D.A. drops poker-chip theft case against deputy after witness cites fear of deputy gangs

The district attorney’s office has decided not to prosecute an East L.A. deputy accused of stealing $500 in poker chips during a traffic stop after the driver who sparked the investigation said he feared retaliation from “deputy gangs.”

When he was first questioned about the missing chips, prosecutors said, Deputy Braulio Robledo denied having pulled over the professional poker player at all. It was only after a sergeant reviewed surveillance video and the patrol cruiser’s logs that authorities figured out who’d made the stop, according to a memo from the district attorney’s office.

On Friday, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department said Robledo been put on administrative leave but declined to explain what that entailed, claiming that it was legally barred from saying whether he was still receiving pay.

The case is still the subject of an internal investigation, the department said.

“The Sheriff’s Department holds each of its members to the highest standards and expects them to act with integrity and professionalism,” the department said. “Any employee that violates the public’s trust and engages in misconduct will be investigated and held accountable.”

Robledo could not be reached for comment.

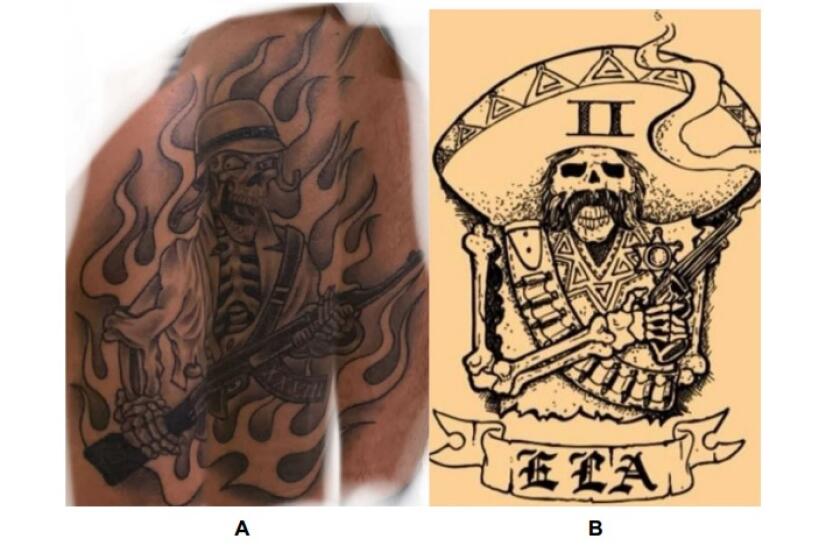

For decades, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has been plagued by allegations of secretive deputy gangs operating within its ranks, running roughshod over certain stations and promoting a culture of violence. One of the most well-known of those groups allegedly operates out of the East L.A. station, and is commonly known as the Banditos.

In a 42-page ruling that is sure to be contentious, a civil court judge effectively blocked the county watchdog from thoroughly investigating deputy gangs that operate within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Previously, several lawsuits — some still ongoing — have accused Robledo of being a member or prospective member of the group. It’s not clear whether he has ever formally denied that allegation, and his attorneys did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The department did not say Friday whether Robledo had been questioned about alleged gang membership, instead offering a statement reiterating the sheriff’s commitment to eradicating deputy gangs.

Sean Kennedy, who has investigated deputy gangs as the chair of the Civilian Oversight Commission, criticized the district attorney’s decision not to pursue the case, saying the appropriate response would have been to “to thoroughly investigate” the deputy’s possible gang affiliations.

“Instead, the D.A. blames the victim for being noncooperative and declines to prosecute,” Kennedy said. “This approach enables the LASD leadership to keep turning a blind eye to the problem of deputy gangs in the department.”

The district attorney’s office pushed back, saying nothing written in the 17-page memo released in August through a public records request should be taken as blaming the witness.

According to the memo, on the morning of Jan. 2, 2020, a professional gambler — whose name was redacted — left the Commerce Casino around 3 a.m. and was immediately pulled over for an expired registration. The deputy patted the man down for weapons, put him in the back of his patrol cruiser and searched his vehicle before letting him go with a warning.

Afterward, the man said, he realized that $500 in white Commerce Casino poker chips had gone missing from his backpack, so he called the East L.A. sheriff’s station to report the incident. The sergeant who fielded the call said he’d look into it, and when he asked the three deputies assigned to the area that night, two of them messaged back saying that they hadn’t made the stop. According to the memo, the third deputy — Robledo — did not respond. Around 6 a.m., the sergeant again asked Robledo whether he’d pulled over the poker player. This time, the memo said, Robledo denied it.

But another sergeant reviewed surveillance footage from nearby cameras, which showed that the deputy who conducted the stop had been driving an SUV. Department records showed Robledo was the only deputy driving an SUV in the area that night, the memo said.

In an interview a few days later at the East L.A. station, the poker player explained how much money he’d had in cash and how much in poker chips, and suggested investigators could review footage from the casino to confirm how much he’d cashed out that night.

When investigators reached out to the poker player a few weeks later to follow up, he sent them an email saying he did not want to pursue the case, citing his fear of deputy gangs — specifically, one he called “Los Banditos.”

According to the memo, he told investigators that he “would be putting his life in danger” if he cooperated. For more than a year, investigators continued following up with him, but the man ignored their calls. Eventually, they lost track of him and by January 2022 decided they were out of options.

When prosecutors reviewed the case, they said the video surveillance appeared to show the player left the casino that night with a different number of poker chips than he said, and that the missing amount might have totaled $300 instead of $500. Prosecutors also suggested the poker player could have simply miscounted his earnings. Either way, they said, without a cooperating witness it was impossible to prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that Robledo had robbed anyone that night.

Prohibiting sheriff’s deputies from joining gangs raises 1st Amendment concerns. But the arguments for doing it are overwhelming.

This is not the first time Robledo’s name has been at the center of a criminal investigation. Records show the district attorney’s office previously investigated him in connection with a 2019 on-duty incident involving three women, one of whom accused Robledo of asking her to touch his penis.

The woman did not say he forced or threatened her, prosecutors said, and they declined to pursue charges.

“Although the behavior is unbecoming of a police officer, the facts in this situation do not lead to the conclusion that Robledo’s actions were unlawful,” prosecutors wrote.

“Although Robledo was in full uniform, which by its nature authoritative,” prosecutors continued, “that fact alone is insufficient to prove the requisite force was used.”

Before that, Robledo was one of the deputies allegedly present during the now-infamous middle-of-the-night altercation that occurred after a station party at the Kennedy Hall event space in 2018. Just before 4 a.m., a group of older deputies — later alleged in lawsuits and reports to be members of the deputy gang known as the Banditos — got into a fight with several younger deputies. Two of the younger men were knocked unconscious and later hospitalized. Though Robledo wasn’t accused of taking part, another deputy told investigators that Robledo had helped instigate it.

Ultimately, prosecutors declined to press charges against any of the deputies involved, though the case spawned several investigations and lawsuits, one of which named Robledo as a defendant and two of which described him as being a member or prospective member of the Banditos.

In 2021, he was named in another lawsuit — this one over alleged racial discrimination at the East L.A. station — which also described him as a member of the gang. That case is still pending in state court.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.