Why thousands of L.A. students are showing up for school during winter vacation

Zenzhel de Guzman wasn’t too sure what to expect for her son during the winter academy — Los Angeles Unified’s three days of optional school over the long holiday break. Her first-grade son was attending a different campus. She was unsure how the time would be structured. But at least she would not have to worry about child care for a while.

Added bonus? She hoped he’d be able to learn a bit more about science — his favorite subject — and perhaps get some extra help with reading.

“I think that will be good for him,” she said. “And he’ll be meeting different kids.”

LAUSD’s winter academy provided both an opportunity for older students to catch up on work and offered relief to parents struggling to find child care for the youngest students during the district’s three-week-long break. More than 68,000 of the district’s 419,749 students had registered for the program across 350 of the district’s campuses, but attendance has not yet been released.

As preschools and school districts close for the holidays, working parents are scrambling to find child care and provide additional meals for kids at home.

This is the second year the district is offering the additional days of academic support in an effort to fill gaps in learning exacerbated by the pandemic. Across the district, nearly 70% of students are below grade level in math and nearly 60% in English.

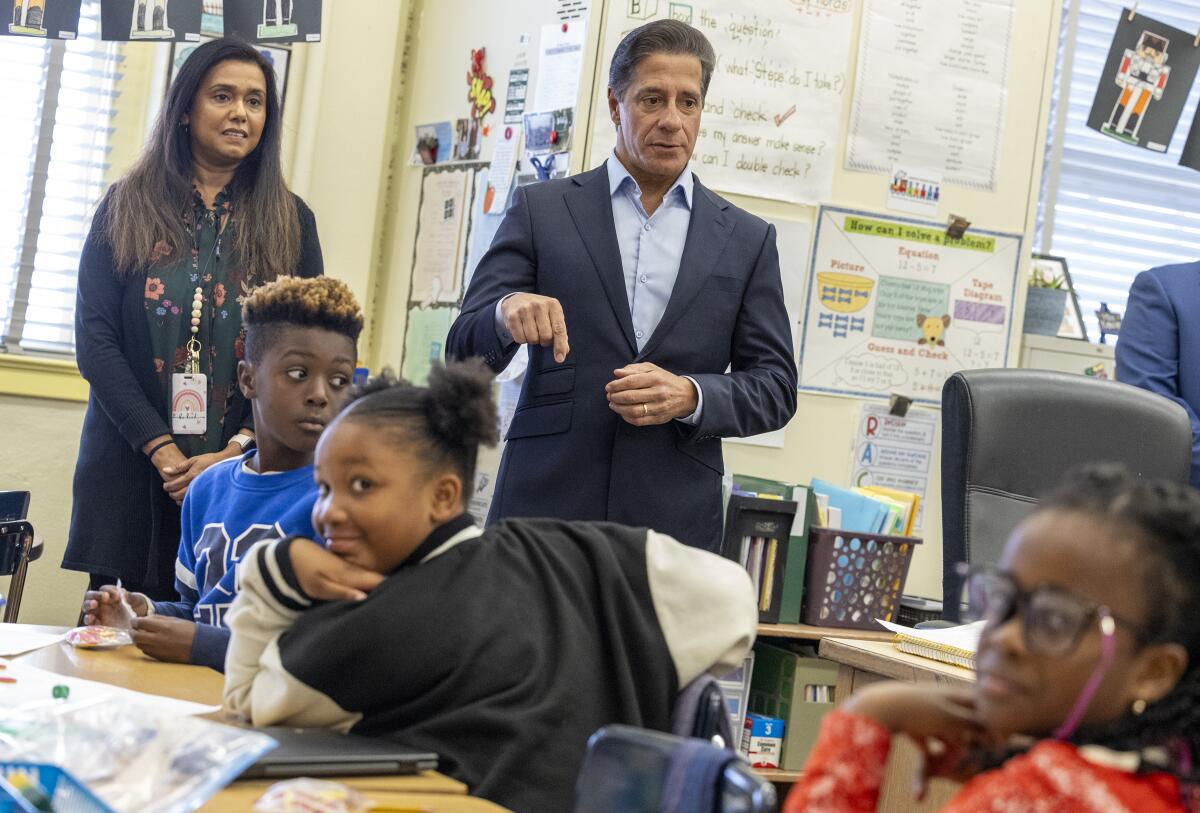

“Right now in our district, our teachers are working hard, our leaders and supportive staff are working hard, our students are attending school,” LAUSD Supt. Alberto M. Carvalho said at a news conference Monday. “There is positive momentum on the horizon.”

Last year the teacher’s union rejected a plan to offer optional learning days by extending the school year. Instead they were tucked into winter and spring breaks with a mixed reception and low attendance of 36,486 students over two days in December and approximately 33,000 in April.

Carvalho is committed to the program, and the district plans to offer it during spring break and intends to repeat it in the 2024-25 school year, despite the end of pandemic relief funding. Carvalho said he expects other grants, such as Title I, to supplement the cost of the programming.

LAUSD initially disclosed that last year’s two optional winter learning days cost the district $36 million, according to a January school board presentation. Carvalho later revised the costs to $11.6 million. The district declined to provide backup documentation for the changed figures.

The district on Tuesday declined to release attendance numbers as well as the estimated cost for this year’s learning days.

Similar to last year, middle and high school students can take the days to finish missing assignments and do additional work to boost their grades. Some students were also pulled aside for one-on-one help. This year, students will take before and after assessments to evaluate the impact of the program, Carvalho said.

“Not only are we teaching during these three days of winter academy, kids are getting nutrition, they’re getting social emotional support, and they are getting transportation. They are getting everything they need,” Carvalho said. Although LAUSD’s three-week break has broad support, there are many working parents who struggle to find child care and say the loss of school meals is a hardship.

At Carson Street Elementary in Carson Monday, 250 students were scattered across classrooms for the winter academy. Ashida Ramzan led 15 third-graders through a math activity. Using dice to roll out equations, they practiced multiplication. Later, they would take their initial assessment and work a bit on reading and writing, according to Monica Romero Martinez, a teacher’s assistant at a district adult school who provided help to those struggling with the assignments.

California law restricts preschools from expelling kids, yet an increase in behavioral problems since the pandemic is proving a big challenge for teachers.

Extra support is something Shardesia Langford, a mother of a first- and fourth-grader, has always been eager to take advantage of — including winter academy and tutoring.

“They get the chance to catch up on anything they may have missed or anything in areas that they’re struggling in,” Langford said about the benefits of the extra three days in school. “They get extra help.”

For Christal Campbell’s third-grade daughter Chloe, who attends Catskill Avenue Elementary, the extra days weren’t so much about getting extra academic help but about exploring science. She was excited to try out a new school for a few days while not having to worry about coordinating for a grandparent or another family member to help care for her.

“We still have to work,” Campbell said about the three-week break. “When I went to school, it was only two weeks. Now, they get like three weeks. They get a lot more time off, so it helps out.”

At the middle and high school level, the work was more individualized. The 115 students attending the winter academy at Hollenbeck Middle School in Boyle Heights primarily worked on missing assignments and additional work assigned by their teachers to help boost their grades as the semester ended.

That was the case for eighth-grader Jessica Ramirez, who was working on improving her D in math and trying to build a better foundation for the subject this school year. She was able to get some one-on-one help in the classroom while she worked on solving equations, which she said is helping her better understand the concepts.

“I really want to do better before high school,” Jessica said. English and history are next on her list as she looks toward the next few days, she added.

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.