 2013 — the year Mayor Garcetti asked me to be LAPD Commission president — the Police Department was emerging from 12 years of a federal consent decree. It had required a transformational change from militaristic policing to a community-based strategy stressing de-escalation, community safety partnerships, and the hiring of more women on a more diverse force. Before taking the job, I called 26 leaders including Connie Rice and John Mack for advice. Their words gave me confidence. One memorable result: body cameras.

Around this time, Rialto had put body cameras on a few officers with positive effect on both sides of the lens. L.A. didn’t have the budget to start such a program for its much larger force, so we decided to approach private donors for $1.3 million to test 700 cameras. With similar results to Rialto, the City Council would hopefully vote to equip 8,000 officers.

Soon after the pilot program launched, the mayor told me that he spoke with President Obama and the Feds were granting another $1 million. It took months — versus years — to implement. The results are remarkable: a decline in complaints and incidents. Body cameras are the national norm. Chiefs Bill Bratton, Charlie Beck and Michel Moore and the Los Angeles Police Protective League embraced proactive, progressive public-private partnerships like this.

L.A. currently has hundreds of service providers like Big Brothers Big Sisters of Greater Los Angeles and Homeboy Industries, but they all need additional funding to combat new drug and homeless issues, and increasingly brazen and sophisticated gangs. Public-private and community-safety partnerships are heavenly!

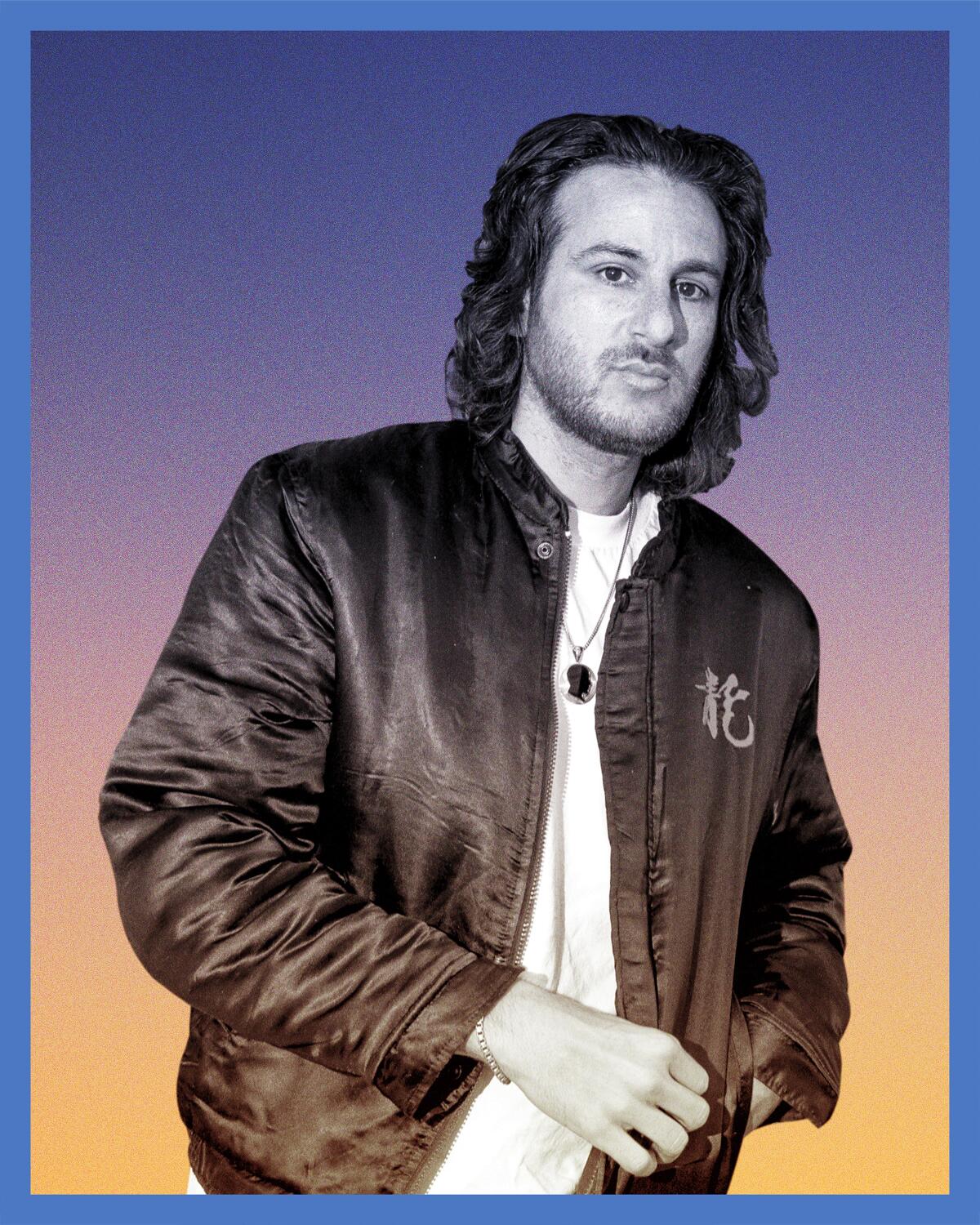

Music journalist and founder of the POW music website, author of the forthcoming book “Waiting for Britney Spears”

Los Angeles loves and lives off extremes. After all, they supply the best drama. Despite their differences, both Carl Laemmle and N.W.A intimately understood the art of storytelling. That’s probably why Universal Pictures released one of the most successful biopics ever, “Straight Outta Compton,” about the do-or-die vicissitudes of the world’s most dangerous group. If gangsta rap is L.A.’s most famous musical export of the last three decades, it has come with a Mephistophelian curse.

Hell is a hallucinatory figment, but the streets of Los Angeles can get uncomfortably hot too.

— Jeff Weiss

Tragedy has long shrouded the sonic lore of the city: whether it was the murder of Tupac, the city’s adopted patron saint, or the allegedly retributive slaying of The Notorious B.I.G. outside of the Petersen Automotive Museum. We possess a storied history haunted with “what ifs?” What if Eazy-E hadn’t died of AIDS? What if Suge Knight and Death Row had pulled back from the darkness? What if Nipsey Hussle hadn’t been killed? Or the Texas penitentiary system hadn’t stolen five years of 03 Greedo’s prime? What if they hadn’t assassinated Drakeo the Ruler, the Cold Devil himself, in the shadow of the Memorial Coliseum. Hell is a hallucinatory figment, but the streets of Los Angeles can get uncomfortably hot too.

Veteran bilingual journalist and managing editor of Boyle Heights Beat since 2019

Being optimistic, I say that things are getting better for Latino media in L.A. But I don’t think we’ve gotten to the point where we can stop fighting.

Latinos make up about 50% of the population in L.A., but the percentage of Latino journalists at major publications is noticeably smaller. And there’s a segment of that Latino population not being served well — Spanish-language speakers. La Opinión, where I spent 22 years, is nowhere near what it was in the ’90s in terms of covering the city. These days, many issues are not being covered, and surveys show that Spanish-speaking Latinos get their information from social media and television. I lament the state of affairs, absolutely — but I think Latinos will continue to grow in the media.

This community is not being adequately covered by the media — and I have kept that fresh in my mind as Boyle Heights Beat has grown. Our mission, to cover local news, is an important part of journalism today.

Founder of architecture and technology website BLDGBLOG and author of the nonfiction book “A Burglar’s Guide to the City”

It’s rare an entire city goes to hell all at once, even in times of war or natural disaster. The destructive effects of a riot, of a terrorist attack, of wildfires and earthquakes, remain localized and particular; many of us are dragged down while most of us escape. There is a standing wave of vulnerability and salvation that churns beneath the surface of Los Angeles, the great bipolar metropolis of the American West. Extremes here agitate within sight of one another, often across a single property line, sometimes simply in the difference between what we have today and what we’re left with tomorrow.

Yet solidarity is a difficult prospect in hell; we can’t unionize against suffering, divest from betrayal, or boycott pain. The appeal of Los Angeles is, instead, an otherworldly one. Rising and falling, shaking us off — or trying — L.A. promises unrest. The ground will shake; burning winds will descend from the mountains; predators will seek the weak; but forces we rarely control are the whole point of living here, of being in contact with something larger than ourselves, awaking amidst cycles of risk and recovery through which we all, individually, are continually transformed.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.